INTRODUCTION

Crohn’s disease (CD) has been increasing in incidence and prevalence worldwide. At the same time, the number of therapeutic options is rapidly increasing. The purpose of this guideline was to review CD clinical features and natural history, diagnostics, and therapeutic interventions.

To prepare this guideline, literature searches on the different areas were conducted using Ovid MEDLINE from 1946 to 2025, EMBASE from 1988 to 2025, and SCOPUS from 1980 to 2025. The major terms that were searched were CD, inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), regional ileitis, and regional enteritis. These were translated into EMTREE controlled vocabulary as enteritis and CD. The remainder of the search included key words related to the subject area that included clinical features, natural history, diagnosis, biomarkers, treatment, and therapy. For each of the therapeutic sections, key words included the individual drug names. The results used for analysis were limited to primary clinical trials, meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and prior guidelines. Where there were limited data, observational data were used. In areas where data were limited, and Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) was not feasible, key concept statements were developed from expert opinion of the literature.

Where possible, the GRADE process was used to evaluate the quality of supporting evidence. A strong recommendation is made when the benefits or desirable effects of an intervention clearly outweigh the negatives or undesirable effects and/or the result of no action. The term conditional is used when some uncertainty remains regarding the balance of benefits and potential harms, either because of low-quality evidence or because of a suggested balance between desirable and undesirable effects. The quality of the evidence is graded from high to low, where high-quality evidence indicates that the authors are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate-quality evidence is associated with moderate confidence in the effect estimate, although further research would be likely to have an impact on the confidence of the estimate. Low-quality evidence indicates limited confidence in the estimate, and thus, the true effect could differ from the estimate of the effect. Very low-quality evidence indicates very little confidence in the effect estimate and that the true effect may be substantially different than the estimate of effect (1–3).

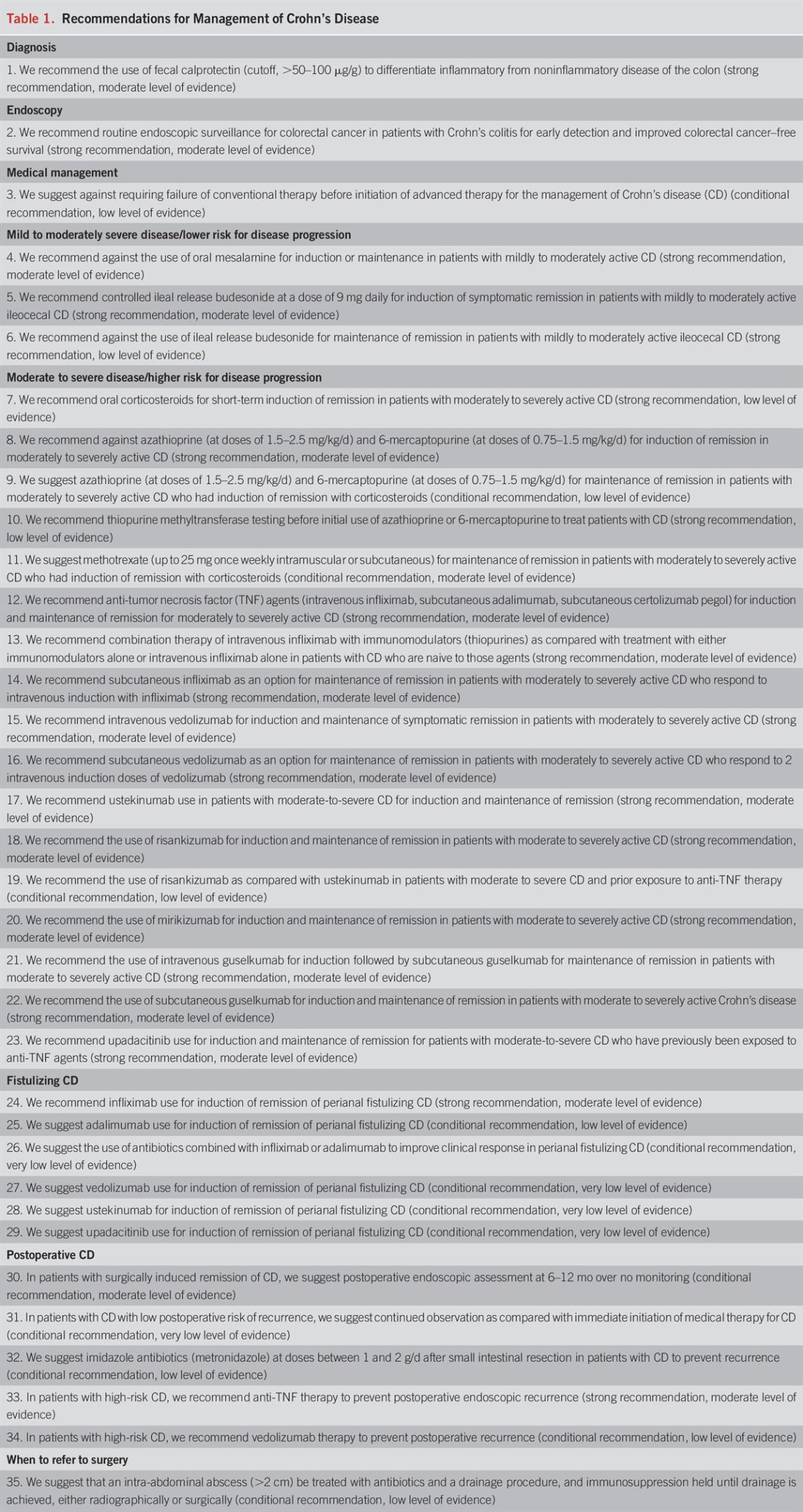

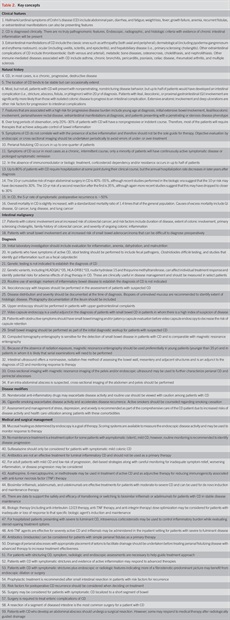

We preferentially used meta-analyses or systematic reviews when available, followed by clinical trials and retrospective cohort studies. The GRADE recommendations statements from this guideline are in Table 1. Summary Key Concept statements, which do not have associated evidence-based ratings, are in Table 2.

Recommendations for Management of Crohn’s Disease

Key concepts

CLINICAL FEATURES

Key concept

The most common symptom of CD is chronic diarrhea, but some patients may not experience this symptom (4). Abdominal pain, often localized to the right lower quadrant of the abdomen and worsened postprandially, is common. Fatigue is also a very prevalent symptom in CD and is believed to arise from several factors including inflammation itself, anemia, or various vitamin and mineral deficiencies. Some patients will present with constitutional signs or symptoms including fever, weight loss, or, in the case of younger patients, growth failure.

Key concept

The clinician must integrate multiple streams of information, including history and physical, laboratory tests, endoscopy results, pathology findings, and radiographic tests, to arrive at a clinical diagnosis of CD. In general, it is the presence of chronic intestinal inflammation that solidifies a diagnosis of CD. Distinguishing CD from ulcerative colitis (UC) can be challenging when inflammation is confined to the colon, but clues to the diagnosis include discontinuous involvement with skip areas, sparing of the rectum, deep/linear/serpiginous ulcers of the colon, strictures, fistulas, or granulomatous inflammation. Granulomas are present on biopsy in only a minority of patients. The presence of ileitis in a patient with extensive colitis (backwash ileitis) can also make determination of the IBD subtype challenging.

Key concept

A systematic review of population-based cohort studies of adult patients with CD identified an increased risk of bone fractures (30%–40% elevation in risk) and thromboembolism (3-fold higher risk) (5). A variety of extraintestinal manifestations, including PSC, ankylosing spondylitis, uveitis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and erythema nodosum, have been observed in patients with CD. Moreover, there are weak associations between CD and other immune-mediated conditions, such as asthma, psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and multiple sclerosis.

NATURAL HISTORY

Key concept

The chronic intestinal inflammation that occurs in CD can lead to the development over time of intestinal complications such as strictures, fistulas, and abscesses. These complications can lead to inhibition of intestinal function or to surgery that itself can result in some morbidity and loss of intestinal function. A scoring system, the Léman index, has been created to quantify the degree of bowel damage incurred by intestinal complications and subsequent surgery (6). This index has been shown to be reproducible and internally consistent, and median index scores rise with disease duration (7). In a population-based cohort study from Olmsted County, Minnesota, of 147 patients with CD who had undergone at least 1 bowel resection (median follow-up per patient, 13.6 years), the median cumulative length of bowel resected was 64 cm, and the median rate of bowel resection was 4.2 cm annually (8).

Key concept

Population-based studies from Norway and Minnesota suggest that CD presents with ileal, ileocolonic, or colonic disease in roughly one-third of patients each, with up to a quarter also having upper gastrointestinal (GI) involvement and that only a small minority of patients (6%–14%) will have a change in disease location over time (9–11).

Key concepts

Multiple population-based cohorts of CD have demonstrated that most of the patients (between 56% and 81%) have inflammatory disease behavior at diagnosis, whereas between 5% and 25% each present with stricturing or penetrating disease behavior (10). A population-based study from Olmsted County showed that the cumulative risk of developing an intestinal complication among those presenting with inflammatory behavior was 51% at 20 years after diagnosis (12). Multivariate analysis demonstrated that ileal, ileocolonic, or upper GI involvement, relative to colonic involvement, was significantly associated with faster time to the development of intestinal complications. Colonic disease was also found to be protective against the progression to complications in the multicentric European Epi-IBD cohort (13). Additional risk factors associated with a more severe CD course include younger age at diagnosis, extensive luminal involvement, perianal disease, and severe rectal disease (14,15). Awareness of these clinical features at the time of presentation is essential for early initiation of medical and/or surgical therapies.

Key concepts

Several studies illustrate the disconnect between symptoms and inflammation. For example, in a prospective study of 142 patients treated with prednisolone for 3–7 weeks, there was no correlation between Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) scores and Crohn’s Disease Endoscopic Index of Severity scores (16). In a cross-sectional study of 164 patients with CD, not only did CDAI scores not correlate with Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease (SES-CD) scores, they also did not correlate with serum C-reactive protein (CRP), fecal calprotectin (FC), and fecal lactoferrin (17).

Key concept

In population-based cohorts, the frequency of perianal fistulas is between 10% and 26%, and the cumulative risk was 26% at 20 years after diagnosis in 1 cohort (10,18,19). Perianal disease at diagnosis may indicate a more severe clinical course of CD. More recent population-based studies suggest that the cumulative incidence of perianal disease may be decreasing (20). A recent systematic review of population-based cohorts estimated the prevalence of perianal involvement in CD to be 18.7% and that the 10-year progression to perianal CD was 18.9% (21).

The onset of perianal CD may occur before the onset of luminal CD. In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, it was reported that 3.8% (based on 5 studies, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.9%–7.3%) of patients with CD developed perianal disease before luminal CD diagnosis (21). In a population cohort study form New Zealand which evaluated 715 patients with CD over with median follow-up after CD diagnosis was 9 years, it was observed that perianal lesions can be the first manifestation preceding the diagnosis of CD by > 6 months in 17% patients; in 27% perianal disease presents from 6 months before to 6 months after the diagnosis of CD, whereas perianal disease is first observed >6 months after CD diagnosis in the remaining 56% (22). However, it remains unclear whether all patients in this study underwent a thorough assessment for luminal disease by means of cross-sectional imaging of the abdomen or capsule endoscopy.

Key concept

A population-based study from Olmsted County, Minnesota, modeled the lifetime course of CD in various disease states using a Markov model; the model was unique in that the transition probabilities between disease states were derived by mapping disease states to the actual chronological history of each patient (23). Over the lifetime disease course, a representative patient spent 24% of the duration of their disease in a state of medical remission, 27% in mild disease, 1% in severe drug-responsive disease, 4% in severe drug-dependent disease, 2% in severe drug-refractory disease, 1% in surgery, and 41% in postsurgical remission. In the 1962–1987 Copenhagen County cohort, within the first year after diagnosis, the proportions of patients with high activity, low activity, and clinical remission were 80%, 15%, and 5%, respectively (24). However, after the first year through 25 years, a decreasing proportion of high activity (30%), increasing proportion of remission (55%), and stable proportion of mild activity (15%) were observed.

Key concept

Population-based studies from Denmark and Minnesota suggest that between 43% and 56% of patients with CD received corticosteroids in the prebiologic era and that over half of these patients were steroid-dependent, steroid-refractory, or required surgical resection within the subsequent year (25,26). In a study from Minnesota in the biologic era, 1-year outcomes after the use of corticosteroids included prolonged remission in 60%, steroid dependency in only 21%, and resection in 19% (27).

Key concept

An older Copenhagen County study suggested that 83% of patients were hospitalized within 1 year of diagnosis, and the annual rate of hospitalization thereafter was approximately 20% (25). Up to 70% of Olmsted County patients were hospitalized at least once, and the cumulative risk of hospitalization in the prebiologic era was 62% at 10 years. The annual rate of hospitalization was highest in the first year after diagnosis (19). A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based cohorts of CD estimated a cumulative risk of hospitalization of 44%–49% at 5 years and up to 59%–72% at 10 years (28).

Key concept

In a systematic review of 30 publications examining major abdominal surgical risk in CD, the cumulative incidence of surgery was 46.6% at 10 years and that this risk was reported to be lower, under 40%, among patients who had been diagnosed after 1980 (29). Another systematic review examined the risk of a second resection among those patients with CD who had undergone a first resection, and this was estimated to be 35% at 10 years overall, but significantly lower among those patients diagnosed after 1980 (30). A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based cohorts estimated that the cumulative incidence of surgery in CD had decreased in relative terms by 45%–50% in the postbiologic era (for example, the 10-year risk of surgery decreased from 46.5% before 2000 to 26.2% after 2000) (31).

Key concept

Among patients with CD who undergo major abdominal surgery, the 5-year cumulative risk of clinical recurrence is 40%–50% (32,33). The risk of endoscopic recurrence approaches 90%. Risk factors for recurrent CD postoperatively include cigarette smoking, shorter duration of disease before operation, more than 1 resection, and penetrating complications. In a systematic review of 37 studies (mixture of cohort studies and randomized trials), with a median follow-up ranging from 72 to 162 weeks, the pooled crude endoscopic recurrence rate was 52%–57%, and the pooled crude clinical recurrence rate was 25%–31% (34).

Key concept

A 2007 meta-analysis of 13 studies of CD mortality yielded a pooled standardized mortality ratio of 1.5 (35). There was a nonsignificant trend for decreased mortality in more recent studies. In a 2013 meta-analysis, the pooled standardized mortality ratio for CD was 1.46 and slightly lower at 1.38 when restricted to population-based and inception studies. This study confirmed a previously noted association between CD and increased mortality from respiratory disease (36). Several studies have demonstrated an association between current use of corticosteroids and increased mortality in CD (37,38). A large Danish study showed no change in relative mortality in CD between 1982 and 2010, roughly 50% higher than the general population (39). Mortality was 25% higher than expected among patients with CD from Olmsted County, and this was largely driven by those diagnosed before 1980 (40).

INTESTINAL MALIGNANCY

Key concept

Patients with CD with colitis are at increased risk of CRC (41). Similar to UC, risk factors for CRC include duration of CD, PSC, and family history of CRC.

Key concept

The relative risk (RR) of small bowel adenocarcinoma in patients with CD is markedly elevated (at least 18-fold), although the absolute risk remains low, in the order of 0.3 cases per 1,000 patient-years (42). The increased risk is believed to arise from longstanding chronic inflammation.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of CD is based on a combination of clinical presentation and endoscopic, radiologic, histologic, and pathologic findings that demonstrate some degree of focal, asymmetric, transmural granulomatous inflammation of the luminal GI tract. Laboratory testing is complementary in assessing disease severity and complications of disease. There is no single laboratory test that can make an unequivocal diagnosis of CD. The sequence of testing is dependent on presenting clinical features.

Symptom assessment

Evaluation of clinical disease activity should include assessment of stool frequency and consistency, the presence of abdominal pain, systemic signs of inflammation (e.g., fever, weight loss, tachycardia, and anemia), and extraintestinal manifestations of CD. In addition, other clinical features may include obstructive symptoms, food aversion, and dietary changes. Rectal pain or defecatory issues may be associated with perianal CD.

However, other conditions may present with symptoms indistinguishable from active luminal CD. Therefore, an essential part of clinical evaluation is to determine whether presenting symptoms are due to CD vs other conditions, such as bile salt diarrhea, intestinal infection, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (especially for patients with an ileocolonic resection or known intestinal strictures), bypass from a fistula, dietary intolerances, disorders of the gut-brain interaction, anorectal sphincter dysfunction, medication-related adverse event, or potential mimickers of CD (e.g., endometriosis, tuberculosis). When diagnostic uncertainty is present because of clinical symptoms, it is recommended to confirm disease activity through imaging and/or endoscopic assessments. In individuals without any observable mucosal inflammation or ulceration, consideration should be given to the potential differential diagnostic possibilities.

Routine laboratory investigation

Key concepts

Recommendation

Patients presenting with suspected CD often will show laboratory evidence of inflammatory activity. Anemia and an elevated platelet count are the most common changes seen in the complete blood count (43,44). CRP is an acute phase reactant produced by the liver in the presence of inflammation. It is elevated in a subset of patients with CD. It has a short half-life of 19 hours. Because of its short half-life, serum concentrations decrease quickly, making CRP a useful marker to detect and monitor inflammation (see later section) (45,46). Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) may be useful in an individual patient, but it is not predictive of IBD and does not discriminate patients with IBD from those with IBS or healthy controls (47). Up to 40% of patients with IBD with mild inflammation may have a normal CRP and ESR, limiting the usefulness of these markers in monitoring some patients (48). Signs and symptoms of bowel inflammation related to IBD overlap with those of infectious enteritis and colitis. Stool studies for fecal pathogens and Clostridioides difficile will help direct diagnosis and management. FC is a calcium-binding protein derived from neutrophils and plays a role in the regulation of inflammation. It is a sensitive marker of intestinal inflammation. Other proteins in the stool derived from neutrophils include lactoferrin, lysozyme, and elastase. In an inflamed bowel, these proteins may be released into the stool. Measurements of FC serve as noninvasive markers of intestinal inflammation and may be useful in differentiating patients with IBD from those with irritable bowel syndrome (49). A recent meta-analysis found that a FC level of 50 μg/g had a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 72% in distinguishing IBD from functional GI disease (50). Other studies suggest cutoff values ranging from 50 to 100 μg/g (51,52). Fecal markers may also be useful in monitoring disease activity and response to treatment (53).

Genetic testing

Key concepts

CD is a heterogeneous disease with complex interactions between genetics, environmental exposures, and the intestinal microbiome. To date, there are over 200 genetic loci associated with IBD and greater than 71 CD susceptibility loci that have been identified through large-scale genome-wide association studies (54–56). As more genetically diverse populations are studied, this is likely to expand. Examples of single-nucleotide polymorphisms that confer susceptibility to CD include sequences in the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2 (NOD2) gene, the interleukin (IL)-23 receptor gene, and the autophagy-related 16-like 1 gene (57). These genes play a role in innate immunity and regulation of the epithelial barrier (58). These susceptibility variants are biologically important in understanding the pathophysiology of CD, but there is no single variant that has a high enough frequency in the CD population to make it diagnostically useful. There is significant variation in the prevalence of susceptibility genes between various racial/ethnic groups—for example, NOD2 and IL23R variants are very uncommon in East Asian populations (54). There are genetic variants that are associated with disease phenotype. NOD2 variants are predictors of a more complicated disease behavior including ileal involvement, stenosis, and penetrating disease behaviors and the need for surgery (59). These variants are also associated with early disease onset (60). IL-12B variants are associated with the need for early surgery (61). NOD2 testing is commercially available for 3 of the most common variants seen in CD. Although identification of these variants may identify patients who are likely to have more aggressive CD, this laboratory test has not been routinely used clinically and remains a research tool. Ultimately, we may be able to use genetic testing to characterize patient’s disease behavior and guide early therapy (62). Other potential uses of genetic testing include predicting both responses to and adverse events related to drug therapy for IBD. NUDT15 and TPMT variants are associated with thiopurine-induced leukopenia (63). The HLADQA1*05 and the HLA-DRB1*03 haplotypes have been associated with increasing immunogenicity to tumor necrosis factor (TNF) antagonists (64–67).

Serologic markers of IBD

Key concept

Because of the heterogeneous nature of IBD, there has been extensive research directed toward finding immunologic markers that would assist in disease diagnosis. These studies have focused on antibodies to microbial antigens and autoantibodies (68–73). Anti-glycan antibodies are more prevalent in CD than in UC but have a low sensitivity, making their use in diagnosis less helpful (73). Tests have been developed that use a combination of serologic, genetic, and inflammatory markers to try to improve diagnostic efficacy; however, this combination of markers has not improved serology measurements usefulness as a screening tool (74).

Endoscopy: colonoscopy

Key concepts

Colonoscopy with intubation of the terminal ileum and biopsy of endoscopically involved and uninvolved mucosa are recommended as part of the initial evaluation of patients with suspected IBD. Over 80% of patients with IBD will have mucosal involvement within the reach of the colonoscope. Ileal intubation rates are as high as 80%–97% in patients in whom the cecum is reached (75). Computed tomography enterography (CTE) and magnetic resonance enterography (MRE) examinations of the terminal ileum may both over- and under-represent disease of the ileum but are useful for detection of more proximal disease. Direct evaluation of the ileum will complement radiographic findings in the diagnosis of CD. Mucosal changes suggestive of CD include mucosal nodularity, edema, ulcerations, friability, and stenosis (75–77). Classical granulomatous inflammation is seen in a minority of patients (up to 33%) with CD and is helpful but not required for diagnosis. Disease distribution of endoscopic and histologic findings is important to document at the time of diagnosis because this has implications on screening for CRC, disease prognosis, and in the future—affect therapeutic decision-making. Attempts to quantify the distribution and severity of mucosal involvement of the colon and the ileum in patients with CD have led to the development of multiple endoscopic scoring systems, of which the SES-CD is the simplest to use (78,79). Studies using central readers have shown excellent intrarater and inter-rater reliability (80). This tool is available in many endoscopic documentation programs and may allow for serial assessment of the mucosa during therapeutic interventions in CD (see later section).

Colonoscopy for CRC surveillance

Recommendation

Most surveillance guidelines have been adapted from UC practice guidelines. Recently, a study of 23,751 colonoscopies in patients with IBD demonstrated that the rate of progression of dysplasia was similar in patients with UC and CD. These findings support that surveillance strategies should be similar for both UC and CD (81). Surveillance colonoscopy is suggested for patients who have a minimum of 8 years of disease with involvement of more than 30% of their colon. The risk of neoplasia in Crohn’s colitis increases with both the duration and the extent of disease (82). PSC and diagnosis of CD before the age of 40 years are also associated with increased risk of both CRC incidence and mortality (83,84). CRC surveillance has been shown to increase detection of early CRC and lead to decreased CRC mortality (85). Individuals with PSC should initiate surveillance colonoscopy at the time of their diagnosis regardless of disease distribution. The incidence of small bowel cancer is also increased in CD compared with the non-IBD population; however, routine surveillance is not currently recommended. There should be a high index of suspicion for small bowel cancer in a stable patient with small bowel CD who has an abrupt change in symptoms.

Key concept

CD of the upper GI tract is often underestimated, with most studies in adults suggesting that the range is 0.3%–5% (86,87). However, data from prospective studies suggest up to 16% of patients with CD have endoscopic and histologic changes of upper GI CD with only 37% of patients exhibiting upper GI symptoms at the time of evaluation (88). Routine endoscopic evaluation in asymptomatic patients with CD is associated with mild endoscopically visible inflammation in up to 64% of patients and histologic inflammation in up to 70% of patients (89). These studies have been performed predominantly in children. Despite these findings, there does not seem to be any clinical significance related to these mild changes (90). Endoscopic features suggestive of CD includes mucosal nodularity, ulceration (both aphthous and linear ulcerations), antral thickening, and duodenal strictures (91). Histologic changes include granulomatous inflammation, focal cryptitis of the duodenum, and focally enhanced gastritis (88,92).

Video capsule endoscopy

Key concepts

Small bowel capsule endoscopy allows for direct visualization of the mucosa of the small intestine. Isolated small bowel involvement may be seen in up to 30% of patients with CD, making it more challenging to diagnose with routine small bowel imaging techniques (93). Several meta-analyses have examined the diagnostic yield of capsule endoscopy in the evaluation of patients with suspected CD. Capsule endoscopy is superior to small bowel barium studies, CTE, and ileocolonoscopy in patients with suspected CD, with incremental yield of diagnosis of 32%, 47%, and 22%, respectively (93). Capsules with a panoramic 344o viewing area may improve complete mucosal visualization in patients with suspected CD (94). However, some studies have questioned the specificity of capsule endoscopy findings for CD, and to date, there is no consensus as to exactly which capsule endoscopy findings constitute a diagnosis of CD (95). The Lewis score is a scoring system based on the evaluation of 3 endoscopic parameters: villous appearance, ulcers, and strictures. The scoring system is incorporated into the software platform of some endoscopy capsules and assists in the quantification of small bowel inflammatory burden and diagnosis of CD (96). Capsule endoscopy has a high negative predictive value of 96% (97). The capsule retention rate in patients with suspected CD is 0%–5.4% and higher in those with known CD (98). Use of a patency capsule or small bowel imaging before video capsule endoscopy will reduce the risk of retention of the standard video capsule (99–102). A failed patency capsule study has also been shown to be associated with worse long-term clinical outcomes as compared with successful passage of the PC regardless of CD phenotype (103). Capsule endoscopy may also identify a site for directed biopsy to obtain tissue to establish a diagnosis of CD.

Imaging studies

Key concepts

The small bowel is one of the most common areas affected by inflammation in patients with CD. Much of the inflammation is beyond the reach of standard endoscopic evaluation. In up to 50% of patients with active small bowel disease, inflammation may skip the terminal ileum or be intramural and not detected by ileocolonoscopy (104). Complications of CD such as stricturing disease and enteric fistulas are best identified using small bowel imaging techniques. CTE has a reported sensitivity as high as 90% in detecting lesions associated with CD (95,105). The sensitivity for detecting active small bowel CD in 1 comparison study was only 65% with small bowel follow-through compared with 83% with CTE (95). In studies comparing capsule endoscopy with small bowel follow-through, there have been instances of patients with a normal small bowel follow-through showing both mucosal disease (20%) and stricturing disease (6%) on a capsule endoscopy (106). CTE features such as mucosal enhancement, mesenteric hypervascularity, and mesenteric fat stranding are all suggestive of active inflammation (107). MRE has similar sensitivity to CTE with wall enhancement, mucosal lesions, and T2 hypersensitivity as suggestive of intestinal inflammation (108). Studies with CT and MRE in patients with negative ileoscopy and biopsy that show unequivocal inflammation are associated with disease progression in 67% of patients (109). Inflammation scoring systems have been developed to provide quantification of the degree of inflammation. This may allow for assessment of treatment effects in serial examinations (110). Improvement in radiologic parameters for CTE and MRE with medical therapy is associated with a better clinical outcome regarding hospitalization, surgery, and corticosteroid use in patients with small bowel CD (111). The need for sequential imaging exams may be higher in young patients, patients with upper GI disease, those with penetrating disease, and patients who require steroids, biologics, and surgery. The need for repeated CTE studies over time leads to levels of diagnostic radiation exposure that theoretically might increase cancer risk (112,113). In these patients, MRE is preferred. Techniques to reduce dose of radiation exposure during diagnostic CT scanning have been implemented and currently being refined using changes in both software and hardware to maintain image quality with decreased radiation dosing. How this will alter the use of CTE is not known (114). IUS has been used in the management of CD in Europe for over a decade. Recently, there has been growing interest in its use and training in the United Sates. IUS enables real-time imaging to the intestinal wall, mesentery, and adjacent lymph nodes. Regarding diagnosis, point-of-care IUS can help identify bowel wall changes, potentially facilitating early referral for definitive diagnostic studies (115).

Key concept

Approximately 25% of patients with CD will develop a perirectal complication of their disease including fistula formation and/or perirectal abscess. With standard medical therapy, there is a high relapse rate of fistulous drainage. Imaging of the perianal area allows for identification of disease that requires surgical intervention to help with healing as well identify and classify all of the disease that is present premedical and postmedical therapy (116). Comparison studies have shown EUS to have greater than 90% accuracy in diagnosis of perianal fistulizing disease (117). Serial EUS examinations may be used to help guide therapeutic intervention in patients with fistulizing CD including seton removal and discontinuation of medical therapy (118,119). Magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis has comparable accuracy (116,120). Scoring systems looking at disease activity and fibrosis have been developed and play a role in predicting treatment outcomes in perianal fistulizing disease (121).

Key concept

CTE and MRE both have an accuracy of greater than 90% in the detection of abscesses pre-operatively (122). Recently studies have shown that IUS is useful and accurate for the diagnosis of intra-abdominal complications of CD and can be used as a noninvasive, point-of-care evaluation in the appropriate clinical setting (123). CT can be used to help direct abscess drainage preoperatively which may lead to a lower rate of postdrainage complications (124).

Disease modifiers

Key concept

NSAIDs may cause damage to the small intestine distal to the duodenum resulting in mucosal ulcerations, erosions, and webs. Mucosal permeability is increased with NSAID therapy, leading to increased exposure to luminal toxins and antigens (125). In a comparison study of acetaminophen, naproxen, nabumetone, nimesulide, and aspirin, there was a 17%–28% relapse rate of quiescent IBD within 9 days of therapy with the nonselective NSAIDs (naproxen and nabumetone) (126). Recent NSAID use has been associated with an increased risk of emergency admission to the hospital for patients with IBD (127,128). However, in a large study of Veterans Association patients, the association between NSAID use and IBD flares was believed to reflect residual bias rather than a true causal association. When evaluating patients with both NSAID use and IBD, there were similar rates of disease activity pre-exposure as postexposure (129). In a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies with a low risk of bias, NSAID use was associated with an increased risk of CD exacerbation (130). Selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in short-term therapy have not been shown to exacerbate UC, but similar studies have not been performed in CD (131).

Key concept

Cigarette smoking has been shown in multiple clinical situations to have an adverse effect on the natural history of CD. There is an increased rate of surgical intervention, incidence of IBD hospitalizations, and peripheral arthritis in patients with CD who smoke as compared with nonsmokers (132,133). Active smoking has been associated with a penetrating phenotype in CD and increased risk of relapse with anti-TNF discontinuation (134). However, patients with CD who stop smoking have fewer disease flares and decreased need for corticosteroids and immunomodulatory therapy (135). Because cigarette smoking is a potentially modifiable variable affecting the clinical course of CD, current smokers should be counseled regarding risks of ongoing cigarette use and provided with smoking cessation resources (136).

Key concept

Many patients associate psychosocial stressors with increased CD symptoms. There is a high prevalence of anxiety and depression among patients with IBD with up to one-third of patients reporting anxiety and a quarter of patients with depressive symptoms (137). These comorbidities are associated with increased health care utilization including emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and treatment escalations (138–140). The psychosocial stressors affect CD management, likelihood of disease control, and quality of life. Multiple studies demonstrate a strong relationship between depression and anxiety with IBD symptoms and with increased risks of disability (125,141–144). Screening for anxiety and depression is an important preventive care measure for patients with IBD alongside using available resources for psychosocial support (136).

MANAGEMENT OF DISEASE

General principles

Management recommendations for patients with CD are based on disease location, severity, presence of disease-associated complications including extraintestinal manifestations, and factors affecting future prognosis. The anatomic distribution of disease is important primarily for medications with targeted delivery systems, such as enteric-coated budesonide. For all other agents (i.e., systemic corticosteroids, thiopurines, methotrexate, biologics, and oral small molecules), therapeutic activity against CD is believed to occur throughout the entire GI tract.

Therapeutic approaches are individualized with the composite goal of achieving clinical and endoscopic remission without significant adverse effects of treatment (145). CD treatment should be considered as a sequential continuum to treat acute disease or induce clinical remission and then to maintain response/remission with overall improvements in quality of life.

Objective evaluation by endoscopic, sonographic, or cross-sectional imaging is recommended to confirm the subjective improvement of symptoms. In general, clinical evidence of improvement should be evident within 2–4 weeks, and the maximal improvement should occur by 12–16 weeks. Patients achieving response or remission are then transitioned to appropriate steroid-sparing maintenance therapy. Patients with continued symptoms after induction warrant assessment to determine whether medication optimization, addition of other agents or transition to a different treatment strategy, either medical or surgical, according to their clinical status, disease activity, extent, and behavior is warranted.

For patients with continued active symptoms despite optimized therapy, evaluation with an objective study such as IUS, cross-sectional imaging (CTE or MRE), or endoscopy (e.g., ileocolonoscopy) is recommended to determine whether active disease is still present. While biomarkers of disease activity can be assessed (e.g., CRP, FC), these should not exclusively serve as a treatment endpoint because normalization of the biomarker may occur in the presence of active mucosal inflammation/ulceration. In addition, mimickers of active IBD such as C. difficile infections, cytomegalovirus infection, and medication-related adverse effects should be excluded. Patients with IBD have a higher carriage rate of toxigenic C. difficile as compared with controls (146,147). In patients who have an increase in symptoms of diarrhea after antibiotic therapy, concurrent C. difficile infection should be considered and evaluated. The risks of C. difficile infection may be up to 5-fold higher among patients with IBD, particularly those with additional risk factors such as corticosteroid use, anti-TNF use, hospitalization, or other comorbidities (148).

Therapeutic drug monitoring has become very common in the management of CD (149), especially among patients who initially responded to anti-TNF therapy but then developed loss of clinical response (secondary loss of response), and this approach has been endorsed by several national and international groups (150–153). If active CD is documented for persons receiving anti-TNF therapies, then assessment of anti-TNF drug levels and antidrug antibodies (therapeutic drug monitoring) should be considered. There can be 3 different scenarios explaining biologic failure: mechanistic failure, immune-mediated drug failure, and finally non–immune-mediated drug failure. Individuals who have therapeutic drug levels and no antibodies with the presence of active mucosal ulceration are considered to have mechanistic failure and a medication within another class and mechanism of action should be considered (e.g., in a patient on anti-TNF therapy with active inflammation, consideration of anti-IL or anti-integrin therapy). Non–immune-mediated pharmacokinetic mechanisms occur when patients have subtherapeutic trough concentrations and absent antidrug antibodies. This scenario is a consequence of rapid drug clearance, classically in the setting of a high inflammatory burden. Immune-mediated drug failure is seen in patients who have low or undetectable trough concentrations and high titers of antidrug antibodies. Published guidance has suggested minimal therapeutic target trough levels; infliximab >5 μg/mL, adalimumab >7.5 μg/mL, and certolizumab pegol >20 μg/mL (151,153). Of note, patients with a history of anti-TNF antibodies are at a greater risk of developing antidrug antibodies to the next agent within the same class. Therefore, combination therapy with immunomodulators such as the thiopurines or methotrexate should be considered (154).

There is a suggestion that higher anti-TNF drug levels are associated with better rates of fistula healing (155–161). This association has been found in numerous trials; however, the quality of many of these studies have been limited as a consequence of their use of subjective outcomes and observational designs. There are, however, no high quality, interventional data available.

We note that this is partly because performing high quality clinical trials in perianal fistulizing CD can be challenging and costly. Moreover, conducting, and interpreting therapeutic drug monitoring studies impose their own challenges. Drug level concentrations may vary between laboratories and assays, which limits the extrapolation and comparison of results. Moreover, endpoints may vary across studies and patient demographics and selection may also complicate the interpretation of the data. Ultimately, further interventional, randomized controlled trials looking into the relationship between drug exposure and fistula outcomes are needed.

Working definitions of disease activity and prognosis

Disease activity reflects the combination of symptoms and endoscopic findings, whereas prognosis is the compilation of factors predictive of a benign or a more complicated course with greater likelihood of surgery and/or disease-related disability.

An individual may be in clinical, endoscopic, histologic, or surgical remission. Although most clinical trials have used the CDAI to assess therapeutic outcomes, a more clinical working definition for CD activity is of greater value for the practicing provider to guide therapy in an appropriate manner. Of note, the CDAI is a measurement meant primarily for clinical trial use, not clinical practice. For clinical practice, disease activity is assessed by a combination of clinical symptoms (e.g., abdominal pain, stool frequency) plus elevated inflammatory biomarkers or disease activity identified on radiologic or endoscopic assessments. Clinical remission, corresponding to a CDAI score 145). Endoscopic remission is described as the absence of ulceration with minimal mucosal abnormalities on ileocolonoscopy. Histologic remission refers to the absence of inflammatory cells, particularly neutrophils, on mucosal biopsy (145). Surgical remission indicates patients who are status post surgery such as ileocolonic resection and have no residual active disease during postoperative endoscopic assessment. Individuals who require the use of conventional corticosteroids to achieve clinical well-being are said to be steroid-dependent and are not considered to be in remission because of adverse events which accrue in patients with chronic use of systemic corticosteroids.

Individuals with mild disease are at lower risk of disease progression or future surgery and have no systemic signs of toxicity such as fevers, unintentional weight loss, or inability to tolerate oral intake. Objectively, biomarkers (CRP, calprotectin) may be normal to slightly elevated, and there is only limited anatomic involvement with scattered aphthous erosions or few superficial ulcers. These individuals do not have severe endoscopic lesions, strictures, fistulizing, or perianal disease (15,162,163).

Individuals are considered to have moderate–severe disease if they have not responded to treatment for mild–moderate disease or if they present with more prominent symptoms such as fever, significant weight loss, abdominal pain or tenderness, intermittent nausea or vomiting. Inflammation-related biomarkers (e.g., CRP, albumin, calprotectin) are more likely to be abnormal, and other factors such as anemia or vitamin/mineral deficiencies may also be present. These patients typically have greater endoscopic disease burden including larger or deeper ulcers, strictures, or extensive areas of disease and/or evidence of stricturing, penetrating, or perianal disease.

Individuals with severe/fulminant disease have persistent symptoms despite the introduction of conventional corticosteroids and/or advanced therapies or present with high fevers, evidence of intestinal obstruction, significant peritoneal signs such as involuntary guarding or rebound tenderness, cachexia, or evidence of an abscess usually requiring hospitalization. They also have endoscopic or radiographic evidence of severe mucosal disease.

There has been a move by regulators to require patient-reported outcomes for regulatory approval of new therapeutic agents for the treatment of patients with CD. The primary endpoint is to measure an endpoint that matters to patients. The European Medicines Agency is moving away from the use of the CDAI to focus on patient-reported outcomes such as stool frequency and abdominal pain and separately, objective measures of disease, such as findings on endoscopy (164). The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had done the same initially but is currently back to using the CDAI and objective measures of disease such as findings on endoscopy as primary clinical trial endpoints (165).

Mucosal healing

Key concept

Mucosal healing has become an important target goal when assessing efficacy of treatment for IBD (145). In patients with CD, mucosal healing has traditionally been defined as the absence of ulceration visualized during endoscopy (166,167). There are a limited number of studies that have examined the long-term impact of endoscopic healing on the clinical course of disease. In patients with early-stage CD, complete endoscopic healing after 2 years of therapy predicts sustained steroid-free, clinical remission 3 and 4 years out from initiation of treatment (168). Other clinical outcomes associated with mucosal healing in CD include decreased rates of surgery and hospitalizations (169–171). With histologic remission, typically defined as absence of neutrophils on biopsy in addition to endoscopic healing, there may be lower associated risks of clinical relapse, corticosteroid use, or treatment escalation (172).

There are several scoring systems that assess ulcer size, depth, and distribution throughout the ileum and colon including the SES-CD, the Crohn’s Disease Endoscopic Index of Severity, Simplified Endoscopic Mucosal Assessment for Crohn’s Disease (simplified endoscopic mucosal assessment for CD, based on the SES-CD), and the Rutgeerts score to evaluate the postoperative neoterminal ileum (Supplementary Information online) (79,173–175). Allez et al described the severe endoscopic lesion group as patients with large confluent and deep ulcers that occupy >10% of the surface area of at least 1 segment of the colon. These lesions, particularly in the ileum and rectum, may be more refractory to medical therapy (176–178). The SES-CD has been helpful to translate endoscopic activity into clinically meaningful findings that are easier for the clinician to understand. SES-CD scores may be categorized as 0–2 representing endoscopic remission; mild (3–6), moderate (7–15), and severe (>15) disease activity. Converting these findings into descriptive terms, mild endoscopic activity would consist of limited aphthous erosions involving less than 10% of the surface area and/or altered vascular pattern, erythema, and edema affecting less than 50% of the surface area. Moderate endoscopic activity would consist of erosions or superficial ulcers taking up >10% but less than 30% of the surface area and severe disease as large ulcers >2 cm (79,179).

The SES-CD scoring system has been used prospectively to assess mucosal healing in patients treated with advanced therapies (i.e., anti-TNFs, anti-integrins, anti-ILs, Janus kinase [JAK] inhibitors) demonstrating that changes over time can be measured. Furthermore, there is a strong correlation between improvement in SES-CD and clinical outcomes of response and remission (79,180–184). For patients who have undergone ileocolonic resection, assessment of the small intestine just proximal to the anastomosis, recommended within the first year after surgery, may identify postoperative endoscopic recurrence well before the clinical recurrence of CD (185).

MEDICAL THERAPY

General approaches

Recommendation

Medical treatment of CD is usually categorized into induction and maintenance therapy. Regimens are generally chosen according to the patient’s risk profile and disease severity with a goal to achieve clinical and biomarker response within 12 weeks of treatment initiation followed by durable steroid-free control of disease activity including both clinical and endoscopic remission. It is important to acknowledge, however, CD clinical trials have only recently incorporated objective outcomes such as endoscopic improvement as a coprimary outcome (165). Another therapeutic goal is to prevent disease complications, such as strictures and fistulae. While medical therapy may be successful in some patients with fistulizing disease, including perianal disease, there is less evidence for medication efficacy in stricturing CD given the known fibrotic component of chronic strictures. Medical therapy used to treat CD primarily include supportive care including dietary-based strategies, corticosteroids and advanced therapies including anti-TNF agents, anti-integrins, anti-ILs, and JAK inhibitors.

A recent open-label randomized controlled trial (PROFILE—Predicting Outcomes for Crohn’s Disease Using a Molecular Biomarker) evaluated 2 separate approaches to the management of newly diagnosed CD, early combined immunosuppression with infliximab plus immunomodulator or accelerated step-up therapy where conventional management with corticosteroids was followed by immunomodulator, then followed by infliximab use. The primary endpoint was sustained steroid-free and surgery-free remission at week 48. Those in the early combined group were significantly more likely to achieve steroid-free and surgery-free remission (79% vs 15%). This study demonstrates the benefit of early intervention with advanced therapy as compared to a serial approach first requiring the use of conventional therapy (186).

Mild-to-moderate CD

Recommendations

Key concept

When treating patients with CD, therapeutics are chosen based on the patient’s clinical presentation and prognosis, that is, the risk of progression of their disease (see “Natural History” section). Risk factors for progression include young age at the time of diagnosis, ileal disease location, serological response to specific microbial antigens, initial extensive bowel involvement, presence of perianal/severe rectal disease, deep ulcers, and penetrating or stricturing phenotype at diagnosis (14,15,187). There is also a subgroup of patients who rapidly progress to complicated disease behaviors with stricturing disease leading to possible bowel obstruction, internal penetrating fistulas, or both, which are associated with greater likelihood of needing CD-related surgery (15).

Treating the patient with disease on the milder spectrum presents a conundrum. On the one hand, agents proven to be effective in patients with moderate-to-severe disease, such as the biologic agents, are undoubtedly effective in mild disease as well, even if such patients were not explicitly studied in randomized controlled trials. On the other hand, the risk of adverse effects and high cost of such agents may not be justifiable in a low-risk population. Unfortunately, few agents studied in milder disease populations have proven to be effective. The desire to avoid overtreating disease and exposing the mild patient to unnecessary risk has led to the widespread utilization of largely ineffective agents whose use cannot be justified by clinical evidence. For example, 5-aminosalicylates (5-ASAs) remain widely prescribed for the treatment of CD, despite considerable evidence demonstrating their lack of efficacy.

Patients deemed to be at low risk for progression of disease may be monitored with supportive care strategies directed at symptom control, but they must be followed carefully for signs of disease worsening or progression. Because the primary goal of CD treatment is normalization or at least substantial improvement of objective indicators of mucosal inflammation, providers should recognize that inadequate disease treatment based on expectant observation and alleviation of symptoms, especially for higher-risk patients, may expedite disease progression and development of complications.

Key concept

5-Aminosalicylates.

5-ASAs are topical anti-inflammatory agents which exert their effects within the lumen of the intestine. Although their use in UC has been well-established, the effectiveness of 5-ASAs in CD has not been supported by the published evidence. Oral mesalamine was not more effective compared with placebo for induction of remission and achieving mucosal healing in patients with active CD (188–191). Sulfasalazine, 3–6 g daily in divided doses, may be a modestly effective therapy for treatment of symptoms of patients with mild colonic CD and/or ileocolonic CD, but not isolated small bowel disease. However, sulfasalazine was not more effective than placebo for achieving mucosal healing in patients with CD even when used in combination with corticosteroids to induce then maintain remission. While 5-ASA suppositories or enemas are effective for induction and maintenance of remission for patients with mild to moderate UC; the role of topical mesalamine in CD, although commonly used, is of limited benefit (188,192–194).

5-ASAs have also been extensively studied for maintenance of medically induced remission of CD with equivocal benefit. There were 11 placebo-controlled trials of 5-ASAs, with doses ranging between 1 and 4 g per day and maintenance treatment duration between 4 and 36 months. Four of the studies reported a significant decrease in CD relapse compared with placebo; however, the other 7 studies showed no prevention of relapse (195–205). There were 5 meta-analyses evaluating the efficacy of mesalamine for the maintenance of medically induced remission in patients with CD. The therapeutic advantage between mesalamine and control was 206–209). Given the totality of data, 5-ASAs are not recommended for maintenance of medically induced remission of CD.

Budesonide.

Corticosteroids are primarily used to reduce the signs and symptoms of active luminal CD and to potentially induce clinical remission; however, corticosteroids have not been consistently effective in achieving mucosal healing for patients. Ileal-release steroid formulations may be used for mild to moderate disease, whereas systemic corticosteroids are used for moderate to severe disease. They have historically been used as a bridge to permit symptom control until immunomodulators and/or biologic agents become effective and enable mucosal healing.

Although not as effective as conventional oral corticosteroids such as prednisone, controlled-ileal release (CIR) budesonide may be effective for short-term relief of symptomatic mild-to-moderate CD in patients with disease confined to the terminal ileum and right colon (210). CIR budesonide is a pH-dependent ileal release oral corticosteroid formulation with high topical activity and low systemic bioavailability (∼10%–20%). CIR budesonide has been demonstrated to be effective in randomized placebo-controlled trials for induction of remission in active mild-to-moderate ileocecal CD (210–212). The lesser efficacy of CIR budesonide is balanced against the agent’s release profile, limited to the ileum and right colon, and its topical activity with extensive first-pass hepatic metabolism, minimizing systemic exposure to corticosteroid effects.

Budesonide should not be used to maintain remission in mild to moderate CD. There were 6 randomized placebo-controlled studies evaluating maintenance of remission with budesonide. The 12-month relapse rates for 3–6 mg budesonide daily ranged from 40% to 74% and were not significantly different than placebo (213–217). Four meta-analyses have been published on the efficacy of budesonide dosed at 3–6 mg daily for maintenance of remission in CD. The results are mixed with most showing no benefit in maintenance of remission or in achieving mucosal healing, with only a slight improvement in mean time to symptom relapse but increased adverse events compared with placebo (218–221). In a Cochrane Database review of 12 studies (total 1,273 patients) which included 8 studies that compared budesonide with placebo, 1 study comparing budesonide with 5-ASAs, 1 compared with corticosteroids, 1 compared with azathioprine, and 1 comparing 2 doses of budesonide, budesonide was not effective for maintenance of remission beyond 3 months after induction. Although budesonide did seem to have some benefit in symptom response and a longer time for disease relapse, the risks for treatment-related adverse events including higher rates for adrenocorticoid suppression was observed (222). Therefore, whether disease activity recurs after a course of budesonide or whether there is an incomplete response to budesonide, additional evaluation is necessary to determine whether an advanced therapy is warranted vs whether other diagnoses are present that may be contributing to symptom presentation.

Key concept

Antimicrobial therapy.

In patients with CD, it is hypothesized that the development of chronic intestinal inflammation is caused by an abnormal immune response to normal flora in genetically susceptible hosts. The involvement of bacteria in CD inflammation has provided the rationale for including antibiotics in the therapeutic armamentarium. The precise mechanisms whereby broad-spectrum antibiotics are beneficial in the treatment of a subset of patients with CD are uncertain. Several proposed mechanisms of efficacy include direct immunosuppression (e.g., metronidazole), elimination of bacterial overgrowth, and abolition of a bacterially mediated antigenic trigger.

Although widely used in the past, the primary role of antibiotics for the treatment of luminal CD has not been supported by the evidence (223,224). Metronidazole is not more effective than placebo at inducing remission in patients with CD (225,226). Ciprofloxacin has shown similar efficacy to mesalamine in active CD but has not been shown to be more effective than placebo to induce remission in luminal CD. Neither of these agents has been shown to heal the mucosa in patients with active luminal CD (226–229). Rifaximin, a nonabsorbable predominantly luminally active antibiotic, has been studied for the induction of remission with a potential efficacy signal at higher than conventional dosing. However, the cumulative evidence has yielded inconsistent results, and maintenance of remission data is lacking (230,231).

Antibiotics may be used an adjunctive treatment for patients with CD with complications of CD. For example, for patients with perianal CD, the addition of antibiotics in combination with biologics or thiopurines to improve outcomes such as fistula closure may be considered (232,233). Antibiotics such as the nitroimidazoles may also have a role for postoperative prophylaxis for patients with low risk of CD recurrence postresection (234). Broad-spectrum antibiotics are used for the treatment of pyogenic complications (e.g., intra-abdominal, mesenteric, or perianal abscesses) in patients with CD.

The relationship of mycobacterial disease, specifically Mycobacterium avium paratuberculosis (MAP), to the development of CD has been extensively evaluated. The absence of MAP in all tissue examined (even when assessed by PCR) and the lack of significant patient disease benefit when treated with multidrug regimens has led to the recommendation that anti-MAP therapy should not be used to treat patients with active CD. Anti-MAP therapy has not been shown to be effective for induction or maintenance of remission or mucosal healing in patients with CD (235,236).

Key concept

Diet.

Some studies suggest that dietary therapies, including elemental, semielemental, and defined diets, may be effective for select patients with CD to reduce clinical symptoms and disease activity scores. When discussing dietary-based strategies as primary treatment, the CD patient’s current disease activity and risks for disease progression and complications need to be considered. Most of the diet-based studies were performed primarily among pediatric patients with CD. In the adult patient population, these benefits are often not durable with symptoms and active inflammation reoccurring on resumption of an unrestricted diet (237,238). The CD exclusion diet has been developed to reduce exposure to potential proinflammatory elements and has been shown in several studies to induce remission primarily among patients with mild to moderate CD (237,239,240). The DINE-CD study, a randomized trial comparing the specific carbohydrate diet to the Mediterranean diet for adult patients with CD, revealed no differences in symptomatic remission and biomarker response between the 2 diet-based strategies for patients with mild-to-moderate CD (241). Adherence to a Mediterranean diet for at least 6 months was associated with improvement in biomarkers and quality of life among patients with CD (242), Therefore, a primary dietary-based treatment approach should be limited to patients with limited disease and low risks of disease progression. Routine monitoring with symptom, laboratory, and diagnostic assessments remains important to identify disease progression (243).

Moderate-to-severe CD

Corticosteroids recommendations

Patients experiencing moderate-to-severe symptoms or who have multiple high-risk features for disease progression and complications require treatment with advanced therapy. Conventional corticosteroid treatment, such as prednisone and methylprednisolone given orally or intravenously for more severe disease, is effective in alleviating signs and symptoms of a flare (244). The appropriate prednisone equivalent doses used to treat patients with active CD range from 40 to 60 mg/d (245,246). These doses are typically maintained for 1–2 weeks and tapered at 5 mg weekly until 20 mg and then 2.5–5.0 mg weekly. Corticosteroid tapers should generally not exceed 3 months. Oral prednisone doses or equivalent doses in other oral steroids exceeding 60 mg a day are not recommended. There have been no adequately powered comparative trials between different steroid-tapering regimens in the treatment of patients with CD.

The use of corticosteroids should not exceed 3 continuous months without attempting to introduce corticosteroid-sparing agents (such as biologic therapy or immunomodulators). Even short-term use may be accompanied by important adverse events, such as severe infections, accelerated bone loss, elevated blood glucose, glaucoma, weight gain, venous thromboembolic events (5-fold increased risk), and cardiovascular disease (38,244,247,248).

Despite their effectiveness in reducing signs and symptoms of active CD, nearly 1 in 4 patients will have prolonged exposure to corticosteroids (i.e., greater than 6 months), particularly earlier in their disease course with approximately 15% of patients becoming steroid-dependent with an inability to taper without subsequent recrudescence of symptoms (249). In a meta-analysis including 403 patients with surgically or medically induced remission, corticosteroids were not effective at maintaining remission (250). The rates of remission were no different between placebo and corticosteroids at 6, 12, and 24 months. Prolonged or recurrent corticosteroid use may decrease the effectiveness of steroid-sparing agents for mucosal healing, even among those who experience symptomatic relief. In addition, corticosteroids are implicated in the development of perforating complications (abscess and fistula) and are relatively contraindicated in those patients with such manifestations. For all these reasons, corticosteroids should be used sparingly in CD. Once started, care should be taken to ensure that corticosteroids are successfully discontinued with a gradual taper and steroid-sparing agents added.

Immunomodulators recommendations

Key concept

Because of their relatively slow onset of action of 8–12 weeks, thiopurines are not effective agents for induction of remission among patients with active, symptomatic disease (251,252). There are 3 scenarios by which a thiopurine is used after corticosteroid induction of remission. One scenario is to initiate the thiopurine at the time of the first course of corticosteroid, the second is after repeated courses of corticosteroids or in patients who are corticosteroid-dependent (i.e., unable to taper the steroid without CD relapse), and the third is as a concomitant medication with an anti-TNF agent to reduce the risk of development of antibodies and improve pharmacokinetic parameters. For patients with moderate-to-severe CD who remain symptomatic despite current or prior corticosteroid therapy, the thiopurine analogs azathioprine (at maximal doses of 1.5–2.5 mg/kg/d) or 6-mercaptopurine (at maximal doses of 1–1.5 mg/kg day) may be used as a steroid-sparing maintenance agent. TPMT testing should be checked before initial use of azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine to identify patients at increased risk for thiopurine-associated myelosuppression (253,254). Variants in the NUDT15 gene have also been demonstrated to affect thiopurine metabolism leading to increased medication related toxicity among particularly among people of East-Asian, Latino, and Native American ancestries. Testing for NUDT15 genetic variants should be considered if available (255–257).

For newly diagnosed pediatric CD, 6-mercaptopurine, dosed at 1.5 mg/kg/d, administered in combination with the first course of corticosteroids, has demonstrated efficacy (258). Presumably, the same efficacy would be realized with azathioprine in an adult population, but a randomized open-label study of early use of azathioprine in CD was unable to demonstrate a benefit with respect to time in clinical remission (259).

Adverse effects of azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine include allergic reactions, pancreatitis, myelosuppression, nausea, infections, hepatotoxicity, nonmelanoma skin cancer, and lymphoproliferative disorders (260,261). The risks of skin cancer and lymphoma have been demonstrated in multiple observational studies with increasing risks attributed to ongoing use of thiopurines, duration of exposure, and increasing age. While, reassuringly, these risks seems to decrease with medication discontinuation, the aggregate risks of adverse effects with longer-term use of these agents needs to be factored along with the efficacy data from earlier clinical trials and the availability of other CD options to treat moderate-to-severe disease (262–265). Although these agents may be considered as steroid-sparing maintenance agents, accumulating risks associated with thiopurine exposures may outweigh the original steroid-sparing benefit particularly with the other mechanisms of action now available, which have a more favorable safety profile.

Methotrexate is also effective as a corticosteroid-sparing agent for the maintenance of CD remission (266–268). Parenterally (subcutaneous or intramuscular) administered methotrexate at doses of 25 mg per week is effective for maintenance of remission in CD after steroid induction (268,269). If steroid-free remission is maintained with parenteral methotrexate at 25 mg per week for 4 months, the dose of methotrexate may be lowered to 15 mg per week (270). Patients with normal small bowel absorption may be started on or switched from parenteral to oral methotrexate at 15–25 mg once per week; however, controlled data with oral methotrexate as a primary treatment for CD are lacking. For patients with extensive small bowel disease or risk factors for malabsorption, the bioavailability of oral methotrexate at higher dosages may be variable. Thus, parenteral methotrexate may be the preferred route of administration in this context (271).

Adverse effects related to methotrexate include nausea and vomiting, hepatotoxicity, pulmonary toxicity, bone marrow suppression and skin cancer, and likely lymphoma; however, an escalated risk of lymphoma has not been conclusively demonstrated in patients with CD. The white blood cell counts and liver chemistries should be routinely monitored during their use. When prescribed to women with child-bearing capability, methotrexate should be administered only if highly effective contraception is in place (272,273).

Thiopurines or methotrexate may also be used as adjunctive therapy for reducing immunogenicity for patients on anti-TNF therapy (6-mercaptupurine or azathioprine typically at reduced doses and methotrexate 12.5–15 mg orally once weekly) (65,274,275). Antidrug antibodies associated with anti-TNF therapies, particularly infliximab and adalimumab, can develop as early as the first 100 days of treatment, particularly with anti-TNF monotherapy. Factors such as active smoking status, increased body mass index, and anti-TNF monotherapy may be associated with lower drug levels at week 14 and greater risks of loss of response, whereas earlier initiation of combination therapy with immunomodulators may yield more durable effectiveness (65,276).

Anti-TNF agents recommendations

The anti-TNF-α therapies approved for moderate to severe CD include infliximab, a chimeric mouse-human IgG1 monoclonal antibody available as intravenous infusions and subcutaneous injections; adalimumab, a subcutaneous fully humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody; and certolizumab pegol, a subcutaneous pegylated Fab fragment to TNF-α. These biologic agents are effective for treating patients with CD with objective evidence of active disease and inadequate response to corticosteroids, thiopurines, and/or methotrexate, especially patients with multiple risk factors for disease progression (i.e., younger age at diagnosis, ileal disease location, extensive disease, larger/deep ulcers on endoscopy). The anti-TNF agents have a potentially rapid onset of action occurring as early as within the first 2 weeks of treatment initiation (277). However, treatment with anti-TNF agents also seems to be more effective when given earlier in the course of disease because rates of response and remission are higher if given within 2 years of onset of disease. In the PROFILE study, top-down treatment with combination infliximab plus immunomodulator achieved substantially better outcomes at 1 year than accelerated step-up treatment. The use of biomarkers did not show clinical utility. Therefore, top-down treatment should be considered the standard of care for patients with newly diagnosed active CD (186).

Infliximab, adalimumab, and certolizumab pegol are also effective for maintenance of medically induced remission in luminal CD, and numerous clinical trials have supported the use of anti-TNF agents beyond induction (278–284). In a meta-analysis including 14 clinical trials (total of 3,995 patients), infliximab, adalimumab, and certolizumab were effective for maintenance of remission at weeks 20–30 among patients with CD who responded to induction therapy (285). In another meta-analysis of 5 trials (total of 1,390 patients), the RR of relapse at weeks 26–56 among patients treated with an anti-TNF agent compared with placebo was 0.71 (95% CI 0.65–0.76). The number needed to treat with an anti-TNF agent to prevent 1 patient with CD to relapse after remission of active disease achieved was 4 (95% CI 3–5) (286). In a Cochrane Database review, the pooled analysis of 5 or 10 mg/kg infliximab every 8 weeks was found to be superior to placebo for maintenance of remission and clinical response at week 54; 400 mg certolizumab pegol every 4 weeks was superior to placebo for maintenance of remission and clinical response at week 26, and 40 mg adalimumab every other week or every week was superior to placebo for maintenance of clinical remission at week 54 (287).

Infliximab is the only anti-TNF agent available as either an intravenous or subcutaneous maintenance therapy for patients with CD. The initial phase 1 study highlighted the pharmacokinetic noninferiority of subcutaneous vs intravenous infliximab in terms of efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity (288). In the phase 3 randomized controlled trial, the LIBERTY trial, comparing maintenance dosing of subcutaneous infliximab with placebo after standard infliximab induction, 62% of subcutaneous infliximab-treated patients achieved clinical remission at week 54 compared with 32% of placebo patients. Over 50% of subcutaneous infliximab patients had endoscopic response compared with only 18% of placebo-treated patients (289). Subsequently, additional studies of subcutaneous infliximab yielded similar findings, highlighting the effectiveness and safety of this agent as another option for patients where infliximab maintenance is recommended (290). However, some patients transitioning to subcutaneous infliximab 120 mg every other week may require dose escalation to 240 mg subcutaneous every other week to achieve or recapture response. The REMSWITCH study was a multicenter observational study which evaluated patients in steroid-free clinical remission on variable but stable dosing of infliximab (5 or 10 mg/kg every 4, 6, or 8 weeks) transitioning to subcutaneous infliximab 120 mg every 2 weeks. Disease relapse was more likely to occur among patients taking higher or more frequent dosing of infliximab by weeks 16–24 postswitch: 10.2% (5 mg/kg every 8 weeks), 7.3% (10 mg/kg every 8 weeks), 16.7% (10 mg/kg every 6 weeks), and 66.7% (10 mg/kg every 4 weeks). Importantly, dose escalation to 240 mg every other week led to recapture clinical remission in 93.3% and clinical + biomarker remission (based on FC) in 80% of patients. Patients who were receiving infliximab 10 mg/kg every 4 weeks and had an FC >250 μg/g were more likely to experience a flare, suggesting these patients may need a dose of infliximab 240 mg subcutaneous every 2 weeks at initiation (291).

Combination therapy with an anti-TNF agent and an immunomodulator has been demonstrated to improve short-term efficacy compared with monotherapy (292–294). Patients with CD treated with infliximab plus azathioprine or infliximab monotherapy were more likely to achieve corticosteroid-free clinical remission than patients receiving monotherapy azathioprine and with no notable differences in safety in the SONIC trial (292). The addition of a thiopurine or methotrexate with anti-TNF therapy may also improve pharmacokinetic parameters and reduce immunogenicity (293,294). In a recent genomic subanalysis of a prospective observational study of patients with CD starting adalimumab or infliximab, carriers of HLA-DQA1*05 were at an increased risk for development of antibodies against infliximab and adalimumab (65). However, earlier initiation of combination therapy may protective against immunogenicity allowing for greater persistence of treatment (276). Therefore, combination therapy may be the preferred strategy of treatment for patients with higher-risk CD who do not have risk factors precluding its use.

A 2023 meta-analysis of 13 studies found that HLA-DQA1*05 variants are associated with a higher risk of immunogenicity and secondary loss of response in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases treated with TNF-α antagonists. The risk of immunogenicity in those patients with HLA-DQA1*05 variants was 75% higher than noncarriers, and the risk of secondary loss of response was 123% higher than noncarriers with a positive predictive power of 30% and a negative predictive power of 80%. The meta-analysis also found that proactive therapeutic drug monitoring can modify the association between HLA-DQA1*05 variants and immunogenicity (295).

The benefits and risks of combination therapy must be individualized. There is a higher risk of lymphoma in patients treated with azathioprine or 6 mercaptopurine, especially among older patients and with longer duration of exposure (251). There is also a rare but increased risk of hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma particularly for younger males treated with combination anti-TNF and thiopurine therapy (296). For patients where combination therapy is considered higher risk, optimized infliximab monotherapy with targeted therapeutic drug monitoring may be considered, avoiding long-term use of thiopurines and potential associated toxicities (297,298). Some evidence suggests that immunogenicity may be prevented with proactive therapeutic drug monitoring and maintaining robust trough levels of the TNF antagonist while on infliximab monotherapy because the primary effect of immunomodulator in combination therapy is in nonspecifically increasing drug trough concentrations (299). In a post hoc analysis, among patients with CD with similar infliximab serum concentrations, combination therapy with azathioprine was not more effective than infliximab monotherapy (300). However, a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing proactive therapeutic drug monitoring to conventional approaches did not identify a clinical benefit for anti-TNF treated patients (301).

The safety profile of anti-TNF agents is generally favorable, but a small percentage of patients may experience severe side effects. A meta-analysis of 21 anti-TNF clinical trials including 5,356 patients with CD concluded that anti-TNF therapy did not increase the risk of serious infection, malignancy, or death compared with placebo (285). However, clinical trials of 1 year duration may not be sufficiently large or long enough to detect adverse events. In addition, these agents are safe to use during preconception planning, throughout pregnancy and postpartum (302,303). Individuals at increased risk for use of anti-TNF therapy include patients with prior demyelinating disorders (e.g., optic neuritis and multiple sclerosis), congestive heart failure, and individuals with a history of lymphoma or malignancies. Infectious complications may occur with the use of these agents, and thus, vigilance is advocated when treating these patients including routine laboratory monitoring, counseling regarding potential adverse effects, and recommended pretreatment assessments (304).

Before anti-TNF therapy is considered for use in patients with CD, pretreatment screening for infections and laboratory abnormalities is required. Testing for latent and active tuberculosis should be undertaken as well as assessment of patient risk factors for exposure. Interferon-γ release assays are likely to complement the tuberculin skin test and are preferred in patients who are Bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccinated, if available. Similar testing and therapy should also be considered before corticosteroids or other immunomodulators in patients at high risk of tuberculosis. If latent tuberculosis is detected, initiation of chemoprophylaxis with antituberculous therapy should be initiated for several weeks before administration of anti-TNF therapy. It may be appropriate to consider a second tuberculin skin test in an immunocompromised host after the initial test is negative. This is classically done 1–3 weeks later (305).