Multiple attempts have failed for decades, but the dream remains alive.

One Canadian company has a head start on Chinese ambitions, and the combination of Trump and Musk may soon revive its bombed-out share.

Is The Metals Company the ultimate upcoming MAGA play?

The history of deep-sea mining

The deep sea doesn’t just contain treasures in the form of sunken pirate ships, but also vast amounts of useful metallic resources.

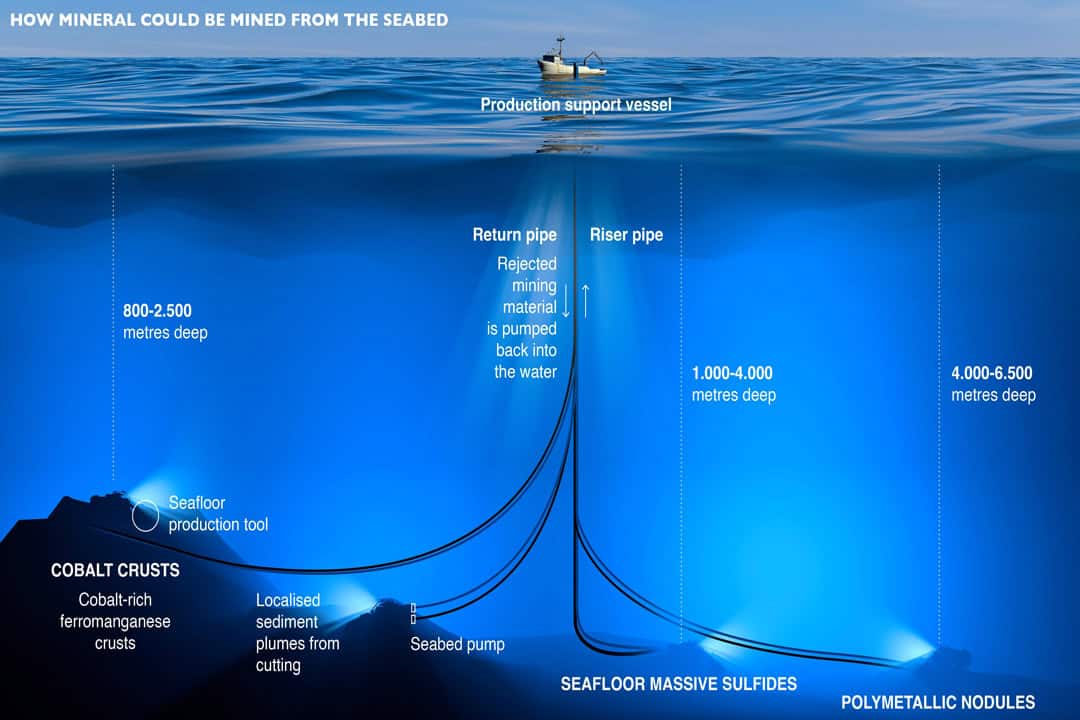

So vast, in fact, that all of humanity’s future metals needs could be satisfied by mining the ocean floor, as first found by a scientific expedition of the HMS Challenger in 1872-76. When dredging the sea floor, scientists onboard the British ship hauled up so-called manganese nodules, mineral rocks of roughly potato size and shape.

These nodules usually only appear at a water depth of 3,000-6,000 metres (9,000-18,000 feet), though occasionally they can be found in shallower waters. Visibly containing a high degree of metals, they were originally regarded a mineralogical curiosity.

Example of a “polymetallic nodule” harvested from the deep sea.

Today, we know that these nodules contain an extraordinarily high percentage of manganese and iron oxides, nickel, copper, cobalt, lithium, and various rare earth elements (REEs). Although they were initially named for their manganese content, they are nowadays mostly referred to as polymetallic nodules.

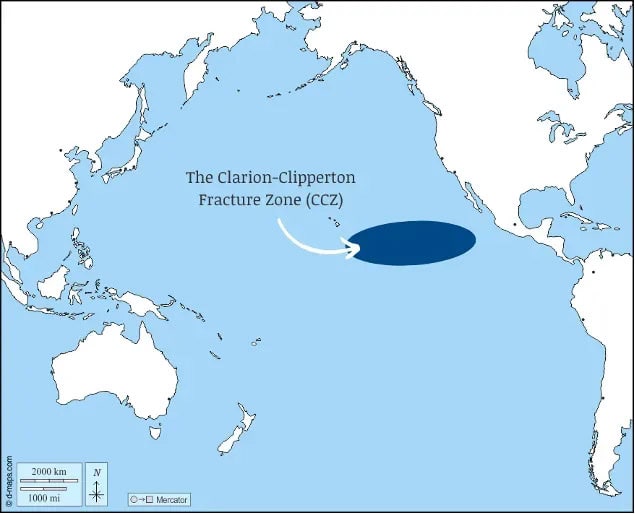

Much as they can be found in all oceans, the most extensive deposits of such nodules have so far been located in the Pacific Ocean, and especially in the Clarion-Clipperton zone that extends roughly from Hawaii in the West to Mexico in the East.

Initially exhibited in museums, these nodules became of broader interest after the Second World War. Knowledge of the oceans expanded, and 1965 saw the publication of “The Mineral Resources of the Sea” by John L. Mero. This groundbreaking book created an image of an easy-to-harvest, vast, and virtually unlimited resource, and allegedly fired the starting gun for a multitude of deep-sea mining projects across the world. The idea was that polymetallic nodules would only have to be picked up from the bottom of the ocean, rather than via “mining” in the conventional sense.

For some metals, it is estimated that the oceans contain several times the quantity that could be found on land. For example, while about 25m tonnes of cobalt resources exist on the Earth’s landmass (most of them in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Zambia), the total amount of cobalt identified under the sea is 120m tonnes.

It’s also striking just how concentrated those mineral deposits are. They contain nickel, manganese, cobalt, and copper in grades that don’t exist up on the surface.

MUST-watch: “The Truth about Deep Sea Mining“, Real Engineering (15-minute video).

During the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s, it was mostly companies from the US, West Germany, Japan, and Canada that tried to make deep-sea mining happen at an industrial scale. They formed several consortia, often multinational. The first successful pilot project managed to harvest 800 tonnes of manganese nodules from the ocean floor. The 1970s and up until 1982 marked the first golden period of deep-sea mining efforts.

Source: ResearchGate, May 2019 (paywalled).

Shifting prices and demand patterns for resources contributed to the subsequent demise of the sector, as did changing national priorities for environmental concerns. While some state-backed entities in Japan, India, South Korea, and China got more involved, overall the sector died a slow death during the 1980s.

It was revived in the 2000s by a single Canadian firm, Nautilus Minerals. The mining company had identified a large deposit of nodules off the coast of Papua New Guinea and negotiated a contract with the country’s government. It also managed to go public through a shell company and over time raised a total of USD 300m. However, the obstacles proved insurmountable yet again. Nautilus Minerals fell out with the Papua New Guinea government, filed for creditor protection in 2019 and went out of business.

After half a century of attempting to harvest these resources off the ocean floor, the sector had nothing much to show for. Cynics say that deep-sea mining in 2025 is no more advanced than the efforts of the 1970s.

One company from Canada, however, has set out to prove the naysayers wrong, having spent the last 13 years making the dream happen after all.

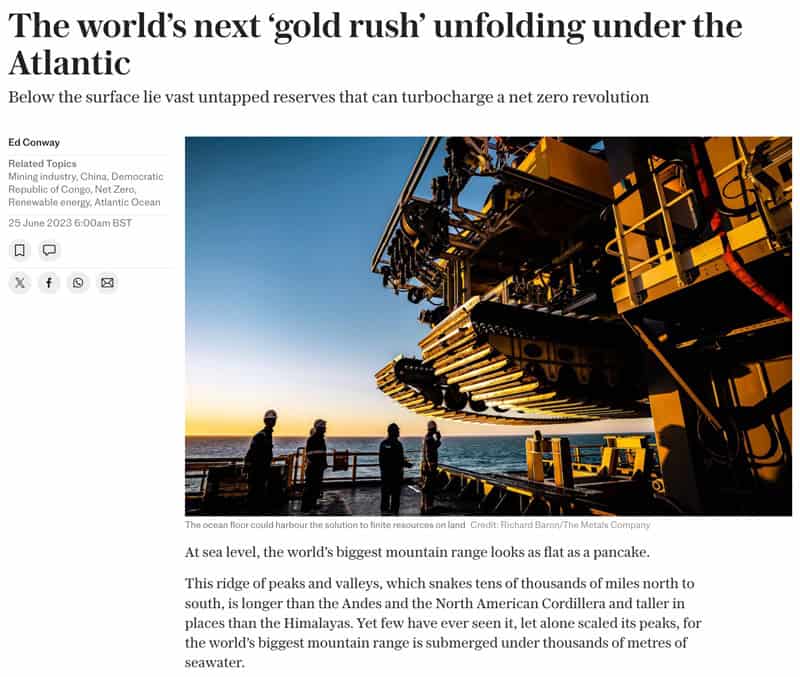

Source: The Telegraph, 25 June 2023.

The sector’s trailblazer

The Metals Company used to be called DeepGreen. Like many other mining ventures, it once tried to give itself a name that appeals to the real or perceived “green” credentials of mining metals from the bottom of the deep sea.

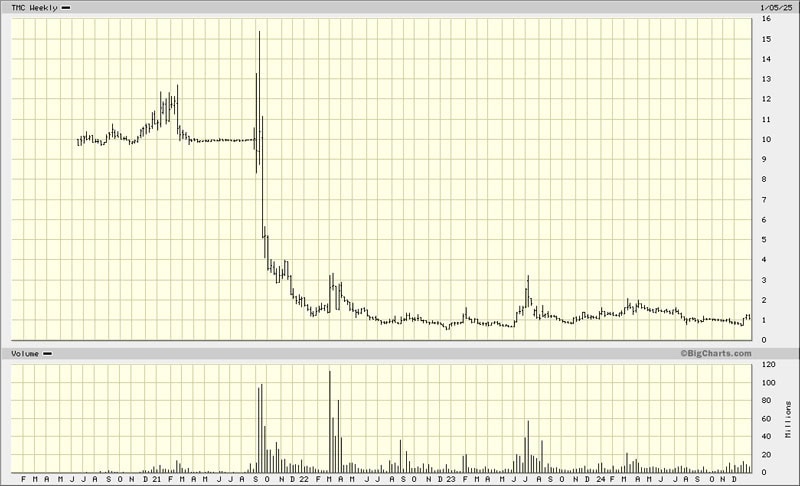

The company went public in late 2021 using a SPAC, like many other ventures at the time.

After trading as high as USD 15 when the SPAC transaction was first announced, the stock fell to USD 0.73 in December 2024. Over the past few weeks, it has shot up to USD 1.25, with noticeably large numbers of shares changing hands. At last count, it was trading at USD 1.09.

The Metals Company.

Why the sudden surge in interest?

The stock is back in play because some view it as a bet on Trump wanting to achieve resource autarky for the United States.

Besides, there is Elon Musk, who might feature in an important role.

It’s a highly speculative story, but that probably only attracts further interest from a particular type of investor.

The Metals Company may well turn out a bust for its shareholders. It is currently running low on cash, and whether the dream of deep-sea mining can ever be realised remains the subject of heated debates.

One thing is for sure, though.

If all the stars were indeed finally aligned for deep-sea mining, The Metals Company’s shareholders could be richly rewarded.

A company with ‘history’ – good and bad

Deep-sea mining in general, and The Metals Company in particular, come with controversy.

The company’s CEO, Gerard Barron, was a major investor in the failed efforts of Nautilus Minerals (though he sold a decade before it went bust). Following the SPAC listing of The Metals Company, two investors withheld USD 200m, and lawsuits followed. Greenpeace and a number of other NGOs love to portray Barron as the bogeyman.

On the plus side, the company he now leads succeeded in harvesting 3,000 tonnes of metallic nodules off the ocean floor. No other company in the sector had ever achieved a similar feat. The Metals Company also claims to have cracked the technological and environmental challenges: according to peer-reviewed research sponsored by the company, a kilogram of copper produced from polymetallic nodules generates a mere 29 kilograms of waste, as opposed to 460 kilograms of waste for copper produced in a conventional mine.

In August 2024, Dialogue Earth, a non-profit dedicated to environmental journalism, published an extensive feature on deep-sea mining, giving high marks to The Metals Company in at least some ways:

“The rapid advance of deep-sea mining in China is even more motivated by the progress made by North American and European companies, especially The Metals Company. This Canada-based outfit recovered 3,000 tonnes of nodules from the seafloor in test runs in 2022. ‘They took things to such an extent that it makes everyone believe [deep-sea mining] is technically feasible and economically profitable.'”

The Metals Company remains probably several years ahead of its competitors. It got there by not being afraid to be disruptive or demanding, as demonstrated with its 2021 application to the International Seabed Authority (ISA).

ISA is the regulatory body that is supposed to oversee mining on the ocean floor outside of the 200 nautical mile zone, i.e. on “high seas”. Its existence goes back to a seminal speech delivered by Arvid Pardo, a Maltese diplomat, at the United Nations General Assembly in 1967. Pardo spoke passionately about the sea as the origin of all life, and the need for a robust legal framework geared towards using the ocean resources in a peaceful way for the benefit of everyone.

His speech has been echoing through the ages – and, as some will say, for too long.

In 1996, ISA eventually emerged as a UN-backed body tasked with creating a framework that protects the oceans while allowing the responsible use of resources. Headquartered in Kingston, Jamaica, the ISA was never quite in a hurry. Mining the seabed seemed like a far-away dream, and ISA was the type of talking shop the UN is renowned for. As the Hakai Magazine put it in an 18 December 2024 article:

“For 25 years, deep-sea mining was a distant reality. Negotiations were easygoing, and those gathered in Jamaica would mingle at weekend retreats and dance parties.“

The lifestyle of the UN bureaucrats and their NGO bedfellows got a violent shock in 2021, when Barron’s company teamed up with the Pacific island nation Nauru. According to ISA regulations, mining the deep ocean was not going to be allowed until a framework had been agreed to. However, these regulations also contain a clause that if someone applied for a mining license and the ISA was not able to produce a regulatory framework within 24 months of the application being filed, the applicant could go ahead based on whatever draft framework was ready by then.

By filing such an application, Barron and Nauru forced ISA’s hand.

Up to now, there is still no such framework. The 24 months are up, and The Metals Company has the right to pull the trigger. Some observers expect the company to move ahead in mid-2025. According to latest news from the ISA, it aimed to have the regulatory framework in place by July 2025 – though some question how realistic that is.

Owning its own ocean vessel, The Metals Company would be ready to start mining the day after it files the paperwork.

Will it – won’t it?

That’s the trillion-dollar question investors are wondering about – all the more since the Trump landslide and the recent board appointment of an Elon Musk confidante.

A monster-sized opportunity

The figures relating to this opportunity are nothing but staggering.

The Metals Company is focused on exploiting an area that makes up about 4% of the world’s ocean. In this area alone, it expects recoverable nickel, copper, cobalt, and manganese to electrify every single vehicle in the US (that’s 280m vehicles).

It makes most other nickel deposits look small in comparison.