One Purpose. A Better Life.

🎁 Special Discount until 5th Jan. 2026

The Internet is brimming with resources that proclaim, “nearly everything you believed about investing is incorrect.” However, there are far fewer that aim to help you become a better investor by revealing that “much of what you think you know about yourself is inaccurate.” In this series of posts on the psychology of investing, I will take you through the journey of the biggest psychological flaws we suffer from that causes us to make dumb mistakes in investing. This series is part of a joint investor education initiative between Safal Niveshak and DSP Mutual Fund.

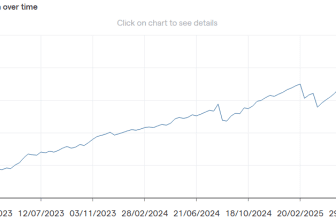

Peter Lynch ran the Magellan Fund from 1977 to 1990. For thirteen years, he was essentially a superhero of the stock market. Someone who invested $10,000 at the very beginning would have turned it into $280,000 by the time he retired. His average return was about 29% a year, which is like finding a magic lamp.

But here comes the part that sounds like a paradox so absurd it borders on a joke: most people who investedin his fund lost money. It doesn’t seem possible, does it? How can you lose money in a fund that wins that much?

The answer is simple and embarrassingly sad.

When the fund was doing great, people got excited and jumped at the top. But the moment the fund had a bad month or a rough quarter (which happens to all funds), they got scared and sold everything at the bottom.

To put it bluntly, investors were trying to use a twenty-year tool to fix a twenty-minute feeling. You could call it Time-Scale Confusion, which I’d argue is the number one reason why smart people do very dumb things with their money.

I have met countless investors over the past few years. In almost every conversation, I’ve noticed that most of the stress they feel doesn’t actually come from bad ideas. It comes from a mismatch in their heads— a fundamental disconnect between what they say they want and what they actually do. It’s like trying to measure how much a teenager has grown by checking their height every hour. If you do that, you’ll get frustrated and conclude that something’s wrong. But if you just wait a year, the growth is obvious.

In the world of investing, we are all guilty of checking our “height” every hour. We say we are “long-term investors,” which sounds sophisticated. We tell our friends we are building wealth for the next thirty years. But then, we check our phones at lunch and see that the market is down 2%. Suddenly, our thirty-year plan disappears. Our hearts start racing. We let a tiny bit of noise from a random Friday afternoon ruin a plan that was supposed to last for decades.

This is the first type of Time-Scale Confusion: judging a long-term dream with short-term emotions.

Now, like all the mistakes I’ve talked about in this series, it’s hard to blame ourselves for even the Time-Scale Confusion. Our brains, after all, were built for a different world, one with tigers and other immediate, tangible threats. Evolution didn’t give us a “wait and see” button; it gave us a “run or fight” button.

When you see your portfolio turn red, your brain thinks a tiger is in the room. It doesn’t care that the stock market has gone up for decades straight. It only cares that you are “losing” right this second, which feels like eternity. This is why people sell at the bottom. They aren’t trying to lose money; they are just trying to make the scary feeling go away.

Then comes the other side of this confusion, which is even more insidious. This is when we take a short-term gamble that goes wrong and try to pretend it was a long-term plan all along.

Let’s say you buy some hot stock because someone on social media said it was “the next big thing no one’s talking about.” You weren’t planning to hold it forever; you just wanted to make a quick return to buy a new laptop. But then, the stock crashes. You’re down 40%. Instead of admitting you made a bad bet and moving on, you suddenly start talking about the “future of the industry.” You tell yourself you’re a “value investor” now. You’ve turned a short-term mistake into a long-term anchor because your ego is too bruised to admit you were wrong.

This is how people end up holding onto bad investments for years. They are using a long-term excuse to hide a short-term failure.

We live in a world that makes this confusion worse every day. Thirty years ago, if you owned a piece of a company, you found out what it was worth by reading the newspaper once a week. There was a gap between you and the madness. Now, that gap is gone. You have a casino in your pocket. Your phone sends you alerts every second. This constant stream of information makes us feel like we have to constantly do something. It makes the present feel way more important than it actually is.

If you watch a movie frame by frame, you can’t tell what the story is. You just see flickering lights. But if you sit back and watch the whole two hours, the story makes sense.

Investing is the same. The daily price moves are just flickering lights. The long-term growth is the story. But our phones keep forcing us to stare at the pixels.

The reality is that the market is an efficient machine for taking money from people who are confused about time and giving it to people who aren’t. If you can stay calm when everyone else is acting like the sky is falling, you eventually get paid for that calmness.

It’s called a “risk premium,” but you can just think of it as a “patience tax.” You are being paid to not be a slave to your own lizard brain.

But being patient is boring. We are addicted to the “now,” and that addiction is incredibly expensive.

And it’s not just stocks. This behaviour is also rampant in mutual fund investing, which is supposed to be the “easy” way to invest. When you buy a mutual fund, you are basically hiring a professional to do the hard work for you. You are essentially telling them, “Here is my money, please grow it while I go live my life.” It’s a great system. But many people treat mutual funds like they are playing a video game. They look at which fund did the best last year and move all their money into it. Then, if that fund has a quiet six months, they get annoyed and switch to a different one.

This is like trying to get somewhere faster by constantly switching lanes in a traffic jam (which, by the way, isn’t unusual on Indian streets). Usually, the lane you just left starts moving the second you get out of it. You end up working twice as hard and getting there twice as slow.

The irony of mutual funds is that the people who do the best are often the ones who forget they even have an account. There is a famous (though possibly legendary) story about a studythat found the best-performing investors were the ones who were actually dead. Their accounts were just sitting there, untouched and un-fiddled with, for decades. Since they couldn’t check their phones or panic-sell during a recession, their money just sat there and compounded.

While we don’t have to be dead to be good investors, we should probably act a little more like it. We need to stop judging our investments by their “year-to-date” returns and start judging them by whether they are helping us reach a goal that is still ten or twenty years away.

If you find yourself getting anxious because the market is down, or if you’re tempted to buy something just because it’s “hot” right now, do yourself a favour and ask: “What is the time scale for this decision?”

If you are saving for a house in ten years, today’s red numbers don’t matter. They are literally irrelevant. And if you are tempted to hold onto a bad investment just to save your pride, remember that time is your most valuable asset. Don’t waste five years of it trying to prove you were right about a one-week trade.

Most of the pain in your portfolio is coming from the clock in your head being out of sync with the world. Fix the clock, and the rest usually takes care of itself.

Stop trying to win the sprint when you’re actually running a marathon. The finish line isn’t moving; only you are.

Disclaimer: This article is published as part of a joint investor education initiative between Safal Niveshak and DSP Mutual Fund. All Mutual fund investors have to go through a one-time KYC (Know Your Customer) process. Investors should deal only with Registered Mutual Funds (‘RMF’). For more info on KYC, RMF & procedure to lodge/ redress any complaints, visit dspim.com/IEID. Mutual Fund investments are subject to market risks, read all scheme related documents carefully.

One Purpose. A Better Life.

🎁 Special Discount until 5th Jan. 2026