Climate Inaction is an Affordability Problem

The costs of climate change, especially those from climate-related natural disasters, are already substantial for US households.

This post is authored by UCLA Law’s Kimberly A. Clausing along with guest contributors Christopher R. Knittel and Catherine Wolfram.

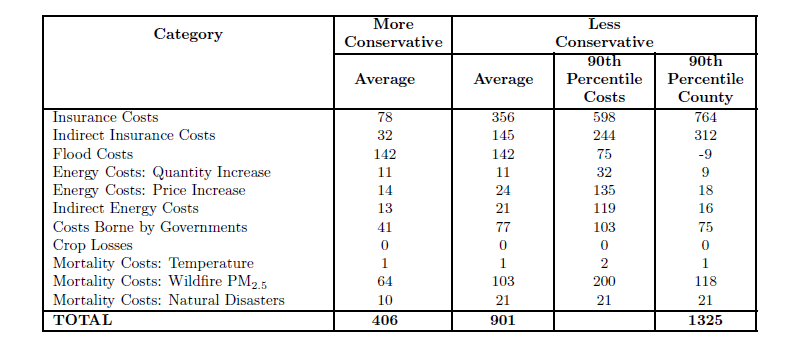

Many of us have seen large increases in our homeowner’s insurance premia in recent years – yet another cost increase that is putting strain on homeowners and driving up rents. In forthcoming work for the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (working paper here), we detail the affordability impacts of climate change and show that it is already imposing substantial costs on US households, about $900 each year in recent years. Costs are far higher in regions of the country that have faced natural disasters such as fires and hurricanes.

The paper examines some, but not all, of the current costs of climate change. For example, we examine how natural disasters impact housing costs through multiple channels: by raising insurance premia for housing, by generating uninsured losses due to floods, and by increasing government disaster relief costs, which are ultimately borne by taxpayers. These costs are significant, averaging over $700 for a typical household. There are also important health consequences from natural disasters, generating average household harms that exceed $100 per year.

In contrast to the effects of natural disasters, the consequences of higher temperatures are more benign. We find that increased energy costs for US households average about $30, and the net effects of rising temperatures on mortality are minimal, since increased deaths due to heat are offset by fewer deaths due to cold. Further, crop damages from extreme temperatures have been minimal as well, since higher temperatures have not been a significant factor in key agricultural regions of the United States.

Estimated Annual Average Household Costs by Category

One key challenge of this research is quantifying the fraction of natural disasters that are due to climate change. To allow for uncertainty, we also calculate a “more conservative” estimate that attributes a smaller fraction of increased natural disasters to climate change; under this scenario, average household costs are about $400, about $290 of which is due to effects of disasters on home insurance prices, uninsured flood costs, and government relief efforts; costs due to the mortality consequences of natural disasters are about $75.

One overarching lesson of our investigation is that the impact of natural disasters is far more consequential for US households than that of increased heat. To some extent, this is unsurprising, since adaptation through air conditioning may limit the consequences of higher temperatures, whereas the costs associated with unpredictable weather are more difficult to avoid.

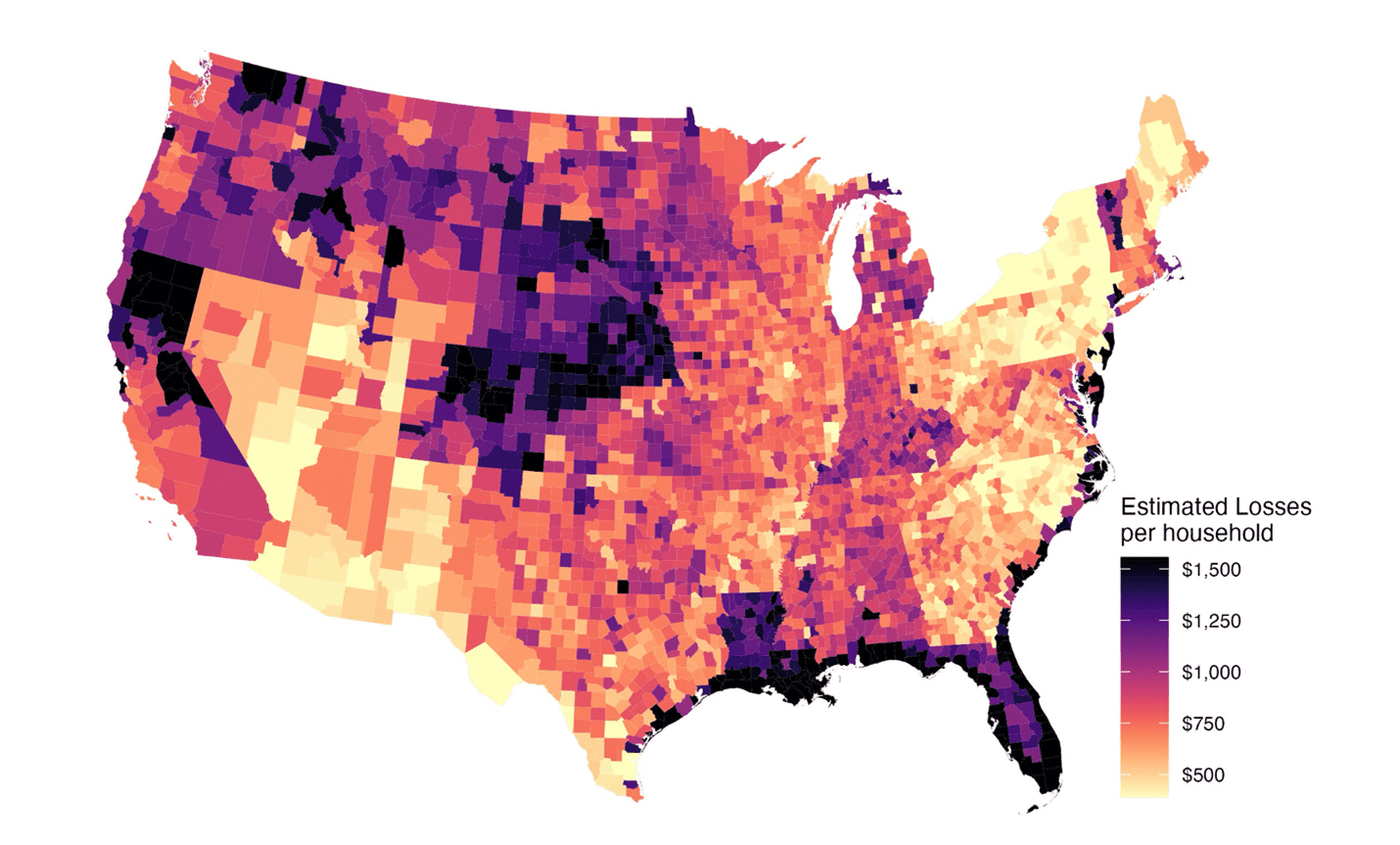

A second key lesson from our research is that climate change has disparate impacts. Geography is an essential factor; areas subject to more wildfires and extreme weather events – such as the rural west and the Gulf coast – face disproportionate costs. Households in the 90th percentile of climate costs experience about 50 percent higher-than-average US household costs. Further, many climate costs are regressive, impacting lower-income households more than higher-income households; the lowest income decile households pay more than double the damages (as a proportion of their income) relative to top income decile households. In some rural and coastal counties, household costs exceed $1,300 a year — effectively a ‘climate tax’ on those least able to pay.

Geographic Inequities from Increased Climate Change Costs

There are several key policy implications from this research. First, the costs of climate inaction are often greater than the costs of well-designed climate action for US households. For example, the increased costs to US households from more aggressive climate policy (see Bistline et al. 2025) is typically smaller than the costs of climate inaction demonstrated here. Second, the costs of climate inaction are more regressive that well-designed climate policies. Green et al. 2025 demonstrate climate policy can easily be designed to mitigate or eliminate inequalities across income groups or geography, whereas climate inaction has inherently disparate effects. Third, climate adaptation is important; federal, state, and local governments should be more active in addressing natural disaster risks.

The costs of climate inaction are substantial, aggregating to more than $110 billion per year in our main estimate. Still, several caveats are worth bearing in mind. First, we have only analyzed the United States, and effects in other countries may have different patterns. Second, climate action is a global collective action problem. More active U.S. climate policy would help mitigate the effects of climate change for people around the world, just as action abroad helps mitigate the effects of climate change for US households. This suggests the importance of international coordination and collaboration.

Third, there are important threshold effects and nonlinearities that impact these calculations. The costs of climate inaction, including the effects of increased natural disasters, will rise steeply if average temperatures continue rising as forecasted. Finally, there are both important omissions and important uncertainties in these estimates, described further in the paper, suggesting a robust agenda for future research.

This post is authored by UCLA Law’s Kimberly A. Clausing along with guest contributors Christopher R. Knittel and Catherine Wolfram.