Nelson Ijakaa, a Kenyan artist and advocate, has firmly established himself at the crossroads of creativity, activism, and technology. From his formative years in Nairobi to his current residency in Hamburg, Ijakaa has steadfastly championed the idea that art is not merely a means of expression but a transformative force capable of reshaping society.

Amidst the whirlwind of his residency, professorship, and activism, it felt like a real stroke of luck to find a moment to sit down and talk. I was very grateful to be able to steal him away from his commitments—particularly his role as an honorary professor at HFBK Hamburg, where he leads dynamic discussions on how technology shapes the visual arts—to hear his thoughts on augmented reality (AR), artificial intelligence (AI), and the power of art to interrogate power systems while amplifying African voices.

Our conversation meandered effortlessly, weaving through topics as vast as Kenyan Independence—central to the body of work currently available through Rise Art—to his mission to de-alienate contemporary gallery spaces. Listening to Ijakaa speak was nothing short of mesmerising; his words carried waves of knowledge, delivered with passion, conviction, and a certain ease that left me in complete awe.

I hope I can do justice to the depth of insight he shared during our discussion. To provide clarity, I’ve structured this feature into several sections, mindful of the complexity and sensitivity of the histories explored. I have tried my best to recount our discussion with care, with the support of Ijakaa’s guidance and edits.

The Political Backdrop of Nairobi and Its Influence

Nairobi has long been a city of contrasts: a bustling hub of culture and commerce shadowed by stark inequality and political unrest. Post-election violence in Kenya—most notably following the disputed elections of 2007 and again in 2017—has left deep scars. These events were marked by widespread violence, systemic corruption, and the brutal suppression of dissent. Nairobi, as the political and cultural epicentre of the country, became both a battleground and a space for resistance.

Social justice centres emerged in the city’s slums offering a place for marginalised communities to organise, speak out, and heal. These spaces were vital to Ijakaa’s artistic awakening, connecting him with the communities that would later inspire many of his works and his purpose as an artist. One of Ijakaa’s formative experiences was working near Mukuru, one of Africa’s largest slums, alongside his then mentor, Patrick Mukabi, at the GoDown Art Centre. Mukabi’s studio served as a refuge where people from all walks of life could create. “I was so moved by people’s circumstances,” he says. “I understood from my time here that this so-called successful country just doesn’t care for its citizens in a wholesome way.”

This proximity to Mukuru shaped Ijakaa’s understanding of art as a vehicle for social change: “I began asking myself, ‘What can I contribute to this conversation? What can I do to help?’” Amazed by the everyday resilience of Nairobi’s residents, Ijakaa set out to use his work to humanise and amplify the stories of those overlooked by society.

Maandamano II (oil pastels, acrylics, and image transfer, 2024, 97.5 x 60 cm) and The Crucifixion; (Maandamano) (acrylics and image transfer, 2024, 140 x 191 cm) are part of a recent larger body of work commemorating Kenya’s 60 years of independence. “In these pieces, I analyse and critique what it means to live in an independent Kenya today, contrasting the current reality with the spirit of optimism that characterised the immediate post-independence era. I draw on archival materials, including declassified documents and newspaper clippings, to construct a comparative narrative of the country’s lived experiences over the past six decades.”

The subjects of the portraits are young people from Anidan, an orphanage in Lamu, Kenya, where he taught during a residency in 2019. “To me,” Ijakaa emphasises, “these young, often forgotten individuals symbolise the state’s shortcomings in fulfilling its responsibilities to society.”

Shadow Art: A Light on the Invisible

One of Ijakaa’s most profound projects to date was his use of shadow art to highlight police brutality in Nairobi. In Kenya, the impunity of security forces is a recurring tragedy. Extrajudicial killings—where young men are arrested, disappear, and are later found dead—are not uncommon, especially in economically disadvantaged areas. “People had become desensitized to seeing bodies on the street,” Ijakaa remembers.

He used broken acrylic sheets, salvaged from Nairobi’s polluted rivers, to craft sculptures that cast evocative shadows. “These rivers are where waste is dumped—and, tragically, where people are discarded too. I wanted to draw that connection,” he says. The shadows formed by his installations were haunting, showing outlines of violence that viewers were compelled to contextualise. As audiences approached the work, sensors triggered lights that revealed the full narrative, creating an intimate, confrontational experience.

This tactile approach reflects Ijakaa’s belief that art should engage all senses to leave a lasting impact. “When people walk into a room and feel the art, not just see it, it stays with them longer,” he says.

Decolonising AI: A New Form of Activism

Today, now residing between Arusha, Nairobi and Hamburg, Ijakaa’s teachings focus on the ethics of AI and AR, specifically how these technologies can empower or exploit creatives. His nuanced position balances optimism with caution. He embraces AI as a tool for enhancing artistic expression but warns against its misuse, which he calls “new-age sweatshops”—a mechanism that strips artists of their agency and reinforces global inequalities.

“When used unethically, AI becomes a new form of colonialism,” he explains. He points out that AI systems, often built on biased datasets, perpetuate exclusion and exploitation. For example, during an earlier collaboration with Greenpeace on decolonising visual imagery databases, Ijakaa encountered the stark limitations of AI systems trained on Western-centric archives. “For example, if you typed ‘snow in Nairobi,’ you’d see an image of Paris,” he recalls. The project aimed to create more representative datasets, showing what Nairobi—or any other African city—might look like in imaginative or hopeful scenarios.

Confronted by the exploitative underbelly of AI, Ijakaa began to shift his focus to ensuring African creatives were recognised as active contributors rather than mere consumers. “We need big conversations to happen around colonialism in AI,” he says. “This isn’t just about art; it’s about equity in the systems shaping our future.”

Breaking Down Barriers in Art Spaces

While Ijakaa’s work addresses global systems of power, his advocacy often begins on a local level–no doubt inspired by his time at the GoDown Art Centre. Central to Ijakaa’s philosophy is the need to challenge the elitism that sadly pervades many traditional art spaces, advocating for greater inclusivity and accessibility. “I want to break down systems that close people off from art,” he says. “Art is for everyone, not just for those who can afford to navigate its gates.”

At his own exhibition in Nairobi, Ijakaa once arrived without formal attire, his dreadlocks loose, only to be stopped at the entrance by security guards who assumed he wasn’t on the guest list. After an awkward exchange during which he had to prove he was the artist, he was eventually allowed to attend his own show. True to Ijakaa’s empathetic and perceptive nature, it wasn’t long before he invited the guards into the exhibition space and personally guided them through the show.

When recounting this experience, he was careful to emphasise that the misunderstanding and assumptions were not the guards’ fault but rather a reflection of “the power structures at play in the art world.” Far from being disheartened, this moment further motivated him to ensure that any exhibition spaces he is involved with welcome locals who might otherwise feel unwelcome in gallery settings. The artist passionately aspires to include anyone and everyone who wishes to engage in dialogue, expressing: “I want people to look at the work I make and see universality.”

Toward a New Canon of African Art

It is for this reason that Ijakaa presses the need to rewrite the global art canon. Why, he demands, do figures like Picasso and Matisse still dominate art history while equally groundbreaking African artists remain obscure? It’s no wonder people don’t feel welcome in these spaces where they haven’t ever felt represented. “African artists have always existed,” he asserts. “It’s time for their voices to be heard and their art to be experienced.”

He envisions a future where Sub-Saharan African artists are celebrated as integral contributors to global art history, not just as exoticised footnotes. “My mission is to ensure the art of this region isn’t forgotten but remembered and used to educate others,” he says.

An Enduring Past

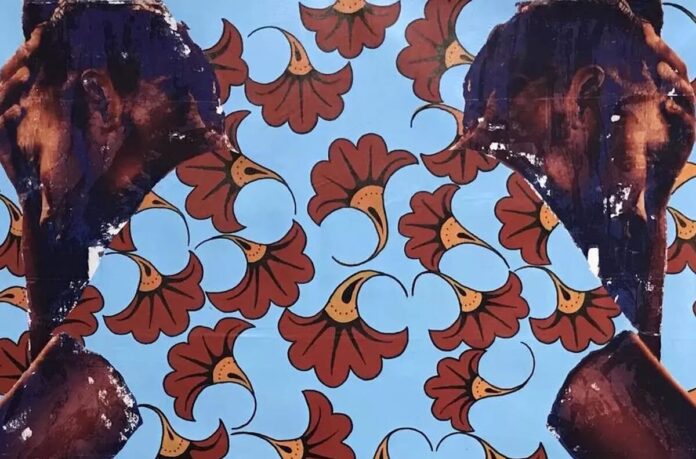

The process behind Miaka Sitini II, which forms part of a diptych, involved gathering newsprint and documents from the period immediately following Kenya’s independence. These materials, also used in Miaka Sitini III, reflect the hopes and dreams of a newly independent nation, along with its early challenges and complexities. In Miaka Sitini II, this archival content is juxtaposed with contemporary news, encouraging reflection on what has changed and what has endured over the past 60 years.

“The main figure’s image is transferred onto the canvas alongside the archival material, while the background is painted in dark acrylics,” explains Ijakaa. “Monstera leaves, commonly associated with tropical forests, surround the subjects. In this context, the leaves signify the complexity and obscured layers of the subject matter, partially concealing the image transfers and evoking the depth and mystery of a tropical forest.”

A Multisensory Future

Today, Ijakaa’s practice remains deeply multidisciplinary. From shadow art to video installations, woodcut prints to image transfer techniques, his work defies the constraints of a single medium. “There’s so much pressure to have a signature style, but I believe in evolving organically,” he says.

With Nairobi’s young, politically engaged artists pushing back against government repression, Ijakaa sees hope. The city’s gallery scene has become a space for challenging, provocative work, often tackling taboo subjects such as queerness and systemic violence. “The creative output of this season is meaningful,” he says. “It’s a reflection of the resilience and spirit of the people.”

As Nelson Ijakaa continues to push boundaries in art and education, his work reminds us that creativity is not just an act of self-expression but a catalyst for change. Whether he is decolonising AI or amplifying the stories of Nairobi’s marginalised communities, Ijakaa is reshaping the world’s understanding of what art can—and should—be.