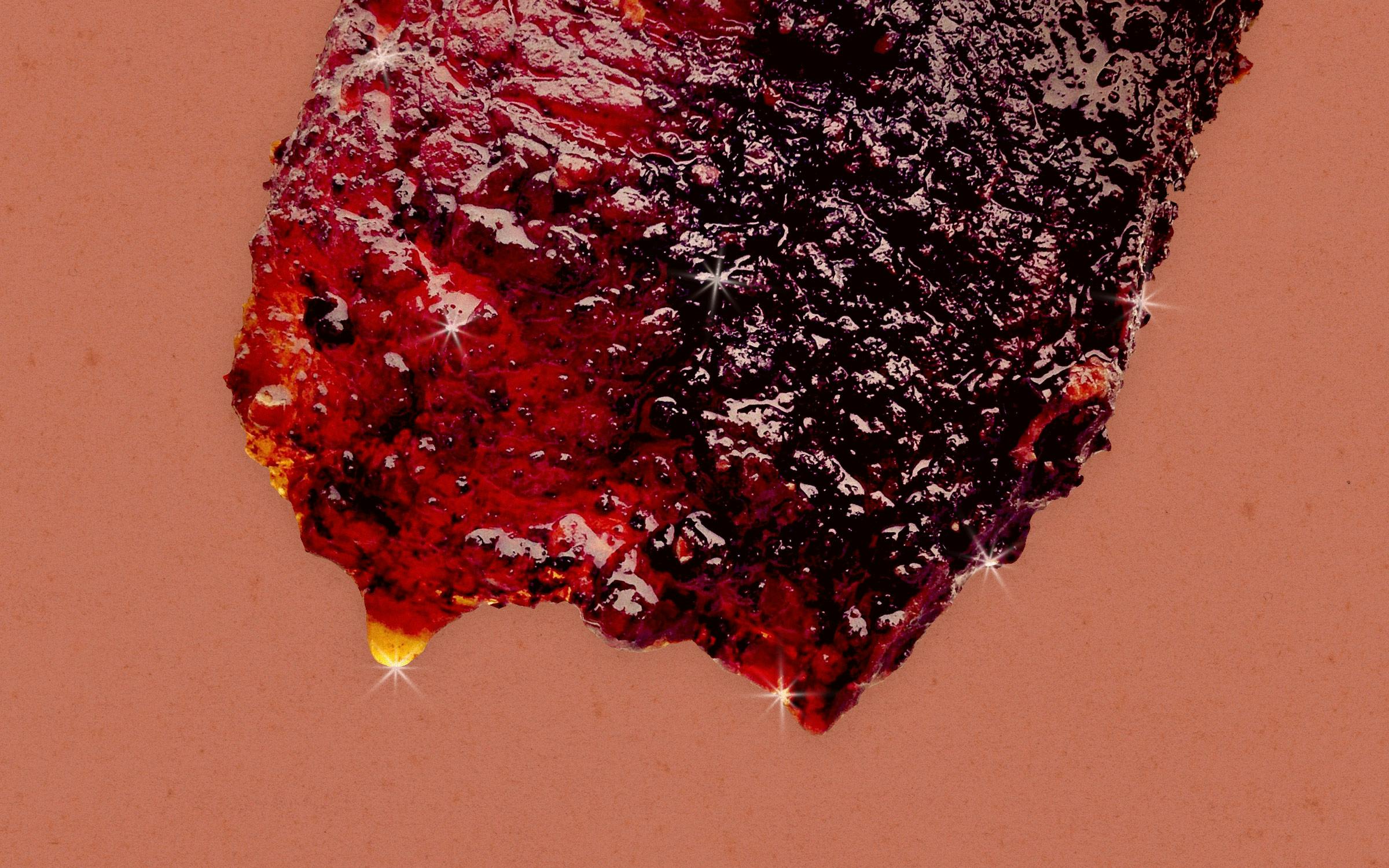

What makes brisket bark shimmer in the sun? Beef tallow. What drips from a freshly sliced beef rib held up for the camera? Beef tallow. What gushes forth from the cross section of a brisket being squeezed? Right again—beef tallow. (Actually, please don’t squeeze your brisket.) Some pitmasters pour beef tallow, or rendered beef fat, on their briskets to keep them juicy before wrapping them—that’s what you’re seeing on that soaked butcher paper blanket. It’s the byproduct most of us want with our smoked beef, but these days, it’s become a valuable commodity all its own. Beef tallow is hot now—especially when it’s chilled.

Miller’s Smokehouse, in Belton, has been selling beef tallow to customers for about five years. Until recently, it charged $10 for a quart of refrigerated tallow in a plastic container. The cooks had been using the fat in the restaurant’s kitchen for years as a substitute for butter, so it was similarly priced. “Now the perceived value has definitely gone up,” said co-owner Dusty Miller. The new packaging for the tallow includes a charming label on a glass jar, and the price is now $14 for a pint.

Blame the fat-flation on health trends that champion animal fats and a meat-heavy diet. If you’ve spent more than five minutes on social media in the last year, you’ve probably noticed that seed oils are the new villain. Influencers claim that frying foods in beef tallow is healthier than using sunflower, safflower, or the more common canola oil. Last October, Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy Jr. claimed that “seed oils are one of the driving causes of the obesity epidemic” in a post on social media that ended with, “It’s time to Make Frying Oil Tallow Again.” Nutrition scientists argue that consuming deep-fried foods regularly is detrimental to your health, no matter which oil you choose. They also warn that adding saturated fats like beef tallow to your diet doesn’t improve health. Despite that, melted fat from cows is enjoying a new level of popularity with the general public.

“It’s way different this year,” Miller said of the market for his restaurant’s beef tallow. He also gets more questions from customers about the joint’s use of seed oils. Lance Eaker has experienced similar queries at Eaker Barbecue, in Fredericksburg, which he owns with his wife, Boo. Their joint gets four out of five stars on the Seed Oil Scout app, which rates restaurants and products based on their use of seed oils. (I’ll have to take Eaker’s word for it, because the app requires payment to use.) Eaker would like to get that fifth star, but many of the couple’s Korean-influenced recipes require toasted sesame oil, whose flavor can’t be replicated with tallow.

Eaker said the popularity of tallow has given the joint a new revenue source. “It’s a bonus product,” he said, meaning that customers already pay for the fat that comes with every brisket. “We have an abundance of it, and my beef is really expensive.” The Eakers have always rendered the excess fat for use in the restaurant, but they couldn’t always find a place for the nearly three gallons collected from forty briskets every week. Now they can sell straight tallow directly to customers for $16 per quart—and fetch $2 more for the smoked version, which adds a touch of gold to the color. (If you’ve never seen well-filtered tallow for sale, it’s bright white and quite solid coming out of the fridge.)

Pitmasters divide the trim they remove from briskets into two piles—one for fatty meat and the other for just fat. The former is ground and used for sausages, burgers, or chili, while the latter is melted down in the oven or smoker. Grinding the fat makes the melting process more efficient, but cutting it into chunks also works.

Whether to melt the fat in the oven or the smoker usually comes down to whichever device has extra room. Keeping the pan uncovered in the smoker will provide some smoky flavor and coloration. Once the fat is melted, any small chunks of lean meat are filtered out through a sieve, and further filtration with a cheesecloth or a paper filter is common to remove impurities.

Bo Moreno, who owns Moreno Barbecue, in Austin, has to warn some of his customers that the tallow he sells is meant for cooking. He uses it to cook burgers and fries and adds it to house-made flour and corn tortillas. “There’s some kind of health craze where they’re putting tallow all over their face,” Moreno said, citing a few customers’ requests. He warns that his tallow hasn’t been deodorized, so those folks run the risk of walking around with a beefy aroma.

The added revenue couldn’t be coming at a better time for barbecue joints that have taken advantage of tallow’s reputation. The average wholesale cost for Choice-grade briskets last year at this time was $3.98 per pound. Last week it was $4.95. Back in March, Miller’s Smokehouse was paying $4.17 per pound. That jumped to $5.57 in its latest delivery. Given the volume of brisket he goes through, Miller equated that difference to “a small house a year.” If the restaurant doesn’t raise its menu prices, the only other thing he can do in response is be as efficient as possible. “We process every bit of the brisket, and it gets used in something,” he said.

Not everyone benefits from a higher demand for tallow. When Michael Wyont ran Flores Barbecue, in Whitney, he rendered his excess brisket fat to make smoked-tallow flour tortillas. After the restaurant closed, he formed Flores Tortillas and sold tallow tortillas to other restaurants. He took a hiatus from the business in 2022. When he fired up the operation again earlier this year, Wyont was in for a surprise. “We’re buying straight brisket fat,” he said, and the price had gone from 48 cents per pound to $1.25 in three years. That’s a meaningful difference when tortillas have so few ingredients.

Wyont said he doesn’t quite understand this latest consumer trend. “A lot of the customers that are concerned about seed oils still don’t buy [our tortillas] because our product isn’t gluten-free or organic,” he said. He believes he may turn a few more heads at the farmers market by using the word “tallow” as a marketing tool, but, he contends, “A majority of our business comes from the fact that it’s a good tortilla.”

Some restaurants are eager to tout their claims that brisket tallow is healthy. A sign inside Outpost 36 Texas Barbeque, in Keller, reads, “We use natural beef tallow for all of our frying needs. Using beef tallow is a more natural way to cook & is a healthier alternative to seed oils.” LocalCraft BBQ, in Newark, and 407 BBQ, in Argyle, have advertised their switches from seed oils to beef tallow for all of their frying. Helberg Barbecue, outside Waco, serves beef-tallow fries and crisps its smoked half chickens in a hot tallow bath just before serving. There’s even a new joint called Tallow Barbecue, which announced last month it’ll be opening in Tool later this year.

Some of these pitmasters aren’t just embracing tallow for the profitability or the marketing hype. Eaker said he has replaced the seed oils his family used at home with beef tallow from the restaurant. “This is what God created, not us. It’s natural, and we’ve been using it for thousands of years,” he said. Miller said using tallow has helped him and his dad stick to a carnivorous diet. “There’s a world in which barbecue is very healthy, especially brisket,” said Miller. And to the carnivore crowd, he said, “tallow is a health food now.”