Human beings have a tendency toward collection. I have a theory that this desire to hang onto things is more true in times of crisis, but lately, I’ve begun to believe that we also have a tendency toward crisis itself. This makes untying the impulse to collect and the challenges of the times a fairly impossible task. In her new book, Black in Blues: How a Color Tells the Story of My People (2024), scholar Imani Perry sets up the intertwined story of two shifting and impossible collections: the color blue, and the nature of Blackness. For Perry, blue is at the core of a fundamental understanding of human stories: In her words, “There was a time before Black, but not before blues.”

Blue projects have captivated writers throughout time. A few notable examples: Maggie Nelson’s 2009 Bluets, William H. Gass’s 1975 On Being Blue: A Philosophical Inquiry, and Toni Morrison’s 1970 novel The Bluest Eye. Fred Moten wrote a contemplation on blue and black for the Pulitzer Art Foundation’s 2017 exhibition Blue Black, curated by Glenn Ligon, who also offered meditations on the colors and their associations. (The exhibition drew its title from Ellsworth Kelly’s monumental work of the same name, which hangs in perpetuity in the Pulitzer’s Tadao Ando building in St. Louis.) Musicians like Duke Ellington and Nina Simone play the blues. Picasso went through a blue period.

I went through my own blue period as an artist in 2016 and 2017, during which I both suffered from an uneasy case of politically motivated agoraphobia and collected over 190 images of different shades of blue, captured by photographing uninterrupted squares of sky on cloudless days. This project, which I titled #sky #nofilter, wound up progressing far beyond the photographic. It eventually appeared in such varied forms as a silent work of video art that shifts through my blues for a little over 34 minutes; a performance lecture about the nature of enduring during uncertain political times that was later published as a chapbook; a series of studies exploring different ways to translate digital blues into physical materials; and the project’s final version: a public sculpture in the form of an analemmatic sundial, commissioned by and permanently installed at the California African American Museum in Los Angeles. The sundial uses the human body as the gnomon, or the shadow-casting object by which time is told, requiring two participants for a complete reading: one to stand and mark the shadow, and the other to read the text of the panel on which the shadow hovers closest. The sundial as a marker of time was my attempt to harness color and emotion, two fleeting realities.

For Perry, as for me, the process of collecting blues is a step toward assembling memory. This collecting impulse allows us to move beyond interlinked crises in the past and present, providing us with the materials we need to build a different future. “One of the remedies we who study Black life have pursued is diligent recovery in the face of being forgotten, obscured, or submerged. We piece together clues and uncover hidden stories,” she writes in one of the book’s interconnected vignettes. “This work is important because the work of remembering is also the work of asserting value to what and who is remembered. It matters to know [Thomas] Commeraw’s name and cherish his work. And yet it also matters to remember his personal adversity, even in a life of achievement. And all the shattered stories and names that will never be recovered.”

I appreciate the acknowledgment of complexity within her statement: that the construction of memory is also imbued with at least some awareness of all that has been forgotten. Commeraw, a once-enslaved Black ceramicist known for making stoneware, is remembered through his lingering objects, but not necessarily for the particulars of his life. In my own project, the phrase “forgetting is essential to survival” appears both on a panel of the sundial and within the chapbook, anchoring a work that was fundamentally about the collection of two of the most ephemeral things of all: the color of the sky in a specific moment of a specific day, and emotions. Frail and meaningful items bound to time and subject to interpretation, often past before we’ve even caught them. Perry’s recollections throughout Black in Blues consistently allow for more complex realities. At each phase, there is an essential split that occurs: two poles between the remembered and the forgotten. Two more between the forgotten-by-accident and the forgotten-on-purpose. Two more still between purposeful forgetting as protection, and purposeful forgetting as violence. In these increasingly smaller breakdowns, the categories of black and blue are ever less monolithic and yet more interconnected.

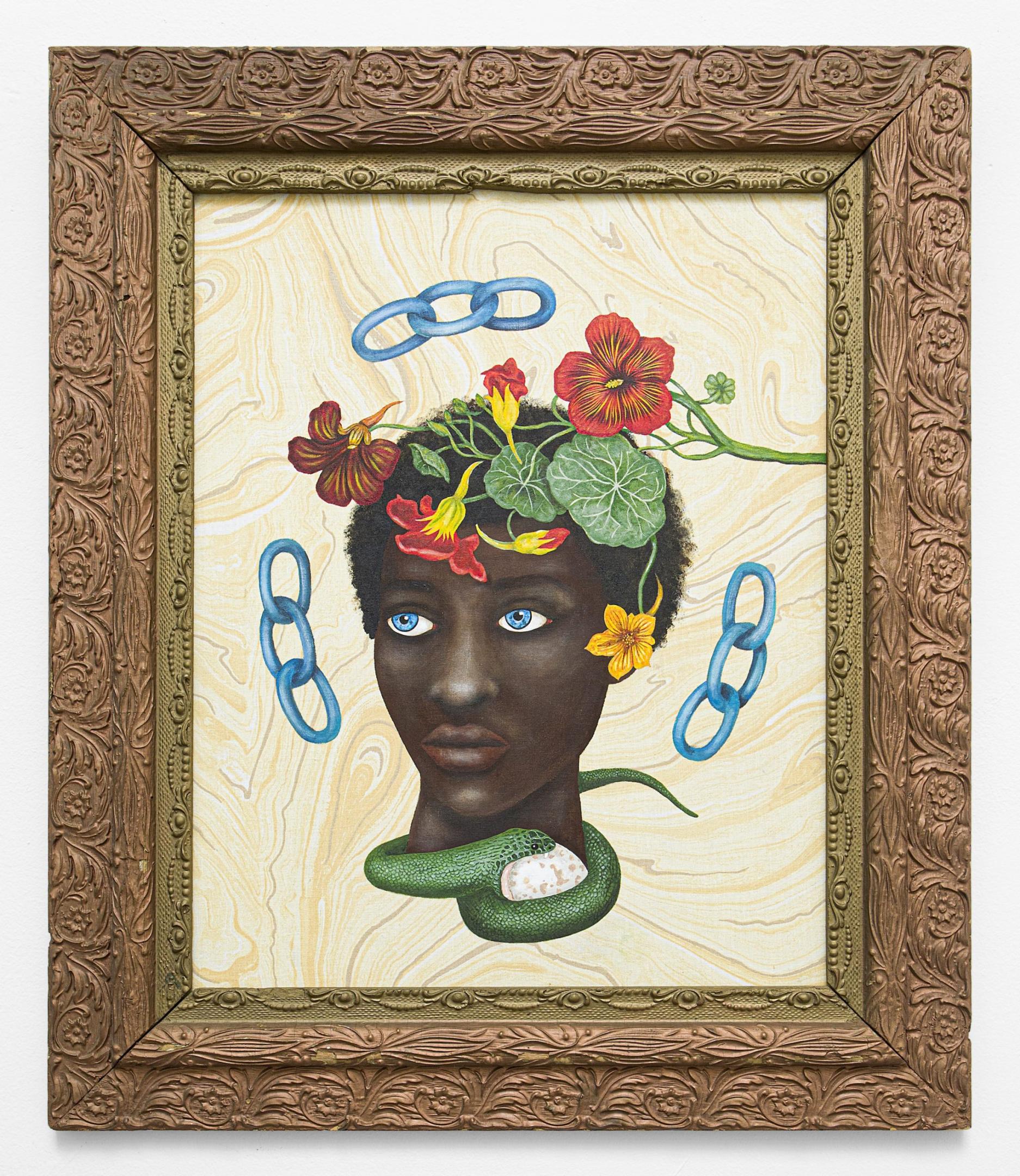

My favorite moments of Black in Blues come when Perry illuminates certain truths about value. In the field of color, the term “value” refers to relative lightness or darkness, the position of the color between “pure white” and “pure black.” For a visual artist, the understanding and reproduction of value is in one sense a way to denote depth. Perry upends this metaphor of value, leaving us with stories of blue as connected to the violence of ownership: the sale of blue in Yoruba marketplaces transformed when the sellers of blue can become, themselves, sold. Elsewhere, she details how the color blue passes from rarity (indigo, lapis lazuli) to common use based on practical necessity (denim production during the days of slavery in the United States and Union army uniforms repurposed as police uniforms during the Reconstruction period). She returns to poles: blue-eyed to blue-black. The height of the sky and the depth of the ocean. Triumph and tragedy. Blue as both possibility and limitation.

An extensively well-researched volume, some portions of the text feel speculative, with respect to both style and economics. For swaths of history that cannot be known — in part due to their deliberate erasure — Perry uses acts of speculative fiction to weave a narrative that empathetically connects us to the experiences of Black people whose futures were, as they to various extents continue to be, traded for White economic speculation. Journeying from the Nigerian marketplace to the American slave market, Perry introduces a series of questions and descriptions that put us in the mindset of an indigo-dyed textile trader now in the process of being sold, the shocking transformation from seller to object. Undoing or complicating an idea of ownership, Perry uses this description as a way of commanding history. But the nature of writing, unlike other forms of usage (commerce, consumption, and so on), is that it offers a control that does not diminish the resource being described. Perry writes to harness a complex story of shifting blues, offering us an open-ended gift.

Black in Blues is not a journey with a resolution. The condition of Blackness — or of anything off-color to normativity — has become increasingly fraught over the past few days of DEI-backtracking, the feared cancellation of Black History Month (or any “diversity month”), and ongoing interlinked threats to both public health and the climate crisis. Yet we must persist. Toward the end of the book, Perry writes, “I think — and I’m not sure this is true, but it seems right to me — that the most important preservation is not perhaps a particular place or thing, but a sensibility that lies in blues, that of living as a protest. It can remain even when recordings degrade and buildings crumble. Spiritual sustainability is a natural condition for those on the underside of empire.”

The state shifts. Language changes meaning based on usage or out of necessity. The sky recolors itself through sunrise, weather, ash, or dusk. The work, both to chronicle and to repair, continues.

Black in Blues: How a Color Tells the Story of My People (2024) by Imani Perry is published by Ecco and is available online and through independent booksellers.