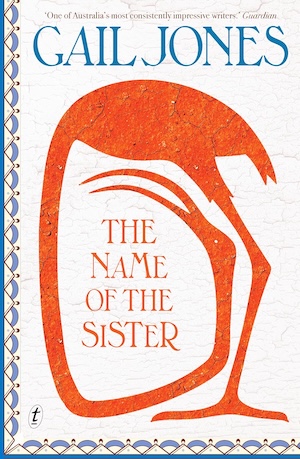

Fiction – paperback; Text Publishing; 202 pages; 2025. Review copy courtesy of the publisher.

Gail Jones is one of Australia’s most accomplished writers. Indeed, last year she was inducted into the Western Australian Writers Hall of Fame in recognition of her contribution to literature.

I think of her as a deeply thoughtful novelist (I’ve read five of her novels at last count) and feel that to appreciate her work best, you need to read it in a deeply thoughtful way. Her writing is not something to rush through.

Given this, I was mildly surprised to see her latest novel, The Name of the Sister, billed as a thriller and with elements of the crime and suspense genre thrown in. The story just so happens to have a mystery at its heart, which is perhaps why reviewers, blurb writers and publicists describe it as such, but I still think it’s best described as literary fiction.

Indeed, it’s a deeply contemplative look at how humans make sense of the incomprehensible through storytelling, and how we craft narratives from facts and half-truths to understand the often-fraught world around us.

The mystery of Jane Doe

In this story, we meet Angie, a freelance journalist, who is intrigued by a case in which a woman is found, disoriented and unable to speak, on an outback road “thirty or so kilometres north-east of Broken Hill” (page 3).

Who is this “Jane Doe”? Why is she mute? Where has she come from? Is she the victim of an unspeakable crime?

On the television her face was narrow, brown in unnatural light and unearthly in appearance. There was a dismal tone to the report, and a banner at the bottom of the screen said Unknown Woman: Information Wanted. She did not know who she was. No one knew who she was. No one knew where she had come from. She had simply arrived. Her life was a puzzle waiting to be solved, so she carried the enticing air of one considered mysterious (page 2).

The investigation is led by Detective Inspector Beverly Calder, who is known to Angie (the pair went to the same primary school and grew up in the same small town). Bev claims it won’t take long to work out Jane Doe’s identity.

“Just a matter of time. We sift all the stories and chuck out the nutters and eventually, with what’s left, there’ll be a few DNA checks to find the match. And we’ll follow up certain related or non-related men. Blokes who claim to be an ex or a boyfriend are always worth a second look.”

Bev turned around, checking, as if someone might be listening. “The bigger mystery is what happened. Why she was out there and the type of crime. If she’d been a runaway, a captive, victim of a psycho, whatever.” (page 11)

Having seen reports in the media, dozens of people from Australia and beyond step forward, claiming they know Jane.

Angie, intrigued by the appearance of a woman rather than the typical disappearance, meets these people to find out what claim they have on her, even though she’s…

uncomfortable entering the genre of ‘true crime’ … At some level she was appalled by the public appetite for stories of hurt, and by the addictive excellence of crime dramas on television (page 15).

She convinces herself that she’s not trying to solve the mystery. She’s merely researching a story and putting something together that is much broader, that examines the cultural and societal fallout of such “crimes”. Her purpose?

The honourable gathering of stray and neglected feelings: mocked convictions, theatrical needs, implacable desire, genuine grief (page 90).

But even when Jane’s identity is revealed on page 63 — “Not much of a mystery, huh?” as Bev puts it — it doesn’t discourage claimants from calling Angie and sending her messages.

Interrogating the genre

Although The Name of the Sister flirts with the language and structure of a crime novel, Jones interrogates them by turning the spotlight onto the aftermath and ambiguity of trauma.

The novel considers what it means to tell stories about violence, and what gets lost or twisted when pain becomes a form of public spectacle and entertainment.

Angie’s discomfort with the trappings of true crime — its moral murkiness, its voyeurism — runs throughout the book, making it less about solving a mystery and more about questioning why we’re so drawn to them in the first place.

Cracks beneath the surface

Running alongside the investigation is Angie’s marriage to Sam. On the surface, their relationship is affectionate, calm and supportive. But the novel hints at a drifting apart that neither of them seems to realise.

Jones threads in glimpses of comfortably middle-class life through scenes involving books, music and weekend rituals. At times, these feel slightly forced, almost as if she is trying to pad out the story. There are many references to John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, which made me wonder if she was using it as an allegory, although its purpose was lost on me!

A quietly rewarding read

What stays with me after finishing The Name of the Sister is not the resolution of the case but the mood of the novel. Jones hasn’t written a thriller in any traditional sense (mind you, the ending is a little incredulous). Instead, she’s written something more unsettling and thoughtful — a book about mystery, yes, but also about memory, grief and bearing witness.

It asks us not only to observe but to reflect, and perhaps to question the commodification of crime and trauma. And like much of her work, it rewards the kind of reading that takes its time.

Lisa at ANZLitLovers has also reviewed this.

If you liked this, you might also like:

‘Highway 13’ by Fiona McFarlane: A collection of twelve linked stories exploring how a serial killer’s crimes ripple through lives across time and place.

Gail Jones lives in Sydney, NSW, but was born and grew up in Western Australia. She studied at the University of Western Australia, where she later also worked as a lecturer in English, communication studies and cultural studies. This means this book qualifies for my #FocusOnWestAustralianWriters. You can find out more about this reading project, along with a list of West Australian books already reviewed on the site, here.

Discover more from Reading Matters

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.