The site was a full on media blast, with endorsements by consumer brands everywhere, and British cultural icons of the time prevalent – Sega held a star-studded opening day with scores of celebrities, like Robbie Williams, and by the time Pepsi’s “GeneratioNext” ad campaign rolled around, the mainstream pop music starlets of the moment, the Spice Girls, could be heard belting out their song Move Over in the main atrium every other minute.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jqgz7hDxR-s

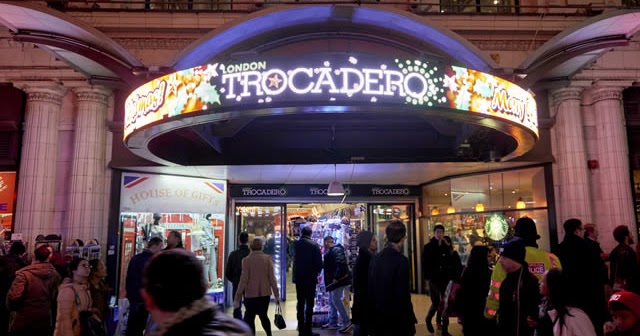

Back to Sega World itself. Before zipping up the two rocket escalators, visitors would walk through the Trocadero’s shopping arcade entrance way. Immediately, Sega’s presence could be felt with two Sonic statues – the first placed outside, a golden one above a circular LED sign advertising the centre, and another by the entry point of the first escalator.

In total, there were 6 floors to the place, linked together and accessible through a further series of escalators and travelators, all either criss-crossing through floors or at the left and right sides of the very top of the Trocadero’s atrium.

The first floor was the reception, where game tokens and later ride tickets could be purchased, and photo opportunities could be taken with another Sonic statue, clearly the centrepiece of the floor. A video wall, running a promo video informing visitors of the floors and attractions, ran behind this. Sega Saturn console setups could also be found here, often showcasing new releases including the likes of NiGHTS Into Dreams.

Just below the reception was then the first proper floor, Combat Zone, which had over 70 action games; mainly shooters, light gun games, and fighting games, like Virtua Cop 2, Virtual ON: Cyber Troopers, Fighting Vipers, and Virtua Fighter 3 – VF3 in particular had its UK launch at Sega World, having only just been put out in Japan weeks beforehand.

The Combat Zone also featured the first ride, Beast In Darkness. This was one of the only attractions to not have some sort of VR or 3D graphical feature, instead being more of a glorified ghost train/haunted house type deal, with sensors, surround sound, and the occasional live actor walking around to simulate the ‘beast’ lurking around you.

Next was The Race Track- this floor had over 70 racing games, and was arguably one of the more impressive floors of the place. Upper walls featured replicas of cars sticking out of them; highlights of its game selection included back to back 8 player deluxe setups of Manx TT Superbikes and Daytona USA. In addition to its cameras outputting video of racers to the screens above the cab marquees, the Daytona even had running commentary provided by an employee.

Many other linked multiplayer racing games were also situated here, including Scud Race, Sega Rally Championship, Sega Touring Car Championship, Le Mans 24, Harley Davidson & L.A. Riders, and Motor Raid.

Also notable here was an impressive Sonic mural, and the very F1 car that Damon Hill once drove in the 1993 Formula One European Grand Prix.

The Race Track’s main attraction was Aqua Planet, also known as Aqua Nova at other Sega World and Joypolis locations. In it, riders would don a pair of 3D glasses and be transported to an undersea world which fell to decay at the hands (or tentacles, rather) of a giant squid monster. The main objective was to kill said squid, with three different endings achievable depending on how well teams did in doing so.

The 3rd floor was known as The Flight Deck, which featured 20 different flying games, including Sky Target, Wing War and a couple of the previously alluded to R360 simulators. An elusive Sega Net Merc VR machine could also be found here; a mere 70 units of it were supposedly produced due to the short supply of Model 1 arcade boards, with very few making it out of Japan.

Even more impressive was the Harrier Jump Jet hanging from the ceiling, which was lowered through the Trocadero’s ceiling by a crane in a press event.

This floor’s ride was VR-1 Space Mission, one of the premier simulators of the venue. This ride combined VR, hydraulics and sensors to provide a fully immersive VR experience, in which you would aboard a spaceship to ‘deliver vital information to the planet Basco’, destroying any enemy ships or debris in the way.

Sega World’s biggest floor was The Carnival – a floor dedicated to ticket redemption machines, and more family-orientated games, with bright, garish colours everywhere. As such, there was a prize desk, where exclusive merchandise could be won, as well as Sega’s consoles and games themselves.

While the UFO Catchers and ticket games were this floor’s main draw, there was also a section on this floor called ‘Segakids’, with outlandish Sonic themed decor, including palm trees and gold rings painted on the walls, a McDonalds outlet shaped like a box of fries, and a childrens play area next to it.

This floor also had 3 rides. The first was Power Sled, a bobsled simulator that used four moving replicas of sleds and large projection screens to best simulate the feeling of flying down a sloped sled track.

A later addition to the park in 1998, this was at a few other Sega Worlds, and was also not limited to them – a few turned up at non-affiliated amusement centres in America and Japan, though this was the only known one in the UK.

The 2nd was House Of Grandish, another subsequent addition from 1997. Grandish was not too dissimilar to Beast In Darkness, in that it was another haunted house type attraction, with the added difference of your heart rate being monitored throughout it and given to you on a card by the exit.

The 3rd attraction and longest standing one was Ghost Hunt, an interactive ghost train. Riders would get in two seater pods, using transparent projection screens to overlay 3D monsters onto the real life background of a haunted mansion. These monsters could then be shot at with gun yokes; players were graded on how well they did by the end of the ride.

The final floor was The Sports Arena, which had 90 sports themed games. Among them were Alpine Racer, Wave Runner, and Sega Bass Fishing. A huge surfing Sonic statue could be found in the centre of the floor, and not only that, his two arcade games were situated here- SegaSonic Arcade, and Sonic The Fighters.

This floor appears to have been used most often for corporate parties, as shown in the videos below.

The floor had 2 rides – AS-1, one of the first of the line-up to be developed, offered the main technological thrills. AS-1 units had much in common with a normal motion simulator, already flooding theme parks all over the world, only better – it could hold more people, and was interactive. Sega World had two shuttles, one running Michael Jackson’s Scramble Training, the other, Megaopolis: Tokyo City Battle.

Both saw you take some level of control of the game with a flight stick-type controller after brief introductions that utilised the technology, and played different endings depending on how well you did during the game.

The second ride was Mad Bazooka, a sort of bumper cars ride with an added twist. On the floor were little foam balls that your car could pick up and shoot out, aiming at a target on your opponents. Cars could only take so many hits before. This attraction was seemingly removed at some point during 1998, making no appearances in any leaflets or promotional material afterwards.

Also on the floor was the Sega Store, a prerequisite of any true theme park or tourist attraction. Sold in it was of course all kinds of merchandise, as well as Sega Saturn games and consoles.

With a strong lineup of hundreds of arcade games, several rides, and impressive theming, it sounded like nothing could go wrong. Surely Sega World would remain successful for years to come. But, a literally costly decision was made right from the start, the entrance fee, at £12 for adults and £9 for children.

Visitors had to use their own money on the arcade games, sometimes costing up to £3 – not only that, but the expensive rides could only hold so many people at a time. A PR disaster was inevitable for Sega World, and on its grand opening day, in which numerous celebrities and members of the press visited, some rides had hour long queues, even with not many people in attendance. Some attractions could only take in 40 people every 60 minutes. They were simply not designed to sustain and power through the footfall that a Central London location could bring, a massive oversight on Sega’s part.

Needless to say, newspapers and critics who reviewed the place were not impressed, criticising the cost of most everything in the place as well as the long wait times for so little in return, and so began a dogpile of bashing in the press. Sega World was not a high-tech theme park to many- it was a tacky tourist attraction with no heart or character put into it.

The Daily Telegraph described the park as “little short of a disgrace” and a “joyless tourist trap”. Cosmo Landesman of the Sunday Times felt that it was overall “very tacky”. John Tribe of The Times reported the rides to be a “glitzy con-trick”. Perhaps the biggest kicker for Sega was the immediate discouragement of Nick Leslau, the Burford Group executive who helped make Sega World a reality:

“Sega could not deliver what they said they’d deliver. It looked amazing, but their rides were not capable of delivering the number of people they needed to deliver to support the operation. People were queuing for ages. It was a question of over-anticipation and under-delivery.”

Sega quickly realised the criticisms, and in response put all the arcade machines on free play, as well as making moves to redesign the ride queuing systems. Despite getting the word out through important outlets for gamers, like Channel 4’s Gamesmaster series and various magazines, the move fell on deaf ears for the general public and the mainstream media.

They then took the entrance fee down to £2, bringing the games back off freeplay and charging customers redeemable tickets for the rides of their choice – cheaper, and in theory beneficial for all involved. While visitor numbers improved slightly, it too did nothing to dispel the notion on the site, and although few knew it at that point, Sega World’s fate was essentially already sealed.

Confusion also reigned supreme on how the arcade machines would be charged for – management went back and forth between payment methods involving standard currency, dedicated game cards, and special tokens, some of which sourced from other Sega venues in the UK. In the midst of this, profits that should’ve made from them were seemingly lost.

Scrubbing his hands of what he already knew was a failed venture, Nick Leslau quit his managerial role at the centre, giving way to John Conlon and Nick Tamblyn, previously of the First Leisure group. The new higher-ups immediately resented Sega – Conlon was heard to remark he ‘wanted to get rid of Sega’, the very day after he joined the company on the 2nd of September 1997.

And while arcade gaming, at least in the sense of the health of dedicated player scenes, was about to enter its best state in years, it still wasn’t what it once was. Global losses were abundant on the corporate side of things around this time period, with the largest casualty being once-heavyweights SNK filing for bankruptcy in 2001, despite Playmore picking up its pieces.

Over in Japan, several Joypolis venues were closed as part of a restructuring, and eventually Namco’s Wonder Eggs parks were also shuttered. Sega’s GameWorks venture in North America had scaled back its ambitions, scrapping plans for hundreds of new locations. Sega World Sydney in Australia closed permanently too – little could be salvaged from the brief time that ambition was high in the amusement industry.

Embodying the era was a quote from one of the scene’s most infamous players, Jason Ho, that has since almost passed down into legend:

“It’s a social thing.”

However, despite the revitalisation of Funland, Sega’s pulling out triggered a knock on effect that would further the decline of the Troc as a popular tourist attraction. The trusted brand recognition, even if smaller by the time of 1999, had pulling power for the Trocadero, and without it, the place was considered as slightly less of a noteworthy attraction in the minds of advertisers.

Pepsi were the next to go in early 2000, after another IMAX opened elsewhere in the centre of London. While the IMAX and sponsorship branding around the centre was removed immediately, the Pepsi Max Drop stayed for another few years, rechristened to ‘London’s Scream Ride’.

The Madame Tussauds branch in the basement followed suit in 2001, and some of the more upmarket shops and former VR experiences (Emaginator, Virtual World) were hastily replaced by shops and snack bars upon their closures. More worryingly, crime was on the rise too, on either side of the centre – corporate and consumer. The Trocadero’s reputation was already declining, but it still wasn’t as bad as it was to soon end up being. Funland’s success was not to last.

Declining Trocadero (2002-2011)

In September 2002, the upper floors of Funland (the top 6 or so floors of the Trocadero) were completely shut off to the public by management. The lights dimmed, the media blast of the atrium died, and the Y2K heyday of the place was now effectively over.

One of the reasons for this was the increased dominance of consoles, which had now properly caught up to arcades in graphical standards. But the main one was the huge investment Family Leisure had to continually make in ensuring the place would make a profit.

Management weren’t used to running such a large centre as this, and often had issues with sufficiently staffing the numerous floors, leading to issues with crime and antisocial behaviour. Something had to give, and it did.

The second rocket escalator was effectively rendered useless by this move, and was blocked off to the public – taking out all of the upstairs rides and arcade machines with it. Looking to minimise costs alongside Funland, Trocadero management decided to remove the video wall at some point around this time, and lighting features plus décor installed in the 1996 revamp was stripped.

What was once the Pepsi Max Drop was also removed, and relocated to the “Funland” fairground on Hayling Island (no relation), as well as the other rides that were installed on the upper floors.

However, the remaining 2 or so levels of Funland were still stocked full of games, and throughout its final years an effort was still made to get the newest releases.

Alongside Casino Leisure elsewhere in London, which catered better for traditional games like shoot ’em ups and fighters, the Troc was certainly still considered one of the premier arcades in the country, especially with numerous others going into worse decline than Funland itself.

Location tests for Dance Dance Revolution X and Jubeat were held by Konami, and it was the only arcade in the UK to regularly get the newest instalments in the Korean Pump It Up dance game series – most places having abandoned it after the early 2000’s due to its difference in style and music to the standard DDR.

Other imports and rarities like Street Fighter IV, Virtua Fighter 5, and Initial D Arcade Stage 4 meant that Funland was still well respected by most gamers. As a result, the place stayed open from the steady support and tourists who still bothered to come, despite it now looking rather rough around the edges – indeed, traces of the upper floors were never removed, with visible boarded up floors directly above the open ones, an obvious mark left by a removed McDonalds sign, and the 2nd rocket escalator almost comically being blocked off by a drink vending machine.

In 2005, a company called Criterion Capital owned by property developer Asif Aziz bought the Trocadero, and started plans to yet again gut out the interior of the Trocadero for a 500 room pod hotel. This didn’t spell good news for Funland and the rest of the complex’s tenants as a whole.

Criterion also allowed what were pretty much market stalls to trade in the atrium. This gave the whole place an odd feel compared to what it was before, with most of the stalls selling questionable, tacky goods. As the neon on the escalators burnt out, and remaining décor installed in 1996 or even earlier started to decay, the Trocadero sank even lower yet.

Meanwhile, above the 2 operating floors of Funland, building work was being carried out on the decaying floors of Sega World, removing the remnants of the branding after a health and safety check deemed them highly dangerous due to the sheer amount of dust and asbestos left exposed. The only time the upper floors were used during this time were for the odd private party – the Gumball 3000 Rally Championship 2007 launch party was held there, and pictures of it can be found in this album on Flickr.

But also, a few select people went up the closed off escalator and saw the remains of Funland and Sega World. Thanks to @Ricky_Earl on Twitter, who very kindly sent the pictures taken during research of this blog post, we can now see what was left.

(up the closed off ‘rocket’ escalator…)

(lots and lots of dust!)

(once the entrance, now a torn down and empty floor of nothing)

(a closer look)

(some remaining decor on the walls of the combat zone floor, is recognisable from the videos)

(down a derelict stair way…)

(…to what could be the ‘race track’ floor. this picture somewhat matches up with a part from one of the videos, it may be the entrance)

(a massive mural on the ‘flight deck’ floor. still there, albeit defaced by spray paint)

(more of the flight deck floor. still mostly unchanged)

(a closed off floor, presumably still having work done on it- likely the carnival)

(…and back down into funland.)

Then, in 2011, the end came. In the final months, the rent and bills were no longer getting paid for the floors, despite them seemingly still making a profit off of tourist trade and the fledgling dance game communities. Internal rumblings over consistent money mismanagement and disagreements over the lease went on for some time.

After tensions came to a head with Criterion, the landlord cut off the electricity supply for the arcade, and locked the fire exits on the 3rd of July. Since the Trocadero was proposed to be a hotel in the coming years anyway, they weren’t too interested in getting it back up and running in any form, and it was soon clear Funland would never return.

An outpouring of support and sadness followed on social media and forums – by this point Funland had been a staple of Piccadilly Circus for over 20 years, and good or bad, lots of people had lots of memories. The official Facebook page tried to lift spirits with talk of moving to a different location, but it was not to be. Funland, possibly one of the greatest arcades of all time to the players, was gone.

The final years (2011-2014)

After the Funland’s closure, the Trocadero became virtually empty, both literally and figuratively. A small attempt was made to bring arcades and 3D experiences back to the centre in the basement, with the ‘5D World’ and ‘Star Attraction’ arcades, but it was nothing compared to what Funland and Sega World were. It was rumoured that the rent was free for these places, with them taking only 20% of the profits made and the rest going to Criterion.

(virtually all that was left in the Troc after Funland closed)

More games were dotted around the 1st floor, with the only open attractions on that floor now that Funland was gone being the rundown Cineworld Cinema, still raking in some money from tourists and film-goers in the area, and a makeshift laser tag game where the IMAX once was situated.

A substantial amount of the Trocadero was not open to the public now – in fact, less than back in 1984 when it had initially re-opened as a shopping centre. The old décor and signs of Funland were still up, as well as a gaping hole in the ceiling where the second escalator once was, giving lasting reminders of the former glory the place once had, now sadly long gone.

The community spirit of Funland still remained somewhat in the Trocadero’s underground access tunnel, which had now been transformed into a dancing area – thanks to the the dance games, whose step charts allowed for freestyle routines, there was crossover with London’s street dance and b-boy scene.

The last two big name tenants the Trocadero was hanging on to, HMV and Planet Hollywood, had now closed down and relocated to other premises in the capital, the former as a result of their unfortunate ongoing administration. The remaining shops left in the Trocadero hit a new low when a fake goods raid was carried out, with many extremely negative reviews now being posted on TripAdvisor.

But the final, final end for the Trocadero happened during February of 2014. Plans for the hotel and shops had been granted since 2012, and work needed to start soon. Because of this, the central atrium of the Trocadero, with the two arcades, laser tag, and tourist stalls, was completely bordered off on the 24th of that month.

Some dilapidated remains of the decor, unchanged since the 90s, could be seen in the corridor that had been made for the Cineworld Cinema to stay open for business during construction, and the very last remnants of Sega World and Funland could be seen here- a few old, broken arcade cabinets, still taking money. However this was the farthest cry from what it once was yet, and simply put, the Trocadero was now completely dead.

R.I.P. Trocadero, gone but not forgotten.

Loose ends, and the future of the Trocadero

The Cineworld Cinema (previously owned by MGM and Virgin), with the very last cabs scattered around it’s entrance, only lasted until later in 2014. It was replaced and refitted into a Picturehouse Central in 2015, which also occupied some of Funland’s former space. The last part of the Trocadero’s status as an urban complex, the entrance shopping arcade, was later taken out and replaced by just one large tourist shop.

The other Sega arcades around the UK, mentioned earlier in this article, suffered a similar fate to Sega World London. Needless to say, their owners never put much care into running them. By the 2010s all but two of the locations had long since closed down – Bournemouth, albeit made significantly smaller, was renamed to Fun Central under new ownership, and Southampton, the final holdout, closed down in February 2013 with the demise of the shopping centre it was located in. The Leisure Exchange, the final operators of many of the locations, are believed to have dissolved.

(around 1/4 of Sega World Bournemouth became an arcade called Fun Central)

In a way, Sega were in fact part of a vanguard that initiated a change in the UK’s amusement arcade sector through their venues – whether it was a positive or negative one is up for you to decide, but despite it playing a part in the eventual near total death of the arcades as gamers knew them, they did precipitate a shift towards a more family entertainment focused way of running things, on which – among other causes, good and bad – the amusement industry thrives on to this day.

All of the former Sega World features and trappings are believed to no longer exist – with some notable exceptions, including the Sonic reception statue, currently privately owned. Some of Funland’s games were sold to other arcades like The Heart Of Gaming in Croydon (VS City cabs, Naomi DX’s), and others went to JNC Sales, who then auctioned them off themselves, and were bought by arcade machine collectors and other venues.

Some of them were also relocated by Family Leisure to Las Vegas Arcade in Soho, where they still reside in its basement alongside new imported cabs like Taiko No Tatsujin and Sound Voltex. It effectively became the main arcade in London for the rhythm game scene in the 2010s, with other venues like Vega opening off of the back of its success. The spirit of Funland still somewhat remains in this inner city venue.

Despite the closures of several locations decimating the total number of them, Joypolis operations in Japan hung on with the consistently successful Tokyo site in Odaiba. Recent years have seen Sega face further financial difficulties, signing away the rights for the remaining parks to Chinese company China Animations – who rebranded their division, Sega Live Creation, to CA Sega Joypolis – hopes remain high internally that these remains of Sega’s dreams can continue on as long as they can.

And, around 4 years on from final closure, here is the Trocadero as of typing this:

As can be seen, the building has been stripped completely bare now. It could be said that this isn’t much work for 5 or so years of construction, but the Troc was of course occupying well over 8 floors, with a large gaping hole where some had been knocked through in its centre, making the construction of a hotel a challenge.

And if looking hard enough, you can convince yourself the yellow and black wall paint leftover on one of the floors is a very small trace of Sega World. When it’s come to that though, you know it’s all over.

Epilogue

There is a certain kind of hope for the Trocadero – despite the logistical problems in anything filling its space easily, some things have begun to. For one, The Crystal Maze Experience, a tourist attraction re-enacting the popular TV game show, has somewhat brought the centre back to its roots in providing tourist entertainment. Some of its tatty shops have also been cleared out in favour of restaurants, including a Forrest Gump themed one named Bubba Gump, and a Chinese hot pot chain, Haidilao. Green shoots of recovery are indeed appearing.

But all in all, the Trocadero remains a fascinating part of Central London’s recent history, especially if one is interested in gaming-related matters. When looking past the perceived wisdom made by some that it was all naff and deserved to fail, the vast history of failed tourist attractions and schemes is still impressive, yet also lamentable, considering the genuine brilliance of a lot of it, or at least the ambition.

Who knows what the future may bring for the building, but for some time to come, it will have still meant something for a certain amount of people, whether it be making their gaming dreams come true or changing the course of their social lives forever.

If little else, the ambition of Sega and the role Funland played in a fledgling social moment that has now diminished are things that should be remembered and acknowledged more in gaming circles – particularly the ones that have exhausted the ideas of ‘retro gaming’, and could do with a wider scope of interests.

It was a social thing, for a time. And for a lot of that it was futuractive.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

…and that’s it.

My first proper blog post, and it took an incredibly long time to make. 2 months were spent sourcing videos and pictures, and making sure everything was verified and true, not to mention losing and eventually regaining the work I’d done.

Huge thanks to everyone who uploaded the videos here and provided scans of gaming magazines which covered this, without them this probably wouldn’t have been possible. And as big as this article is, I have had to cut some content out that just didn’t fit well with the rest of it.