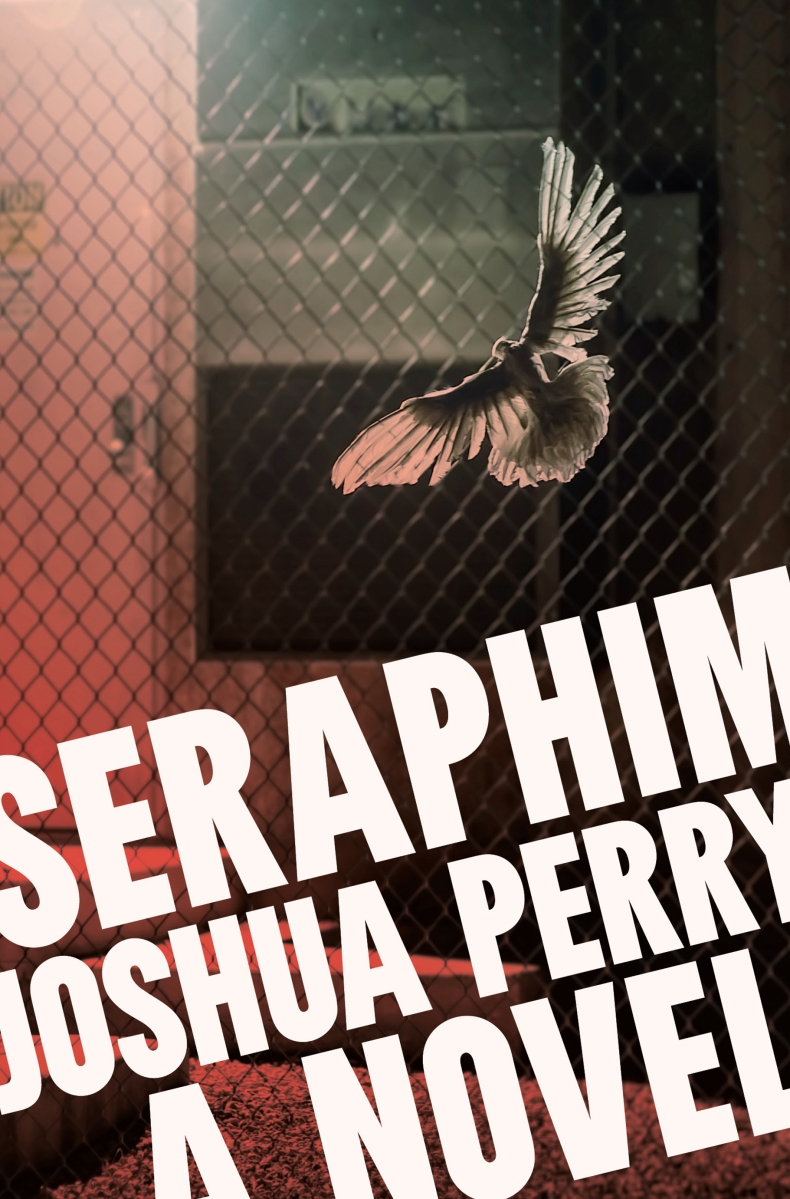

SERAPHIM

Joshua Perry

Melville House (mhpbooks.com)

£16.99

Buy a copy from your favourite independent bookshop

When 16-year-old Robert Johnson confesses to the murder of a minor local celebrity, he finds himself in the care of Ben Alder and Boris Pasternak (really), public defenders who specialise in helping children. Ben is also defending one Robert McTell, who happens to be the younger Robert’s biological father, though he decides to keep this fact from both clients. Ben is convinced that the younger Robert is innocent of the crime to which he has confessed and, with the help of Boris, sets out to find who really killed Lillie Scott. As the case garners attention, Ben finds himself dealing with McTell, who is determined to sacrifice himself if it will keep his son out of jail for the rest of his life. Ben, torn between the two, must decide who to save, while his investigation into the son’s life leaves him with more questions than answers.

Joshua Perry’s Seraphim takes us to New Orleans in the aftermath of 2005’s Hurricane Katrina. Neither Ben nor his partner Boris are native to the city, both new arrivals since the devastating natural disaster. They have seen their fair share of youngsters coming through the courts, and have some understanding of the deeper social destruction caused by the hurricane, a destruction that goes beyond the visible structural damage. They have encountered Robert Johnson before, so it’s no real surprise when he turns up again, though a murder charge seems out of character for the boy they both know. They begin to investigate, while attempting to quash Robert’s confession on a technicality. The investigation leads Ben to Memphis, where Robert and his family lived in a motel for months following the devastation of New Orleans, and where he first encountered trouble.

Joshua Perry was a New Orleans public defender for ten years, and it shows in the characters of Ben and Boris – there is a gritty realism to these characters, and the youths that they encounter on a daily basis. The pair have become fast friends, despite being very different people – Ben is quiet and awkward, while Boris is outgoing, good with women and with the kids who end up on his docket. The close relationship that the men share comes across in the conversations they have, trading quips and insults in the comfortable way of old friends. Perry’s mastery of dialogue is second, perhaps, only to Elmore Leonard; these sections are sharp, rhythmic and feel like real conversations, the kind of conversations we might have with our own friends. This goes some way towards helping embed us in Ben’s mindset, which is important for the story that Perry has set out to tell.

The author does a great job of evoking New Orleans, a city in recovery following the events of August 2005, when Hurricane Katrina devastated large sections of the city. Most of the kids whose cases come across Ben and Boris’ desks come from the poorer sections of the city, those areas that were most affected by Katrina, and so we encounter kids who have been homeless, who spent days or weeks of uncertainty in the city’s Superdome, or in nearby cities in Tennessee, Alabama and Mississippi. As a man who spent ten years as a public defender in the city, he certainly has first-hand experience of what his characters might encounter, and it adds a certain realism to the story, offsetting the “magical” expectation we readers might have of the setting. Travels through the recuperating city show us wrecked houses, buildings with high water marks eight feet high and higher, plywood boards over doors and windows, painted Xs designed to help rescuers in the early days of the recovery operation:

The painted symbol, an X with numbers and letters in the blank spaces, was a rune of invitation meaning the house was open to him.

Overall, Perry captures the terrible beauty of this storied city, and sums it up in one simple sentence:

This city is beautiful not because it’s old and grand but because it’s decaying in front of you, the incarnation of time passing.

In Ben, Perry gives us a character struggling with his place in the world. Is he making a difference? Is he doing enough? And, perhaps most importantly, is he happy? The book is around half crime novel, half examination of the world through the eyes of this young man who would probably be considered privileged by the people with whom he has surrounded himself. In many ways, Seraphim is less about whether or not Robert Johnson is guilty, and more about the relationship between boys and their fathers. The obvious Johnson-McTell link aside, Ben also finds himself thinking about his own father, and finds himself lying to both of his clients about his own family, his fictional children Isaiah and Nehemiah helping him to feel closer to the two men whose lives are, to a certain extent, in his hands. He feels like a father figure to the younger Robert, only to discover that he is no substitute, when all is said and done, for the boy’s biological father, who is prepared to – quite literally – give his own life to save that of his son, a boy he hasn’t been particularly interested in up to this point.

Seraphim is a short but involved novel. There are a lot of ideas in this compact story, and Perry ensures that they all get equal airtime, whether it’s an examination of the city, or the people in the city, or the relationships between those people – relationships with others, and with the land on which they live – without the story ever feeling crowded or rushed. By the end, the reader will be less interested in the outcome of the case than Ben’s journey and, to a lesser extent, Boris’ journey. The relationship between these two men – more fraternal than filial – is a rollercoaster ride in its own right, but when they’re sharing the page and shooting the breeze, there’s no other company we’d rather be in. I’m intrigued to see whether Perry will revisit these characters in a second book and, if so, where it might take them: the book’s ending seems to close a door on the entire story, but there’s enough ambiguity to allow us to hope. For now, though, we should be grateful for the little time we get to spend with these three-dimensional, identifiable characters. Joshua Perry’s novel is the perfect bait-and-switch, drawing us in with the promise of murder, but ultimately giving us more than we bargained for. It’s a book that requires the reader’s full attention, but repays that attention in full, and with plenty of interest. Not one for the beach, but one of the better novels you’re likely to read this summer.