At the time I originally purchased the subject of today’s blog post, way back in June, 1975, it had been over two years since I’d bought an issue of any of Warren Publishing’s black-and-white comics magazines (with one exception, which I’ll get to in a moment). Half a century later, I’m not entirely sure how or why I’d grown so cold so quickly to Warren’s fare, given that I had been reading both Vampirella and Eerie quasi-regularly for some time prior to that (for whatever reason, I never bought more than a single issue of Creepy, at least not in this particular era). I do recall that I’d lost interest in Vampirella after its ongoing Dracula plotline got spun off into its own series in Eerie, and that I was subsequently disappointed when that series petered out inconclusively after a mere three episodes. Perhaps that was all it took to turn me off, especially since by mid-1973, I had other options for reading “mature” comic-book stories about Dracula — as well as other horror-oriented subjects — thanks to Marvel Comics’ new black-and-white line. As for the fourth comics title that Warren would add to its line in early 1974 —The Spirit — my younger self wasn’t sure what to make of it at all (though I do remember flipping through an early issue or two and being bemused by the discovery that one of my favorite contemporary comics artists, Mike Ploog, seemed to have copped a good bit of his style from this Will Eisner fellow.)

The one exception to my moratorium on buying Warren that I’d made in those last two years had been in July, 1974, when I’d picked up Eerie #59 — an issue which was allegedly an all-reprint collection, and included several stories I already owned, sort of. I use the qualifying terms “allegedly” and “sort of” because, while the artwork for all ten “Dax the Damned” stories featured there had indeed appeared in Eerie previously, all ten had also received new scripts by Budd Lewis for this encore presentation — a move that turned the sword-and-sorcery adventure strips illustrated (and originally written) by Spanish artist Esteban Maroto into what amounted to completely different stories than they’d been in their initial English-language versions.

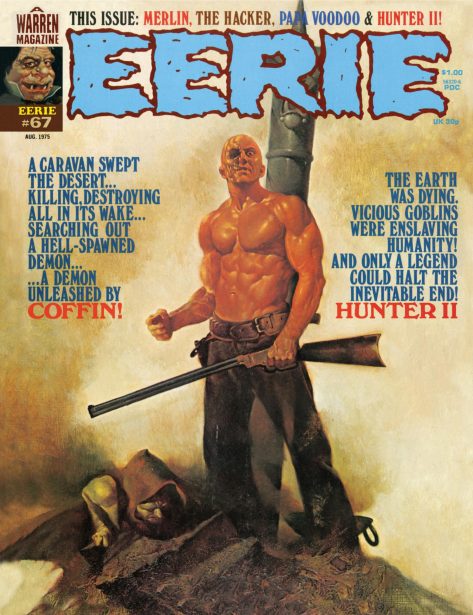

But, anyway, that purchase — which I figure was motivated as much by my general enthusiasm for the sword-and-sorcery genre as by my admiration for Maroto’s artwork — was the last Warren I’d buy for almost another year… until June, 1975, and Eerie #67. And what motivated me to pick up this particular issue? It pretty much came down to one word — one name, to be more specific — printed near the top of the magazine’s cover:

If you’re a longtime regular reader of Attack of the 50 Year Old Comic Books, you may already be aware of this blogger’s abiding interest in the legend of King Arthur in all its permutations. That interest, which first developed in my early teens, was definitely in full flower by 1975. Pretty much any book, movie, TV show, or comic book with an Arthurian theme was bound to get my attention; my grabbing up a Warren magazine featuring a 12-page story about the famed wizard of Camelot was thus a no-brainer. The fact that said story would turn out to have been drawn by one of my favorite fantasy artists — the aforementioned Esteban Maroto — was a welcome bonus, but I’d have dropped a dollar for this book no matter who the creative team had been.

Of course, the Merlin-starring “The Kingmaker” was but one of five stories to be found within Eerie #67’s pages; and, as it happened, it was the last story in the magazine. But while I can’t guarantee that my seventeen-year-old self didn’t flip to the back of the issue to read that one first fifty years ago, we’re going to follow this blog’s accustomed protocols in our discussion today, and take ’em in order of presentation, one by one.

Actually, however, we’re going to lead off not with Eerie #67’s first story (which also happens to be the subject of the book’s striking cover by the Spanish painter Sanjulián), but rather with its inside front cover — a dark, moody frontispiece by Bernie Wrightson:

Bernie Wrightson had been contributing work to Warren’s magazines for over a year at this point — basically, ever since he’d departed from DC Comics’ bi-monthly horror comic Swamp Thing. While he was still doing the odd cover or inking job for DC (and even on occasion for Marvel), Warren was the artist’s main comic-book home during this period. (Alas, my younger self missed out on all of Wrightson’s full stories for Warren when they were first published, so I won’t be be able to blog about any of them here.)

Along with the advent of Wrightson, there had been other notable changes in Warren Publishing’s three core black-and-white titles since the last time I’d been paying much attention. Most of these were attributable to editor Bill DuBay, who’d first come to Warren as a freelance artist and writer in 1970, then moved into a staff position soon after. Ascending to the top editorial spot in late 1972, DuBay had continued some existing trends, such as the line’s growing reliance on Spanish artists (most of whom, like Maroto and Sanjulián, came from the Barcelonan agency Selecciones Ilustradas [S.I.]). But he also nurtured a group of new young American writers, such as the aforementioned Budd Lewis, who worked almost exclusively for Warren. Eventually (and perhaps not entirely intentionally), DuBay managed to establish “a uniform approach to the style and mood of the horror in the magazines, an approach that was as strong as, but completely different from, the approach that [earlier editor Archie] Goodwin used.” (Richard Arndt, Horror Comics in Black and White: A History and Catalog, 1964-2004 [McFarland, 2013].)

Among the most significant developments that occurred during DuBay’s editorial tenure was the establishment of clearly separate identities for Warren’s two oldest comics titles, Creepy and Eerie. As the original Warren horror comic, Creepy stuck to its EC Comics-derived roots as an anthology title featuring one-off short stories; Eerie, on the other hand, moved in a different direction, becoming primarily a showcase for continuing series characters.

There had been occasional serials in Warren’s comics almost since the beginning, such as the “Adam Link” stories that had appeared in issues of Creepy from 1965 to 1967; and, of course, a character-centric approach had been embraced by Warren’s third title, Vampirella, years earlier. Continuing characters had been a part of Eerie itself at least since the first of writer Steve Skeates’ three stories of “Prince Targo” appeared in issue #36 (Nov., 1971). But it was only on Bill DuBay’s watch that continuing series would become the title’s focus, beginning with such traditionally-themed horror features as “The Mummy Walks”, “Curse of the Werewolf”, and, as mentioned earlier, “Dracula”. While standalone stories would continue to appear from time to time, the pages of Eerie were more and more given over to an ever more diverse, constantly changing assortment of ongoing features; the issue we’re looking at today is a particularly strong example of the “new” Eerie, as all five stories contained within are installments of series.

First up, we have “Coffin”, a horror-Western hybrid that had made its debut in Eerie #61 (Nov., 1974), and returns for its second episode here; like that premiere outing, as well as all subsequent Coffin adventures, “Death’s Dark Colors” was written by Budd Lewis and drawn by José Ortiz.

As we’ve already noted, Lewis was among the group of young writers recruited and/or nurtured by Bill DuBay. Selling his first story to Warren in late 1972, by mid-1974 he was one of the company’s most prolific writers; save for one, all of the stories in Eerie #67 were scripted by him. Lewis’ career in comics would last for only as long as Warren Publishing itself, however. After the company’s collapse in 1982, he left the industry to go work in film and television; sadly, he seems to have faced some serious economic challenges in his later life, as it was reported in 2011 that Lewis and his wife were at that time facing homelessness. Budd Lewis passed away in 2014, at the age of 65.

José Ortiz, like most of Warren’s Spanish artists, was associated with the S.I. agency; also like most of them, he was already an established illustrator with a long list of professional credits prior to coming to Warren in 1974. Writing in The Warren Companion (TwoMorrows, 2001), David A. Roach identifies Ortiz as part of what he calls the “second wave” of Warren’s Spanish illustrators, who to some extent displaced a number of the artists who’d preceded them at the publisher; Roach also notes that, with an eventual total of 219 stories drawn for Warren, Ortiz was “by far their most prolific artist.” Unlike Budd Lewis, Ortiz continued to work regularly in comics following Warren Publishing’s demise, returning his focus to the European market from which he’d come; he died in 2013, at the age of 81.

The very first time I saw Coffin, I immediately assumed that he was essentially a Warren knockoff of DC Comics’ Jonah Hex, a similarly disfigured character who’d first appeared in All-Star Western #10 (Feb.-Mar., 1972), and who in 1975 was holding down the lead feature in Weird Western Tales. Fifty years later, I see no reason to question my original supposition regarding Coffin’s initial inspiration; having said that, it must be acknowledged that the similarity between the two heroes is primarily visual. At least in his original conception, there was nothing supernatural about Hex, who’d come by his horrific facial scarring by entirely mundane (albeit violent) means; Coffin, on the other hand, had been cursed by a Native American sorcerer to endure eternal life… though only after he’d already been staked out in the desert sun to die and had had half his face eaten away by ants. Ouch.

Regular readers of this blog may recall our Detective Comics #450 post of about a month back, in which we quoted artist Walt Simonson regarding the influence of José Ortiz’s work on his “Batman” story published in that issue. Simonson described the Spanish artist as “a master of chiaroscuro, master of black and white”; and while that mastery is on display throughout the present story, I think it’s especially evident on the page shown directly above.

When dawn comes, Coffin takes refuge from the merciless sun in the meager shade of a rocky outcropping. He sleeps until nightfall, then slakes his thirst by catching and sucking the blood out of a lizard before once more resuming his journey…

Coffin cautiously proceeds through the town of Cemetery Creek, but finds no sign of any human inhabitants, living or dead, other than another discarded handbill from the “Caravan of Death”. He helps himself to some abandoned food and drink in the empty saloon, then acquires some clothing and other supplies from the town’s store (for which he leaves an I.O.U.), as well as a horse he finds in a stable. Thus equipped, he continues on his way, now in conscious pursuit of “that camel wagon-train“. But, before long, he stumbles upon a horrific sight…

Coffin continues his relentless pursuit, picking up one more of the Caravan’s calling cards along the way. Then, at last…

Lewis and Ortiz would produce one additional adventure for Coffin — it appeared in the following issue, #68 — before wrapping up the series for good in issue #70 with “The Final Sunrise”. That last episode allowed Coffin to end his curse and finally achieve the peace of true death — although to get there, he had to lie back down on the same anthill he’d been staked out on in the first place and allow the little buggers to finish the job. Ouch, redux.

This was illustrative of Bill DuBay’s approach to the series he ran in Eerie, which were regularly touted in the letters columns and elsewhere as always intended to have a beginning, middle, and end, rather than run on indefinitely in the way of most continuing features in comics. Of course, the endings were rarely (if ever) fully happy ones — the conclusion of Coffin’s saga was pretty representative of the Eerie norm — but given the title’s horror-comic foundation, that was reasonable enough.

And even if an individual series did culminate in a firm, definite ending, that didn’t necessarily take a sequel off the table — case in point being the very next story in Eerie #67, which serves as the debut episode of a not-quite-brand-new feature, “Hunter II”.

Cover to Eerie #69 (Oct., 1975), which reprinted all six chapters of the original “Hunter” serial. Art by Ken Kelly.

The original “Hunter” had debuted in Eerie #52, and subsequently ran through six consecutive issues, reaching its conclusion in issue #57. The story of a hunter of “demons” (actually mutants) bearing the very on-the-nose name of Demian Hunter, it chronicled the hero’s journey through a post-apocalyptic America in search of the mutant who’d raped his mother and thereby fathered him. In his helmet and skintight suit, Hunter could be said to follow in the footsteps of such heroic science-fiction forebears as Buck Rogers and Adam Strange; it could also be said that he came about as close to looking like a conventional DC or Marvel superhero as any Warren series character ever would.

“Hunter” was somewhat unusual among Warren series in that it had not one, or even two, but three writers. The first two installments were written by Rich Margopoulos (like Budd Lewis, a Warren mainstay during the Bill DuBay era), while the two middle episodes were by Lewis; DuBay himself stepped in to script both concluding chapters. The art in all six strips was by Paul Neary — something of an outlier among Warren’s creative roster in this era, as he was neither Spanish nor American, but British.

In 1969, Neary was a student at the University of Leeds when, having traveled to New York on holiday, he managed to work in a visit to the offices of Warren Publishing… and to leave with a script in hand. Per his own account in a 2008 interview, he spent months working on that first 7-page story, which eventually saw print in Eerie #41 (Aug., 1972). The young Englishman quickly became a regular contributor to Warren’s line under the tutelage of Bill DuBay, whom he referred to in the same interview as “a sort of mentor to me. Big brother, probably.”

The original “Hunter” serial had ended in a typically downbeat fashion, with the titular hero ultimately succeeding in his quest, but losing his life in the process. As we readers of Eerie #67 were about to discover, however, though Demian Hunter was no more, his heroic legacy lived on…

While the pages shown here demonstrate Paul Neary’s facility as both a draftsman and a storyteller, what really makes his work of this period stand out among his peers is his inking — within which category of artistic activity I include his liberal and deft use of screentone in a variety of patterns. The richness and elegance of these finishes is so integral to the ultimate effect of the work that in later years, when I came across stories that Neary had pencilled but not inked — his 1984-87 run on Marvel’s Captain America, for example — I wasn’t immediately certain it was even by the same artist. Perhaps that had something to do with Neary adapting his personal style to better accommodate Marvel’s expectations in regards to the company’s “house look”, but I’m inclined to believe that it was at least as much about the differences in the inks and tones.

As we readers watch the battered traveler first stagger, then crawl away from his brutish attackers, the as-yet-unseen speaker tells his listener, the equally unseen Karas, how the legendary phoenix, feeling the weight of years upon him, built his own funeral pyre, “setting it afire with a single spark from the sun. He died among the flames of his own existence.”

Karas rides out as Mandragora has bid him; but, seeing no sign from atop the ridge of any travelers coming, he’s about to turn around and go home, when something catches his eye…

Karas is skeptical, saying that there’s been no sightings of any demons in the last twenty years. But Mandragora takes Browne Loe’s tale seriously, as he first heard rumors of “monstrous beings, living in dark places” several months ago, and has been investigating ever since…

“With the new time-shell the Earth will live, because the fated second of extinction will never come,” explains Mandragora. “It doesn’t exist in the new shell… In the new time there is no moment to die.”

Karas admits that he finds all this a little confusing (and hey, he’s not the only one), but he’s nevertheless willing to accept what Mandragora is telling him. However, he does wonder about how the demons fit into it all. After correcting his young companion’s nomenclature — these creatures are properly referred to as goblins, not demons — Mandragora opines that to learn much more than they already know, they’d have to question a goblin in person. Fine, says Karas, I’ll go fetch one. “No!” cries an alarmed Browne Joe. “Don’t go near them, boy… they are like mad dogs on fire with blood taste!”

Budd Lewis and Paul Neary continued to chronicle the adventures of Karas Hunter for another five episodes; in the last, which ran in Eerie #73 (Mar., 1976), the young hero discovered that most of what Mandragora had told him was bullshit; the White Council not only lacked the capability to save the whole Earth, they didn’t even intend to try. On the other hand, the serial concluded with the Earth in fact spared, and Hunter himself still among the living — which is about as happy an ending as any Eerie series protagonist ever got.

“Hunter II” received a coda of sorts several years later, in Eerie #101 (Jun., 1979) — the character got through that one alive, too, if you’re wondering — but though Budd Lewis provided the script for that story, Paul Neary had since moved on from Warren, his last job for the company having appeared in 1977. After departing from Warren, Neary worked for British publishers for a few years before returning to American comics both as a penciller (in addition to the Captain America stint mentioned earlier, he also drew the Nick Fury Vs. S.H.I.E.L.D. miniseries, as well as issues of Ka-Zar the Savage) and as an inker — the latter mostly over the pencils of his fellow Brit, Alan Davis, with whom Neary memorably collaborated on “Batman” in DC’s Detective Comics and on Excalibur for Marvel. Neary soon transitioned to working almost exclusively as an inker, eventually teaming with yet another British artist, Bryan Hitch, on such high-profile projects as DC/Wildstorm’s The Authority and Marvel’s Ultimates. He passed away not much more than a year ago, on February 19, 2024, at the age of 74.

We come now to our third story of this issue of Eerie — which also happens to be the third and final entry in the “Hacker” series. Its creators have both been previously featured on this blog multiple times, so we’ll forego most of the general biographical details to focus on their history with Warren.

Writer Steve Skeates (here providing this issue’s only script not by Budd Lewis) had begun working for Warren in 1970, after already establishing himself with work at Tower, Charlton, and DC; earlier in this post we mentioned his three “Prince Targo” stories for Eerie, all of which started out as plots for Aquaman yarns Skeates reworked after DC cancelled the Sea King’s title. He’d continued to keep his hand in at Warren the last few years while also contributing stories to other publishers, primarily DC. As for artist Alex Toth, he’d already been in the business a couple of decades prior to becoming a vital part of Warren’s “glory days” of 1965-1967, at which time he’d collaborated with writer-editor Archie Goodwin to produce such classics as “The Monument”. Most of Toth’s recent comics work had been for DC, with his return to Warren having come just a few months prior to this, in Eerie #64.

The “Hacker” series, whose debt of inspiration to the “Jack the Ripper” murders of the late 19th century is obvious from the current story’s first page, had been launched by Skeates in Eerie #57 in collaboration with a different artist, Tom Sutton. Toth had come aboard with the second installment, which appeared in issue #65. Those two previous chapters are efficiently summarized over the next two pages…

Toth’s use of solid black panel borders throughout the story adds significantly to the story’s overall sense of darkness — a darkness that threatens to engulf Smythe and the other characters as it inexorably spreads out from the gutters (pun intended).

Arriving at the Black Swan, Inspector Smythe has no difficulty locating Panama Red. But when he begins to ask the initially brash and self-assured woman his questions about “the man in the black hat and coat”, she becomes frightened…

As the head count rises (sorry), Smythe continues to comb the Soho “red light” district for clues. But his investigations bear no fruit, until, one night…

The twist ending of “The Hacker’s Last Stand!” falls a little flat — the revelation that Smythe and his Scotland Yard colleagues should have been looking for a butcher all this time, rather than a simple chef or garden-variety cannibal — isn’t really much of a payoff, given that it resolves virtually none of the narrative tension Skeates has established over three installments — and it’s also bleak to the point of nihilism, at least for those who prefer their Gothic horror serials to take place in something akin to a moral universe. But there’s no complaints to be had with the virtuoso performance of Alex Toth, whose graphic mastery makes this one a keeper, regardless of the script’s flaws.

Our fourth story of the issue introduces a new series, “Papa Voodoo” — though, as the first page’s introductory captions make clear (at least for those readers who’ve been following Eerie for a while), it also parallels the issue’s earlier debut of “Hunter II” in that it, too, is the first chapter of a sequel to a prior series — in this case, “Spook”:

Cover to Eerie #65 (Apr., 1975), which featured the final “regular” adventure of the Spook and Crackermeyer. Art by Ken Kelly.

“The Man Named Gold!” is the work of Budd Lewis and Leopold Sánchez, about whom we’ll have more to say in a moment. But “Spook”, which had debuted in Eerie #57 (Jun., 1974), had originally been written by Doug Moench. Clearly inspired by the same contemporary mini-vogue for voodoo that had already inspired the creation of two Marvel Comics series protagonists, Brother Voodoo and the Zombie, the initial episode introduced the Spook, a powerful, and fully sentient, Black zombie who operated in the pre-Civil War American South, defending and/or avenging other Black people — usually against white enslavers (though not exclusively so). Moench scripted the first three installments, the second two of which both ran in Eerie #58; Budd Lewis would take over with the fourth episode, published in issue #62, and continue on through the seventh and last installment in #65.

While the very first “Spook” story was drawn by Esteban Maroto, the series passed thereafter into the hands of Leopold Sánchez. Like José Ortiz, Sánchez belonged to the “Valencia group” of illustrators who arrived at Warren several years after the advent of the first wave of Spanish artists that had included Maroto. Sánchez’s first “Spook” yarn, Eerie #58’s “Webtread’s Powercut”, was also his first published job for Warren; his work would continue to appear in the company’s publications through 1982. Following the demise of Warren, Sánchez’s most visible project appears to have been “Bogey”, a science-fiction/crime series produced in collaboration with writer Antonio Segura that had both Spanish and British printings; the artist passed away in 2021, at age 73.

Half a century on, “Spook” remains a somewhat problematic series. On the one hand, it commendably featured Black protagonists in an era when they were still relatively rare in American comics; on the other, it occasionally evinced a troubling racial insensitivity on the part of more than one of the creative personnel behind it. We might start with the name of the series (and of its main character) — a word sometimes used as a derogatory term for a Black person. In an interview conducted decades later for 2001’s Warren Companion, Doug Moench was at some pains to stipulate that he was given the name “Spook” by his editor, Bill DuBay, and had himself had no idea that it could be taken for a racial slur. Assuming that’s true, then we might still suppose that DuBay meant for the use of the term to be ironic, if ill-advisedly so. (If anyone ever asked the late editor [who died in 2010] about this matter directly, your humble blogger is unaware of it.) But it’s harder to wave away the rather odd sensibility in regards to race that enters into the series once Budd Lewis comes on board as a writer.

Panel from “Coming Storm… A Killing Rain!” in Eerie #65 (Apr., 1975). Text by Budd Lewis, art by Leopold Sánchez.

With his first “Spook” script, Lewis introduces a new, second protagonist for the series — Crackermeyer, a free Black man and powerful practitioner of voodoo. While opposed to evil and cruelty in all its forms, including slavery, Crackermeyer (who officially becomes the series co-headliner with its final installment in Eerie #65) doesn’t seem to be in any particular hurry to change the South’s status quo, going so far as to tell Union soldiers in that last story (set in 1862) that they should turn around and go home: “Our enlightenment will will free us when we’re ready!” Not to say that there couldn’t have been at least one Southern Black man in 1862 who felt that way, or that Crackermeyer’s ideas about freedom in general (see panel at right) are completely without merit — but at the very least, this seems to me to be a very presumptuous sentiment for a white author writing in the 20th century to put in the mouth of a Black man of the 19th century — especially one who, on some level, is supposed to represent Black heroism.

Issue #65’s “Coming Storm… A Killing Rain!” climaxes with a battle scene that has Crackermeyer and the Spook fighting both Union and Confederate troops in a vain attempt to halt the Civil War. It ends with the Spook’s being destroyed in an explosion, leaving Crackermeyer — a man already past middle age, or so it appears — to carry on alone into the sequel series, “Papa Voodoo”. Evidently, the practice of voodoo magic has a salutary effect on longevity — since, when we catch up with Crackermeyer in 1910, he seems awfully well-preserved for a man who must be over one hundred years old by this time…

Rufe Gold’s early morning duty involves “riding fence” — checking the miles of barbed wire fence on the Double Rocking R Ranch, and making repairs when needed…

After tending to Willard’s most serious wound — a slashed throat — a fearful Gold hastens on to his family’s home, which he finds engulfed in flames…

Gold’s relentless hunt continues for the next couple of years, as we watch him use clever tactics — such as setting up a circle of guns around an Apache camp, then firing them in succession to mislead the warriors into believing they’re under attack by a troop of soldiers — to overcome the odds against him…

As the first installment of what purports to be a sequel series to the adventures of the Spook and Cracklemeyer, “The Man Named Gold!” is something of a head-scratcher; other than having a historical setting and a Black protagonist, it has little in common with those earlier stories. Beyond the fact that Papa Voodoo himself doesn’t even directly participate in the story’s events, this a straight-up Western — even more so than this issue’s “Coffin” story, which at least included elements of supernatural horror. And while it’s not at all a bad story, it’s one that’s likely to feel somewhat familiar to anyone who’s seen the classic 1956 Western film The Searchers, or is knowledgeable about such relevant historical episodes as the 1836 abduction of Cynthia Ann Parker. In the end, the assured, evocative artwork of Leopold Sánchez is probably the most memorable thing about this piece.

Of course, it’s difficult to know where Lewis and Sánchez might have intended to take “Papa Voodoo” next, since they never produced a follow-up. But, that was the way it went with series in Eerie; for every one that racked up a reasonable number of chapters before bringing the main character’s narrative arc to a satisfying end, there was another one that never quite got off the ground (like “Papa Voodoo”), or just stopped dead in the middle of a storyline (like “Dracula” did in Eerie #48), its writer evidently having lost interest in the tale he was telling.

And then there were those series that seemed to my younger self to end much too quickly when I first read them five decades ago, but, on revisiting them now, strike me as having maybe concluded exactly when and how they should. Which brings us to the fifth and final story of Eerie #69 — the premiere, as well as the penultimate, episode of Budd Lewis and Esteban Maroto’s “Merlin”:

I can still remember how completely knocked out I was by this opening full-page splash the first time I saw it; beyond its simple gorgeousness, it seemed to hold out the promise of a full-fledged graphic retelling of the Arthurian legends that might go on for years and years. At the same time, my Arthuriana-stuffed young mind was both intrigued and puzzled (and perhaps even slightly annoyed) by some of the references in Lewis’ introductory text. Clearly, the comic-book scribe had done at least some modest amount of research, as there were bits related to the so-called “historical Arthur” of the late 5th and early 6th centuries that he wouldn’t have picked up from the standard English-language rendition of the legends, Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur (1485), or from its many derivations and adaptations. But what was this “Englonde” business? Surely Lewis knew that that name was derived from that of the Angles, who were part of the same broad wave of Germanic invaders that included those he here has Merlin call “the howling Saxons“. And why was he depicting Britain as being still under the imperial rule of “the Roman scum”? Again, surely he knew that the Roman legions abandoned the Empire’s northernmost province decades before King Arthur was supposed to have been born. Grumble, grumble… if only Warren had had the foresight to hire seventeen-year-old Alan Stewart as a consultant…

Eventually, of course, I set aside my grumbling and turned to the next page:

Naturally, Lewis and Maroto don’t allow you to get very far into this tale before reminding you that you’re reading it within an issue of Eerie — and, in its dark little heart of hearts, Eerie remains a horror comic.

As Merlin and his lovely “ward”, Snivel (not a character to be found in traditional Arthurian texts, just in case you’re wondering), ride away from the town and into the countryside, Snivel asks her master if it’s wise for him to be so bold as to leave his name behind with the slain Roman soldier. His reply itself comes in the form of a series of questions:

Unlike Snivel, Merlin’s old teacher, Belasius, is a traditional legendary figure, having first been mentioned (albeit under the name “Blaise”) in Robert de Boron’s poem Merlin, composed in the late 12th or early 13th century. So, too, the Well of Galapas, or Fontes Galabes, can be traced back even further, to Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae, composed around 1136… though, having said that, it’s entirely possible that Budd Lewis picked up both of these elements from Mary Stewart’s bestselling novel of Merlin’s early life, The Crystal Cave, which had come out in 1970 and had already been followed by a sequel, The Hollow Hills, in 1973 (The specific use of the phrase “the crystal cave” in the last panel above rather inclines your humble blogger to believe that’s precisely what happened.)

The notion of the sword Excalibur having been forged from meteoritic metal can be found in other modern works based on the Arthurian legend — but if there’s an example of such that predates Lewis’ employment of the idea, I can’t think of it at the moment.

Speaking as someone who has consumed more Arthurian media than may be good for him, I have to acknowledge that this is about as awe-inspiring an “origin story” for the Sword in the Stone as any I’ve ever seen or read. On both the textual and visual levels, it’s simply great stuff.

This brief shining moment is quickly interrupted, however, by a knock on the door. Merlin and Snivel assume at first that Roman soldiers have followed them, and so conceal themselves; but once Merlin sees that the man at the door is no Roman, he steps forward to address him:

“Fresh Roman ears“, yum! Yet another reminder that we’re reading this story in a horror comic.

In its original form (which is found in the aforementioned Historia Regum Britanniae), as well as most subsequent versions, the story of King Uther’s war against Duke Gorlois usually involves the latter attempting to hide his wife Ygraine away from the former in one of his own two castles. Why Lewis felt compelled to complicate matters by having Gorlois take the ill-advised (and improbable) step of stashing her in Uther’s castle, I have no idea. But that’s the thing with retelling legends… a writer can change the details up as they like, for better or for worse.

Will anyone out there reading this be surprised to learn that the interpolation of a demon named Cormaran into the traditional narrative of Arthur’s conception is an innovation of Budd Lewis? No, I didn’t think so.

“By Jove! Smashing!” Huh. I guess this Merlin is English (as distinct from simply “British”) after all.

In the original medieval chronicles and romances, the account of Arthur’s conception is pretty straightforward: Uther lusts for Ygraine, enlists Merlin’s help with creating a magical disguise, and then sleeps with her while pretending to be her husband. That may have been acceptable to a medieval audience (or at least to those members of it whose opinions have come down to us), but for modern media consumers, that synopsis more or less boils down to: Uther is a rapist, and Merlin is his accomplice. Modern Arthurian retellers thus face a choice between making Uther and Merlin sinister figures, or inventing some behind-the-scenes material undreamt of by Geoffrey or Malory that allows for Uther and Ygraine to be a credible romantic couple.

The latter direction has been the one more followed in recent decades, and Lewis at least leans in that direction, as he make it clear that 1) Uther really loves Ygraine, or at least thinks he does; 2) Gorlois is an unsatisfactory husband in Ygraine’s eyes, if not an outright brute; and 3) Ygraine is perceptive enough to see through Uther’s disguise during their night together (though she’s not given any choice beforehand in what happens, obviously), and subsequently chooses to accept him as her lover and (new) husband. Not to say that Lewis’ script would win any awards for feminism, then or now, but perhaps one can at least read the story without feeling one needs to take a shower afterwards.

In any event, that brings us to the end of Eerie #67 — which, from the perspective of half a century later, holds up pretty well as comic-book entertainment, at least to this reader. Though the contents never stray too far from Eerie‘s horror roots, there’s nevertheless an admirable diversity to its content — a diversity which extends to the range of artistic styles on display. Along with that diversity, the artwork is consistently of a very high quality — something which may be a little harder to claim for the writing, I’m afraid. Even so, despite the occasional flaws of Lewis’ and Skeates’ scripts, their work is never less than professional.

My younger self in the summer of ’75 was evidently less convinced by the overall worth of Eerie #67, however. I’m sure that I kept an eye out for #68 on the stands; but, when it arrived that July, and didn’t include a new chapter of “Merlin”, I passed on it. And, in fact, I didn’t buy another issue of Eerie until #74, by which time both the “Coffin” and “Hunter II” serials had already reached their ends (as things ultimately worked out, I wouldn’t find out how either of those story arcs were resolved until decades later, when I finally got caught up with both of them via Dark Horse Comics’ much-appreciated Eerie Archives reprint series). As you can probably already guess, I bought this issue for one reason and one reason only; it did, in fact, contain the eagerly-awaited (by me, if no one else) continuation (also the conclusion*) of “Merlin”:

While Budd Lewis returned as writer for this second and final episode, the artwork was by Gonzalo Mayo — a Peruvian artist with a style similar to that of Esteban Maroto, albeit a bit more cluttered-looking (at least to this reader’s eyes).

“A Secret King” comes in at the very generous (for Warren) length of 20 pages; given that this has already been a long post, and that I’m wary of taxing your patience, we’re not going to go through the whole thing in depth here. Suffice it to say that the bulk of the story is set some years later, when Arthur has grown to be around twelve years of age under the guardianship of Merlin and Snivel. Along with episodes drawn directly from the medieval tradition (e.g., the death of King Uther) and others nicked from T.H. White (e.g., Merlin teaching Arthur by turning him into birds and other animals), most of the narrative is devoted to an original plotline by Lewis that involves a scheme by the wicked Magicians’ Council to steal the Sword in the Stone. There’s plenty of rousing action involving Roman soldiers, inhuman Black Riders, and a water-dwelling, man-eating giant, and along the way, Arthur comes to live with Sir Ector and the latter’s son, Kay… just in time for the whole adventure to end exactly how you know it should:

Forty-nine years ago, my younger self hoped for further installments of “Merlin”, and was disappointed when none were forthcoming. But, as I suggested a little earlier in the post, I’m inclined today to think that it might be just as well that it ended when and where it did; after all, in tradition Merlin’s raising Arthur to the throne of Britain is the high point of his career. So why not quit while the protagonist is still ahead, rather than trudge along to what might have been a typically downbeat Warren series finale? At least we have these two “generally entertaining, somewhat irreverent, occasionally gruesome” episodes (to quote from my own Arthurian comics web site, itself now twenty-five years old [and looking every bit of its age]). Half a century later, that ought to be enough, methinks.

*For the record, several years later Budd Lewis authored another series for Eerie that might be considered a sequel to “Merlin”; entitled “Cagim”, it ran in issues #116, #117, #124, and #127, and concerned a young stage magician named Ambrose who discovers he’s actually the wizard Merlin. Based largely on the notion that Merlin lives backwards in time — a conceit broadly familiar to modern audiences, but one whose provenance actually goes back no further in Arthurian tradition than T.H. White’s 1938 novel The Sword in the Stone — there are no direct callbacks to anything in Eerie #67 or #74. So, your humble blogger feels comfortable in calling this sequence of stories another, separate take by Lewis on the same legendary source material, rather than a continuation of or sequel to his earlier project; others’ mileage might vary.