|

| Can Art Save the High Street? |

Remember those bustling

Saturdays on the high street, the shared joy of finding a bargain, or the

anticipation of trying on a new outfit? Those bygone moments seem increasingly

distant, replaced by boarded-up shops and the convenience of online clicks. But

is the decline of the high street inevitable and can art and creativity really save

it?

This time I explore a

different path for high streets around the world – one where art becomes the

vibrant paintbrush, reimagining the high street as a canvas for community,

experience, and possibility.

This post marks a milestone –

my 400th blog! With artificial intelligence (AI) on the rise and people busier

than ever, I wondered about the future of blogs and the direction I should take

with this site. Some might see blogs as outdated, but AI can’t replicate humanity

without it appearing fake or stereotyped – nor can it convey the

“why” behind my art.

Blogs remain a powerful way to

connect with a real audience and a way for artists to provide the narrative to

their work and the thinking behind it. That’s something that is difficult to

convey through a regular artist website, most are geared towards driving

traffic to purchase routes and I think art, and artists deserve more than that,

but maybe I’m just old school.

So, I’m embracing my humanity

and focusing on what AI can’t do. I’ll be diving deeper into my retro-inspired

work, providing a narrative alongside the art that documents the what, when,

and why, rather than the previous 399 posts that have really focussed on sharing

knowledge and experience.

The art world constantly changes

but it also stays the same, once you gain experience it becomes easier to

navigate and by easy, I mean well, it will still be character building but

experience will give you the skills to get you through. I’ll still share

knowledge but it won’t be the sole focus of this site, there are 399 posts that

say what needs to be said that I’ve written already!

|

| Maggie’s Irish Pub by Mark Taylor |

Over the years, I’ve created

hundreds of pieces depicting life in the 70s, 80s, and 90s. While I’ve built a

collector base with landscapes and abstracts I haven’t shared much about these

“retro” works, which were often commissioned. I’ve painted icons and

memories from the 80s since the 1980s, everything from early digital pre-Warhol

period work right the way through to cover art.

From now on, expect a deeper

dive into my process behind the art. Ultimately, I want to create a visual

record of these three influential decades, a time of not just technological

revolution, but also a period in time that witnessed a major shift in people’s

attitudes towards everything from art to consumerism, even politics. I’m also

getting to that particular point in my art career that making a stand or making

a point with my work is an itch I need to scratch.

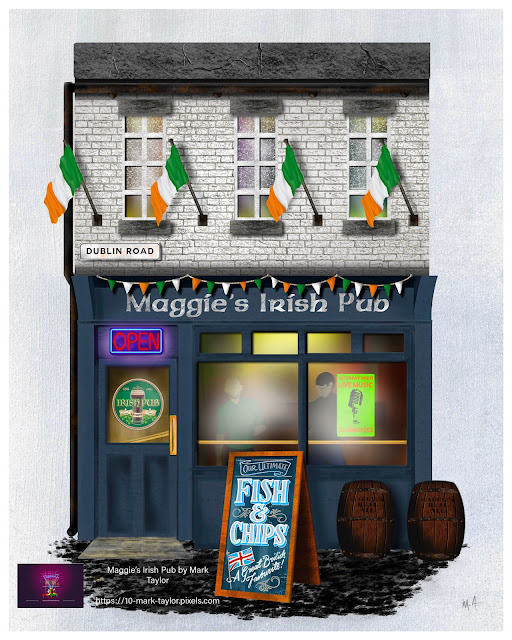

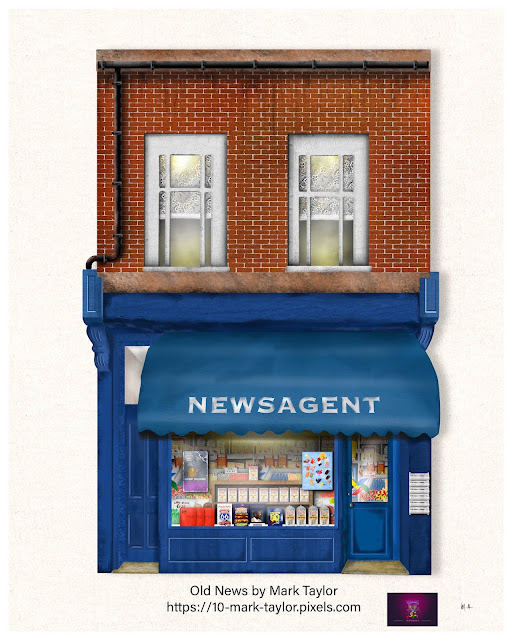

This post introduces my latest

series, exploring the changing face of the high street. Throughout this series I

juxtapose thriving businesses with those that have closed, reflecting the

decline of these once-sacred spaces.

It’s a reminder of what we’ve

lost and a look at the complex factors at play. The future of brick-and-mortar

stores is uncertain, with online giants like Amazon changing how we shop. We

might even question if the high street’s heyday was already fading in the 80s!

This series is a starting

point for a conversation – what will become of the high street?

The British high street, once

a bustling centre of life and commerce, now stands at a crossroads. This story

echoes across the globe: what were once proud symbols of community and commerce

are now boarded up, or filled with replacements that don’t quite capture the

same spirit.

In the UK especially, these

replacements can be puzzling. Small towns with ageing populations might have

seven Turkish barber shops, charity shops (thrift stores in the US), American

candy stores, and nail salons. Who needs that many barbers when there’s less

hair than customers?

Of course, this decline isn’t

universal. Thriving high streets still exist in some parts of Europe and the

US. But wherever decay sets in, for social, economic, or political reasons, a

shadow falls over the community.

Here in the UK, the

independent art supply store I relied on is gone. Now, a quick canvas for a

commission requires online ordering or a long drive. This has a ripple effect –

the high street used to be vital for local businesses to connect with each other.

Now, it’s a waiting game of unreliable deliveries, a system that doesn’t care

if your art supplies arrive broken.

Look, I know I might sound

like someone yelling at clouds, but I truly wish we could find something that

brings communities together again.

The exact start of the high

streets decline is hard to pinpoint. Some high streets thrived longer than

others. But for Britain, I suspect the 1980s marked a turning point. The decay

crept in slowly, cracks appeared that we just didn’t see at the time.

|

| A High Street Heartbeat Fades by Mark Taylor |

Out of town shopping centres,

although popular in the early to mid-1970s, began to sprawl into new urban

areas. In the United Kingdom, new towns had been created to manage the

population overspill from surrounding areas, old minefields were converted into

housing estates, development corporations sprang up, and Milton Keynes, a new

town way north of London had concrete cows installed in a field and everyone

thought it was fun.

Despite being newly created

with new people everywhere there was still a sense of old-small town community

present, but this spirit hinged on having lots of new town benefits such as

vibrant high streets, enough local facilities and police that policed, doctors

that doctored, and schools that didn’t have to compete for students through a

league table and that weren’t falling down because they used the wrong type of

concrete. I kid you not, that’s what’s happening with schools here in Blighty.

New homes were built at pace,

something that rarely happens in the modern day. High streets flourished from

new footfall and they really did become hubs for the community to gather. Out

of town shopping centres and malls were rapidly created, they offered a

convenience and had everything in one place and they had exciting and exotic

brands that could never be found in regular stores.

Malls, at least initially were

never seen as an immediate threat to the high street. They were still bricks

and mortar, and it was unlikely that small independent retailers would want to

go head to toe with the big players and they often sold very different things.

There was space for both.

The supermarkets and grocery

stores were some of the first to transition completely to the out of town malls,

they could carry much more stock and provide even more choice for customers in

the bigger locations. I remember a couple of supermarkets moving out of town,

but there were still smaller retailers who could fill the void, not everyone

wanted to visit the mall and not everyone could travel easily but when the

supermarkets began to leave the high street it would be another chip in the

fabric.

These out of town centres were

convenient but there was a reliance on either using public transport or

travelling by car, the traditional local high street still served a purpose

especially as car ownership in the UK during the 70s was still relatively low. So

why do I say the 1980s had been pivotal in the decline of high streets at a

time when high streets were still vibrant and booming?

Whenever I ask anyone this

question they undoubtedly say that the internet doomed the high street, I’m not

sure that’s entirely the case because we didn’t have the internet back in the

80s, although there’s little doubt that the internet would certainly accelerate

and seal the fate of the high streets

decline in the future.

I think it all started with a

combination of things. A perfect storm of innovation and technology coming

together and the visionaries who embraced those early technologies and began to

wonder how life changing it could be in the next decade and beyond. Little did

they know just how much of a leap they were about to make.

|

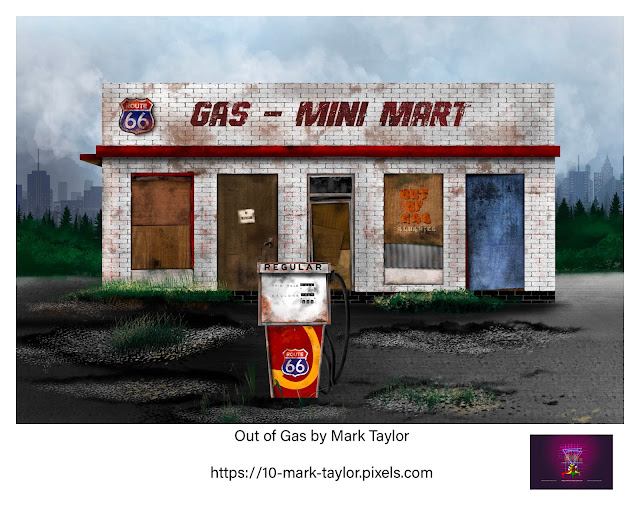

| Out of Gas by Mark Taylor |

Pre-web based systems were

undoubtedly another gateway to the future decline of the high street. They made

little to no real impact on local retail footfall at the time, but the seeds

had been sown, maybe even inadvertently, I’m not sure anyone in the 1980s would

have believed that the future high street would be accessed through a keyboard.

Those pre-web technologies

such as bulletin boards (BBS) which sprang up in the early 1980s, using platforms

like the Boston Computer Exchange (1982) facilitated online classifieds and rudimentary

electronic shopping. They mainly focussed on used computers and

tech-related products, which were still very specialist and very niche on the

high street. Transactions often involved phone calls or mail orders for

payment and delivery.

France’s Minitel (1982) and

the UK’s Prestel (1979) were videotex systems accessed through TVs and

dedicated terminals. They offered online

banking, classifieds, and limited online shopping through text-based

interfaces and proprietary protocols.

Both of these technologies

were niche, but the target audience for these systems were more likely to eventually

become the tech entrepreneurs that would take the seeds and push the technology

even further by creating emerging web based systems. Mainly in the guise of CompuServe

Electronic Mall (1985) and Freenet (1986).

CompuServe was one of the

first online shopping malls accessed through dial-up connections, offering

product information and ordering from various vendors. Payment often

involved pre-paid accounts or credit card orders over the phone. Encryption,

forget it, it wasn’t unusual to cut out an order form from a magazine and send

all of your credit card details through the traditional postal services.

Freenet was an early

peer-to-peer network allowing users to share files and

information, including software and digital art. Though not

technically e-commerce, it laid the groundwork for decentralized online

distribution models. This would become pivotal in the years ahead and

solidified the foundations for the internet we know today.

There were other developments

too, Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) was being used in the 1980s to

exchange purchase orders and invoices electronically and it is this that would

form the foundations for B2B e-commerce in later years.

By this time, online banking

began to emerge and this allowed customers who had invested in these early

technologies to do some very simple online tasks such as checking balances and

in some instances they were even able to make rudimentary transfers, something

that would later mature into the behemoths of banking systems that we see

today.

There were still plenty of

limitations and challenges that would stall the inevitable changes that were to

come, dial-up internet was slow, internet connections were much less prevalent

than they are today, and there were concerns around limited security especially

when it came to data security and online payment fraud, problems that would

exponentially grow over time as both the systems and the scammers matured into

more complex beasts.

These were barriers for

consumers and whilst those consumers were buying into the shiny new home

computer and PC thing which was being heavily advertised, the public were less

willing to engage with the online world because there was a cost barrier and to

be honest, people were generally either playing video games or using

productivity software. This was the golden age of Lotus 1-2-3, folks.

The majority of the mainstream

consumer population had little to no idea of the online world and when they did

catch a glimpse of it, that world was usually presented through clunky text

based interfaces or depicted on glass screens in a control centre as the

central focus of an action film. Remember, this was still very much rooted in

the days of early IBM, DOS, and very much pre-Microsoft Windows. There were no

user friendly interfaces, the interaction was often limited to typing on a

keyboard.

Overall, online commerce in

the 1980s was nascent and far from mainstream. But these early experiments and

technological advancements laid the groundwork for the explosion of e-commerce

that would happen in the following decades and I think that was the point that

the high streets fate was finally signed, sealed, but still as yet to be

delivered.

|

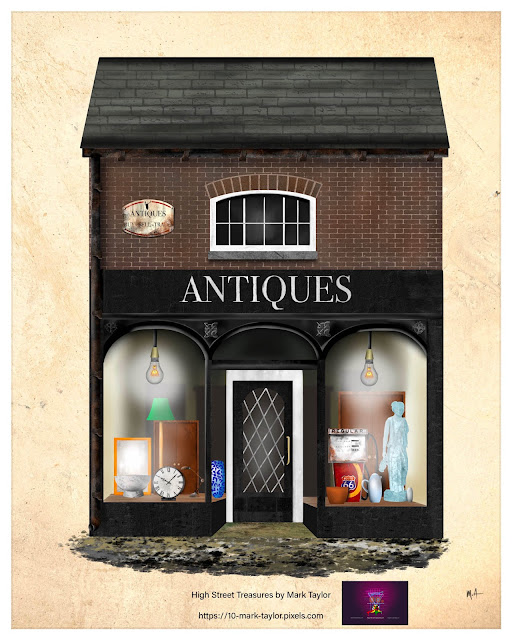

| High Street Treasures – Mark Taylor |

Television advertising in the

80s was on another level. In the decades since a lot has changed in the world

of TV advertising, its format, how ads would be targeted, the consumer

experience and there are huge differences not only between 80s and modern day

production quality standards but also in the content that ads were able to display.

Advertising cigarettes was a

huge source of ad-revenue in the 80s, I still remember the Marlboro ads, and in

the UK, the John Player Special ads that were adorned on formula one racing

cars. Tobacco advertising was banned in the UK and other territories over the

following years and TV advertising shifted away from the typical stereotypes

that had been used in the earlier years, but it still had a way to go to get

where we are today.

In the 1980s, ads would

typically run between 30 and 60 seconds, usually aired between scheduled

programming blocks and limited in number per hour. A 30-minute program might

have had ads at the start, halfway through and again pre-the next program, hour

long programs would generally see advertising every 15-minutes here in the UK,

in some countries ads were even more prominent.

There were limited channels

and viewers had nowhere to hide. It wasn’t until the mid to late 80s that video

recorders became much more mainstream and allowed consumers to record TV and

fast forward through the ads. In short, advertisers and ad-executives had a

captive audience, but as an advertiser you had little to no idea who those

people were.

The ad-men/women of the 80s

certainly had their challenges with this lack of trackability, but ads worked

perhaps because they were largely unregulated in the same way as they are

today. Content was genuinely, if not politically correctly, sticky. It

resonated because the messages were far less subtle than they often are today

and consumers were still largely discovering technology for the first time.

Catchy jingles, celebrity

endorsements, no influencers or con-fluencers as I like to call the majority of

them (oh my I do sound old and grumpy), and while I can say that I didn’t

always agree with the portrayed stereotypes, advertisers were bold enough to

push humour in ways that make todays ads sterile enough to avoid any possible

litigation. TV is rarely brave in the modern day.

Maybe because we also had

regional programming and entertaining TV that would be watched by millions of

people in real time, I think I would be minded to say that those ads probably

worked better than the hyper-targeted, highly focus group led ads that we see

today, albeit some of those 80s ads would be best left in the 80s or completely

forgotten.

Economic Restructuring…

The 1980s also witnessed

economic restructuring, leading to the decline of some traditional industries

and increased competition from overseas goods. This impacted local economies

and potentially reduced spending on non-essential items typically found on the

high street. Unemployment was significantly higher than it had been and there had

by then been a decline, particularly in rural England within industries that

had for hundreds of years been the providers of a stable income for generations

of the same families.

Coal mines had been shut down,

the steel industry was in decline, it was a decade of either decadence and

success or complete despair depending on what industry you worked in. An

inequality that had existed before was being amplified across communities and

this would eventually trickle into high streets up and down the country. Politics

played a hand too, but that’s a complicated story for another time.

|

| French Bread by Mark Taylor |

Beyond purely technological

factors, the 1980s witnessed a shift in consumer preferences towards

convenience, brand recognition, and value for money, which out-of-town shopping

centres and early online retailers aimed to capitalise on. Advertising was

becoming more powerful and the world was becoming exponentially smaller with

the advent of mobile phones, early websites and a growing awareness about how

the online world would provide the future of flying cars that we had been

promised in the 1950s and 60s.

People were ready to embrace

change and by the mid-80s, were also being encouraged to buy into the world of increasingly

more affordable technology. Home computing saw its barriers to entry removed

with the introduction of cheap 8-bit home microcomputers, and the rapid pace of

technical innovation began to get people excited for the future.

I often wonder how many of

those people, me included, figured that technology would eventually have such

an impact on everyone’s lives. The target audience at the time were mostly

living in the here and now, and many of them were wearing Swatch watches and

gaudy colours from United Colors of Benneton. Looking back, the 80s were very

much all about living in the now.

It’s important to note that all

of these these factors intertwined, The convenience of out-of-town centres was

partly enabled by improved transportation infrastructure, itself a product of

technological advancement. The rise of TV advertising and direct marketing

relied on technological developments in communication and changing consumer

preferences were likely influenced by factors like economic restructuring and

the overall cultural shift towards mass consumption led by the brands and the

marketing teams.

The 80s was the real

birthplace for mass consumerism, even I bought into it when I got my first

Filofax which I carried around but didn’t have either the responsibility or the

social life to fill in. One year later, that Filofax still had no entries, but

it was a free gift with a bottle of Drakkar Noir, an 80s aftershave that I

still wear to this day.

As I said earlier, it was a

combination of things that scuppered our Saturday afternoons bumbling around

the local shops. It was a perfect storm and a hive mind of innovation that

finally sealed the high streets eventual fate, but there is little doubt, that while

the fast pace of technological change in the 1980s wasn’t the sole culprit, it

was undeniably a contributing factor in its decline.

Beyond the economic impact,

the decline of the high street has woven itself into the fabric of social loss.

Independent shops and businesses, still to a large extent where they still

exist are the lifeblood of many communities but where they have been forced to

close, the closures also shuttered access to the personalised services and

unique products, and tactile buying experiences that they offered. Much of the

high street of the past was broadly, all about the experience and in part, the

human connections that could be made.

Retail was a by-product of

social interactions, as the decade matured consumerism began to reach fever

pitch. You could literally rock up on a street corner and sell toilet tissue

from a suitcase and people would buy into it and then it all crashed in 87.

|

| The Florist by Mark Taylor |

It’s not

all bad news for high streets, many communities are fighting back, championing

local businesses, hosting vibrant markets and many are really pushing the arts

and crafts movement. It’s not unusual to see communities working with local

authorities and landlords to transform vacant spaces into community hubs.

Innovative retailers are blending online and offline experiences, offering

click-and-collect services and personalised in-store consultations, so what

about the future?

For those

of us who might be looking at the past through rose tinted glasses and holding

out for a return of the high street as it was, I think we have to face the

inevitable that we are unlikely to ever see that type of high street ever

again. That’s probably not such a bad thing, the high street has had a history

of change for hundreds of years.

There’s

also a question as to whether High Streets are worth saving, I believe they

are, they remain critical to local economies and provide employment

opportunities without which economies would stagnate and decline even further.

How we go

about saving them is a bigger question, especially during times when finances

are stretched and you need more money to buy less. High streets have become much more complex in

how they’re made up too. Multiple landlords, much more stringent regulation,

less footfall, in some cases perhaps because they’re also much less accessible

than before, and sprawling urban areas mean that high streets are further away

from where people live.

The high street’s decline is a

complicated issue with no easy answers, but there are pockets of hope from

centres that have been entirely reimagined, and where communities and planners

have been thinking outside of the proverbial box.

The narrative of decline is

different the world over. In Europe, many high streets have continued to

thrive, albeit in a reimagined way and mostly due to the strong social safety

nets and cultural significance of public spaces which afford some protection.

The problem for most regular high streets is that they don’t have easy access

to a Roman Coliseum to attract the crowds, most high streets are no longer the

destination, they’ve become much more passive and rely on passing trade.

In Asia, there is a very mixed

story of booming economies in major centres leading to continued growth and

development, but there are also stories that mirror the plight of declining high

streets elsewhere. In the US, some high streets and malls have been finding

success in mixed-use developments combining entertainment, retail, offices and

housing, bringing communities back into the areas that have previously been in

decline.

Mixed use spaces that offer

this kind of integration alongside experience driven retail with a community

focus further highlights the need for traditional high street’s to adapt. They

demonstrate how high streets and public spaces can once again thrive, but it

requires planning and finance and effort to make it happen.

Perhaps the answer is that the

high street has gone and its replacement could be born out of any public space.

Does the high street need to be as linear as it once was with rows of streets

filled with shops and restaurants, or could it be reimagined completely and be

placed right on everyone’s doorstep?

That’s a question that many

previously declining areas have faced and answered, and they’ve seen huge

transformations not just within the local economies, but within the community

too with many also seeing dramatic reductions in crime rates. Art has played a

massive role in many of the most successful projects and with fewer local

authorities being in a position to continue funding arts programs and projects,

it might just be up to the art community to step up and help put some of these

wrongs to right.

- Murals in East New York, Brooklyn: A

2012 study by the University of Pennsylvania found that murals painted in

East New York were associated with a 27% decrease in shootings compared to

nearby areas without murals. The study suggests that the murals

fostered community pride and ownership, leading residents to be more

vigilant and report crime. - Creative Time in Staten Island: The

“Art of Resilience” project in Staten Island, New

York, used temporary art installations to engage residents in the

post-Hurricane Sandy recovery process. The project is credited with

reducing crime by creating a sense of community and purpose. - GraffitiGardens in Chicago: This

initiative reclaims abandoned lots in Chicago by turning them into vibrant

community gardens adorned with street art. The program has been shown

to reduce crime by deterring vandalism and creating a more positive

atmosphere.

• Balboa Park, San Diego: The revitalisation

of Balboa Park in San Diego, including art installations and cultural events,

has been credited with attracting tourists and businesses, generating billions

of dollars for the local economy.

- Cultural District in Cleveland, Ohio: The

creation of a cultural district in Cleveland, Ohio, featuring

art galleries, museums, and performance spaces, has led to

increased property values, job creation, and tourism revenue. - Public Art in Chattanooga, Tennessee: The

installation of public art in Chattanooga, Tennessee, has been

credited with attracting businesses and tourists, and contributing to

the city’s economic revitalisation.

While these are positive

examples, the impact of art on crime and the economy is probably more complex

than this. It’s not always quantifiable and other factors such as economic

development initiatives and changes in the local population over time, can all

play a role.

There are also those who

consider community art projects leading to inevitable gentrification of areas pushing

property prices up and pushing out those on a low income, further widening the

gap between rich and poor. I think this is why it’s so critical for planners to

develop strategies with the community and local businesses rather than planning

from a distance which often means that communities feel fewer of the benefits.

|

| Old News by Mark Taylor |

- Murals and street art have transformed

public spaces and there are plenty of great examples that can be found on

Google’s Arts & Culture. https://artsandculture.google.com/

Public Installations: Sculptural installations, interactive artworks, and temporary

exhibits can spark curiosity, generate conversation, and create unique

destinations within the high street. Think Antony Gormley’s “Another

Place” on Crosby Beach or Yoko Ono’s “Imagine Peace Tower” in

Iceland.

Light Installations: Illuminating buildings, streets, and squares with creative lighting

design can create a magical atmosphere, attract visitors after dark, and

highlight architectural features. For example, the annual Lumiere festival in

Durham transforms the city into a wonderland of light. My nearest Cathedral,

Lichfield in Staffordshire, UK, is completely illuminated over the Christmas

period, attracting thousands of visitors each year. You can see it lit up right

here. https://www.lichfield-cathedral.org/news/news/post/615-the-lichfield-cathedral-light-show-is-back

The complexity of todays high

street often makes projects more difficult to manage. Local controls, planning

and zoning permissions, and multiple stakeholders in properties becomes a

bureaucratic nightmare, but once barriers are removed and communities begin to

engage with local businesses, authorities and landlords, the examples earlier

demonstrate how community projects can have a huge impact in reviving the

social fabric that has been lost in time.

|

| The Tea Rooms by Mark Taylor |

One of the best news stories

from the UK has been from the Nudge Community which you can find out more about

right here: https://www.nudge.community/whatwedo

The Nudge community believe that

the small things are important, the high street isn’t just about buildings,

it’s about people and making connections. Nudge aim to bring lasting change in

surprising and entertaining ways to build a strong local community and a strong

local economy.

Their mantra is to nudge local

people and businesses to be brave, creative and resilient and healthy,

supporting themselves and their community. Empty buildings in private ownership

have caused long term problems along Union Street for decades.

An important part of changing

the street is making sure some buildings are owned by the community. This means

they can use these buildings to create a street that meets the needs of local

people and more of the economic impact from changes they make stays in the

community.

There are plenty of other

examples of local communities taking a lead on high street recovery efforts,

pop up art galleries and studios that showcase the work of local artists.

Storefront for Art in New York have done this successfully which demonstrates

that even the worlds biggest and boldest cities haven’t seen some decline, but

whenever they have shown signs of decay there have been projects set up to turn

fortunes and communities around.

There are also examples of

community art workshops, with collaborations from local artists engaging

directly with those who might just buy into their work and we have seen great

examples especially since that horrible period we all experienced during 2020

and 2021. Artist-led regeneration projects that empower local artists to lead

the transformation of neglected areas through creative interventions, promoting

both community participation and placemaking. Projects like “Art

Block” in Baltimore and “Creative Time” in New York exemplify

this approach.

Of course it’s one thing

shouting loudly that we all want change, it’s an entirely different story when

it comes to actually getting people to buy into the concept of actually doing

something about it. Sure we can look to governments for answers, but I think

recent and not so recent experience of political interventions have

demonstrated better than anything else that community adhesion is difficult,

mostly, politicians can’t even agree with each other.

There has to be a combination of

intent, willingness, and leadership before you stand any chance of uniting

communities, I’m not convinced that with a few global exceptions, we would

necessarily find those qualities in modern day politics. I think, if we want

communities and high streets to thrive then the very people who are shouting

need to step up, no matter how little

they contribute, as long as they contribute something.

There are plenty of examples

here too.

- Community Murals: Involve

residents in creating murals that reflect their stories, values, and

aspirations, fostering a sense of shared identity and pride in the

community. Projects like “East Belfast Arts Project” and

“The Mosaic Mural Project” in Philadelphia stand as testaments

to this power. - Participatory Art Installations: Create

interactive installations that encourage collaboration and participation,

bringing people together in a shared creative experience. Think Candy

Chang’s “Before I Die” walls or Yoko Ono’s “Wish

Tree.” - Arts Festivals and Events: Organise

regular art festivals, street performances, and creative events within the

high street, attracting visitors, showcasing local talent, and injecting

vibrancy into the space. The Edinburgh Fringe Festival and Notting Hill

Carnival are prime examples.

Sometimes it’s problematic to

quantify how some of these more creative interventions contribute to the local

economy, but when I walked through my local town centre’s craft market last

year the local adjoining shops were definitely busier than on any other day,

car parks were full and there were clearly people attending who had travelled

into the region.

Art tourism attracts visitors,

Liverpool’s Tate Gallery is a semi-regular haunt of mine, it’s little over an

hour away and I always make time to walk through the local community to enjoy

coffee at an independent coffee shop whenever I make the visit.

|

| The Last Slice by Mark Taylor |

If communities want artists to

engage, the best way in my own experience is to make affordable studio space

available, host markets that promote the local arts scene rather than importing

art from other regions, and it’s vital that businesses collaborate with artists

and both parties remember that collaborations are two way relationships.

One area where I have seen

plenty of innovation around collaboration is where local retailers have

incorporated local artists work into window and internal displays. They’ve also

continued the theme by using a collaboration of the same local artists to create

the graphic design and branding elements and the best examples of this have

elevated the consumer experience and provided a very unique look and feel to

the business.

The barriers to becoming a

professional artist and making a living wage from your creativity are many and

varied. It’s entirely possible to create art out of anything and someone

somewhere will find value in that work, but if you want to express your

creativity using equipment that you might not as yet be able to afford,

becoming an artist is very much a chicken and egg paradox.

This is where community led

maker spaces have become critical to the success of local creative sectors.

Their unique combination of resources, community, and innovation can be

powerful tools for infusing new life into stagnant local economies.

By providing affordable

workspaces and access to equipment, Maker Spaces offer access to tools,

machinery, increasingly 3D printer farms, and other technologies that aspiring

creatives and entrepreneurs might not otherwise be able to afford.

Maker spaces are excellent at

encouraging a culture of innovation and collaboration. The community led

environment brings together creatives of all disciplines and skills and they do

tend to become hubs of shared expertise with plenty of mentors and peers

willing to share their skills. One example I looked at last year also had

members of the local business community sharing their business development

knowledge with each other and those businesses would then collaborate with

local makers to create bespoke local arts and crafts which were then sold

exclusively in the community.

Maker Spaces also tend to be

hotbeds of prototyping and product development, if something can be designed to

fill a local need quickly, it’s far quicker to cut out the logistical headaches

and supply chain issues by keeping everything confined to the local area

wherever it’s possible and that links perfectly to the green agenda which can

in itself often lead to grants opportunities.

The most successful Maker spaces

can also develop tomorrows local workforce. Offering workshops and training

programs, Maker spaces can provide training in various technical

skills, including digital

fabrication, welding, woodworking, and

electronics, creating a more skilled workforce and attracting new

industries.

They can promote local

manufacturing and production by facilitating small-scale production and

encouraging the use of local materials, contributing to a more resilient

and self-sufficient and critically, a more sustainable local economy.

They’re also great for emerging

technologies and industries. Maker spaces can act as incubators for new

technologies, such as 3D printing and robotics, attracting investment

and fostering the growth of future-oriented industries.

|

| A Stick of Blackpool Rock by Mark Taylor |

- Creating new retail opportunities: Maker

spaces can host markets and events showcasing locally made

products, attracting customers and generating income for makers and

artisans. - Encouraging collaboration between makers

and local businesses: Partnerships between makers and

established businesses can lead to innovative products, unique retail

experiences, and increased foot traffic in local shops. - Boosting tourism and economic

diversification: Maker spaces can become tourist

destinations, attracting visitors interested in unique

products, workshops, and demonstrations, diversifying the

local economy beyond traditional industries.

Personally, I can’t think of a

downside to a Maker space so long as you can ensure bold leadership, a

willingness and intent to engage with the wider community, and an ambition to

work with the entire community. If you are setting a maker space up, you also

need someone to sell the vision to the local community and perhaps just as

importantly, to local businesses and education providers. They are

all-encompassing, the best will have partnerships and a thousand moving parts

in the background and they will have landed the right messages with the

community, they will have also done the outreach work and fostered champions to

spread the word.

Maker spaces foster a sense of

community by offering a space for people to connect, learn, and

create together, encouraging collaboration and social interaction. That

means that you will want to engage with local government and you will need to

onboard local education providers because there is a real opportunity here to

promote further education and STEAM learning, vitally important for tomorrows

economy.

Engaging young people in the

maker experience can spark an interest in science, technology, engineering and

arts, the exact roles that build the foundations of any economy. Young people

need to be encouraged so that they can be better prepared for the needs of

future employment markets, particularly where people already in skilled roles

and heading rapidly towards retirement haven’t been able to pass on knowledge

and skills because of skills shortfalls. I call it community succession

planning, something that I think even globally, we haven’t always been great at

doing.

If you land this correctly, a

vibrant maker ecosystem can attract skilled individuals and

entrepreneurs, contributing to a more dynamic and diverse local

population. There are some caveats, mainly around how effective the leadership

is, ideally that should be someone with a modicum of business nous and

experience in the creative sector.

The rest is purely down to

ensuring that folks are committed to making the project work, and local

business stepping up and engaging. All of this might sound like an impossible

ask in some communities but where Maker Spaces have worked well it has usually

been in areas that have been forgotten about for years.

Further Resources:

Fixing the high street is

complex and it needs a coalition of the willing to make the changes needed and

drive local projects forward. Can we rely on cash-strapped governments and

local authorities to resolve any of this, I’m not sure we can despite how confident

I think we can all be that a thriving community heartbeat contributes

positively to local and national economies. To some extent it should be front

and centre of central/federal/state/local, government policy but apparently,

that’s not where we’re at in many places.

But as creatives, if there are

ways that we can collectively find to encourage more people to participate in

the sector then I think, in the name of art we should probably do something to

at least start the conversation.

Of course there will be

pockets of the population who have become disengaged with the concept of

community, that’s why strong leadership and a solid sales pitch are essential.

The walls of apathy need to be broken down and I suspect, this is going to be a

long slow process until someone shouts hey, this high street and community

thing might just be a great idea!

There is a question as to why

this should fall to creatives, I think the answer might just be that these kind

of problems often need a creative answer and besides, widening participation

and appreciation of the arts can’t really be a bad thing can it?

Where to buy Mark’s work…

You can purchase Mark’s work

through Fine Art America or his Pixels site here: https://10-mark-taylor.pixels.com You

can also purchase prints and originals directly. You can view Mark’s portfolio

website and see a small selection of his works

at https://beechhousemedia.com

All artwork and blog posts are

copyright Mark Taylor and must not be reused without written permission and

appropriate licencing.