New data from Thomson Reuters suggests that law firms now have fewer junior associates than before, as a proportion of the total fee earners. Meanwhile, ‘non-equity partners’, i.e. ‘very senior associates’ are growing relative to other ranks.

This raises several key questions. One is whether the pyramid is becoming more of a pillar? I.e. the steps between each fee earner group are smaller, so the model becomes less of a pyramid.

Another question is that if law firms proportionally have fewer junior lawyers, i.e. ‘associates’, than before, then is this a long-term trend that will continue to develop? Plus, will more use of genAI tools only accelerate this movement?

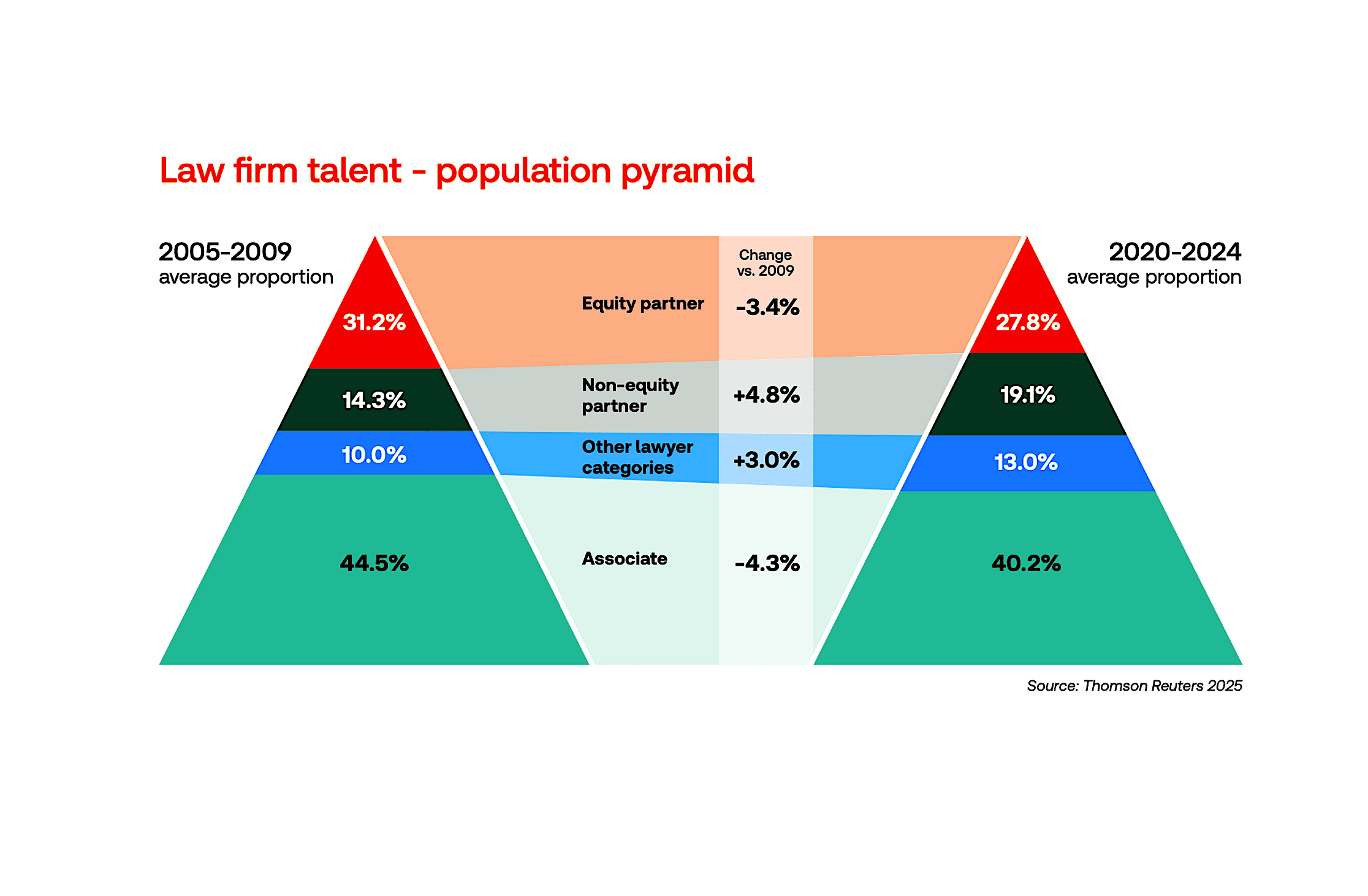

The data below from the TR Institute, and focused on US law firms, in some ways follows a trend we have had for some time, i.e. law firm partners are boosting their incomes by making the equity partner group – who literally ‘own the firm’ and hence get a direct share of the profits – ever smaller.

Smaller equity groups + larger firms with more fee earners + higher billable hour rates = very nice pay packets for the shareholder partners.

This movement is therefore to be expected, as owners of businesses always seek to maximise their profits. What is not so expected in a business model based on high leverage, i.e. the balance of legal workers to owners, is that the junior ‘associate’ group is shrinking relative to the total.

As seen in the chart, in 2005 to 2009 associates were 44.5% of a firm. Now, in 2020 to 2024 they are 40.2%. That may seem a small change, but in terms of the financial gearing of a legal business, this is significant.

Meanwhile, non-equity partners and ‘other lawyers’ in 2009 were 24.3% of the firm, i.e. lawyers the firm wanted to keep because of their expertise and experience, but perhaps don’t have the client relationships to bag a place in the equity. However, by 2024 this group had risen to 32.1%……that’s just under one-third of the whole firm!

If that trend continued over the next decade, then in time these ‘senior associates’ – as a non-equity partner is really just an older associate with a better title – plus the other senior roles such as counsel, or legal director, would eventually become equal to the number of junior associates.

So, back to the questions above: is the model changing? Is the model becoming a pillar?

Well, it depends on how you count it. If you are strictly focused on ownership vs leverage, then in fact leverage is increasing.

- 2009: 31.2 owners to 68.8 non-owners.

- 2024: 27.8 owners to 72.2 non-owners.

I.e. the pyramid is becoming even more extreme.

If you see a real separation between job titles, then it’s more of a pillar. But, is a non-equity partner really a ‘partner’? To this site the term is an oxymoron. A partner means you own part of the business….the clue is in the name. So, for this site at least, what this says is that law firms are now even more pyramidal, it’s just that they’re holding onto more of their older associate talent.

Older Associates

But why are they doing this?

You’ve probably heard the term: finders, minders, grinders. I.e. equity partners with key client relationships and/or are so well-regarded that clients flock to them; then the ‘middle management’ who are experienced and can run a deal team, but may not be the best client winners there; and then everyone else, who are often doing the bulk of the billable work.

Based on this data it seems that the minders group are becoming way more important. Maybe that’s because there is more ‘minding’ needed….? Or, alternatively, the minders are being kept on as highly-chargeable senior associates and being sweated the same way as the junior lawyers, but as they have higher hourly rates they can make a solid profit. I.e. they may be kept on not as minders, but rather as higher value fee-earners to become an extension to the main associate group.

It’s not clear yet which is the dominant reason.

Finally, the junior associates.

Why would the proportion of these key lawyers, who are fundamental to the business model, see a drop?

It’s tempting to say: ‘AI is taking their roles.’ But, this data is from 2020 to 2024, so that seems unlikely……yet.

What may be the answer is the point above, about holding onto more senior talent and leveraging them as what are in effect highly billable associates. I.e. as the minders group grows and grows, proportionally the junior associate group shrinks as a portion of the whole firm.

That does also perhaps suggest that clients and law firm bosses want more senior people actively on the billable work. After all, no firm needs hundreds of middle managers. What firms need most of all are those who do the work, and those who bring in the clients.

However, if we come back to the AI point. Looking ahead; as law firms bring more tech into workflows that were previously handled 100% in a pre-industrial way with tons of legal labour, then those workflows will need less associates.

BUT…..a law firm does not need to therefore reduce its junior ranks. It still needs them, and in fact, if the partners can find more work to feed the firm with its now higher throughput, then even with loads of AI doing multiple human tasks, there will still be a powerful need for plenty of junior lawyers.

That said, not all law firms may feel they can keep on absorbing more and more new clients to compensate for these changes and to feed the more efficient ‘legal machine’ they now run. In which case, fewer junior associates does seem likely in the future – but only as a proportion of the total lawyers at each firm, and only at those firms that can’t bring in enough additional business to adapt to the new conditions.

The legal market as a whole looks set to grow and grow. So, this is not an ‘end of lawyers’ scenario, but it may be a ‘we don’t need so many junior lawyers per firm’ scenario at some legal businesses – although not all.

To conclude, we don’t know yet which way things will go. By 2030 we will have a much better picture. But, one thing is for sure: the traditional legal production model is changing, and that’s even before the full impact of legal AI arrives.

—

Note: the data comes from the recent TR / Georgetown Law study on the US legal market.