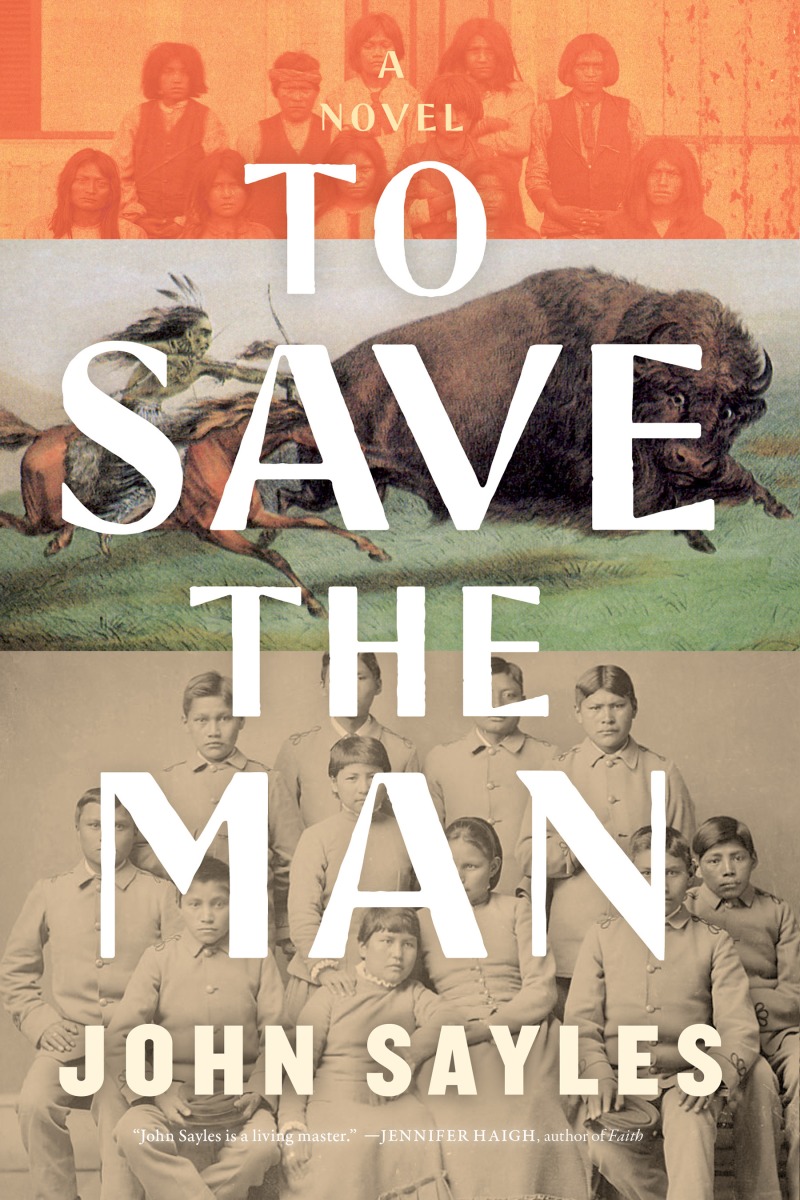

TO SAVE THE MAN

John Sayles (johnsaylesblog.com)

Melville House (mhpbooks.com)

£25

Buy a copy from your favourite independent bookshop

In September 1890 Antoine LaMere – son of an Ojibwe mother and a French father – boards the eastbound train. His destination is Captain Richard Henry Pratt’s Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, a military-style academy whose goal is to teach American natives the way of the white man. Rumours abound about the “ghost dance”, members of the native tribes dancing and chanting and claiming visions that prove the Creator is about to return the buffalo to the Plains, raise the Indian dead, and destroy the white people. As Antoine settles into the school, making friends – and even falling in love – federal troops are being deployed onto Lakota land, an action that will result in the infamous Wounded Knee Massacre and the death of legendary and revered medicine man Sitting Bull. Antoine and his friends must decide for themselves: to continue on the white man’s path, or to find a way to return to their tribes and take up arms against their oppressors.

“I reiterate that civilization and savagery are habits,” states Captain Pratt, “which can be learned and unlearned. And the first step for the Indian in that learning process is to hold his own land as an individual.”

Captain Richard Henry Pratt was a real person, a veteran of America’s Civil War who did indeed found the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania in 1879. John Sayles weaves a story around this historical figure, and the real massacre at Wounded Knee as the nineteenth century moved into its final decade, peopling it with fictional boys and girls, but seemingly keeping it as real as possible throughout. Pratt, by all accounts was something of a progressive, believing that everyone is created equal and that, regardless of the colour of your skin, no man had the right to any power over any other man. His hope was that the Native Americans that he took under his care would eventually own land and transact business and generally be useful members of society. But when you dig deeper, it becomes clear that while Pratt doesn’t care about race, he does have a very fixed idea of what civilisation should be, and that only the white people were doing it right. His most famous axiom, from which the book’s title is drawn, “to save the man, we must kill the Indian,” shows clearly what he is hoping to achieve, and we see this immediately as Antoine and those he meets on the long train journey east enter the school: they must speak only English, wear a uniform, forget the customs of their families and people; in short, they must become white in everything but skin colour.

Sayles presents his story from a number of points of view, including several of the schoolchildren, the teachers and disciplinarians hired by the School, journalists camping out on the Lakota reservation as tensions build and all-out war looms on the horizon, and Richard Henry Pratt himself. It’s an engaging story as we watch these young people settle into the school year, forming relationships between them. Some are more impressionable than others – Antoine, for example, perhaps helped by the fact that his father is French, making him almost halfway white, or perhaps because of his desire to spend time with Grace – while others – the aptly-named Trouble, for example – fight tooth and nail every step of the way. The school itself is an interesting setup, perhaps driven by Pratt’s military background, as the children are divided into “companies” and promoted through the ranks based on merit, becoming a series of small, self-governing groups. When word reaches the school of the massacre on Lakota land, it affects each of the students in different ways, and it’s surprising to see who will bury themselves in their studies, and who will flee the school under cover of darkness, westward bound. These are all characters who jump off the page, Sayles beautifully painting each individual in a way that lets us see their point of view (even if it’s a point of view with which we don’t agree) and sympathise with their plight.

To Save the Man is a well-researched, and well-written mix of fact and fiction that attempts to shine a light on a dark period of American history in a balanced and unbiased way. Sayles presents the facts, and the different reactions, and allows us to come to our own conclusions; this is not history written by the victors, but a thoughtful and balanced portrayal of the events that invites us to make up our own minds. It is something of a balancing act for the author, and his approach helps to sell it to us, the reader: rather than a dry factual retelling of the events, Sayles brings it to life through a semi-fictionalised narrative that allows us to put the history into some kind of context, to view it as something that happened to real living people, rather than something that just happened.

John Sayles is clearly an accomplished writer, and To Save the Manis an important account of a dark stain on America’s history. It reads like fiction – gripping, emotional – while still being educational and informative. It is, in short, a fantastic read and is likely to feature heavily on lots of “books of the year” lists, despite it only being January!