*This is part three of an overarching story about music from its Biblical and historical origins until modern day, plus the cultural implications music has on young people. In part two, we spoke with CHH artist KJ-52 about his conversations with young people surrounding music and its content. Read Part One here and Part Two here. Part three of the series will look at the psychological impact music has on young people as we discuss with Dr. Caparrelli.

When it comes to parenting teens in the digital age, few topics spark as much confusion or conflict as music. Should you restrict explicit content? Ban artists whose messages you find toxic? Or let your teen explore freely, trusting they’ll figure it out?

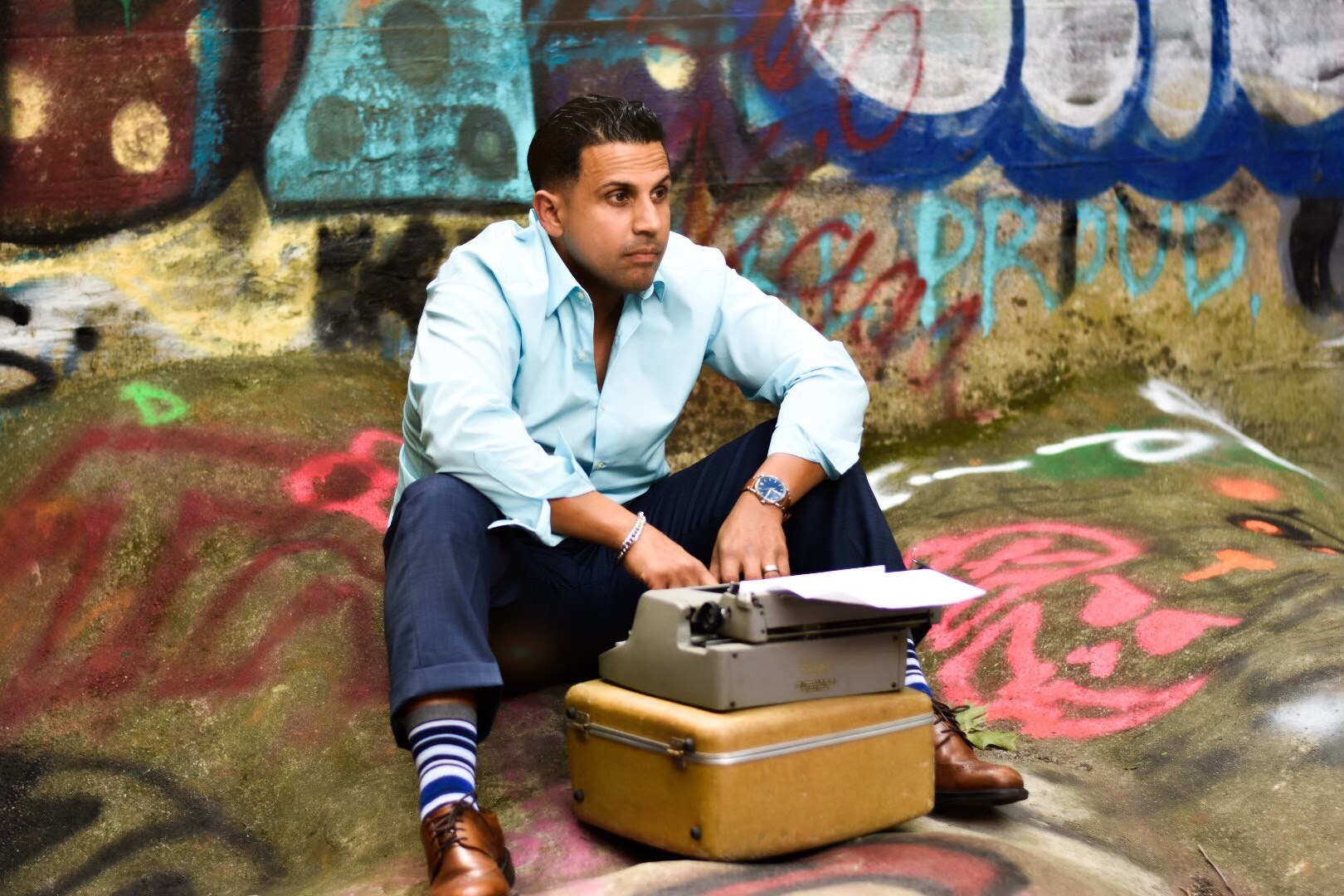

Dr. Michael Caparrelli, a former pastor with a PhD in Advanced Studies in Human Behavior, offers a refreshingly thoughtful approach. His advice? Stop drawing hard lines and start asking better questions.

“It’s better for the child to discover [the answers] rather than for the parent to declare it or demand it. The only way to discover is to ask those questions and help lead them to the answer,” Caparrelli says.

Caparrelli is an advocate of the Socratic method, a style of teaching through dialogue and inquiry, rather than instruction or rule-setting. He believes that when teens are given space to reflect out loud, they’re more likely to develop discernment that lasts into adulthood.

Curiosity Over Condemnation

In a world where access to music is nearly unlimited, trying to police what your child hears may not only be futile, but it might backfire. Caparrelli emphasizes the importance of curiosity and communication.

“Making rules without providing reasons is a surefire way to produce an undesirable outcome,” he explains.

Instead of banning a song outright, he recommends engaging your teen in a conversation: What draws them to this music? What do the lyrics mean to them? How does it make them feel?

This approach avoids the “because I said so” dynamic that often leads teens to rebel. Rather than moralizing or shaming their tastes, you’re creating space for mutual respect and better understanding.

When Music Gets Dark

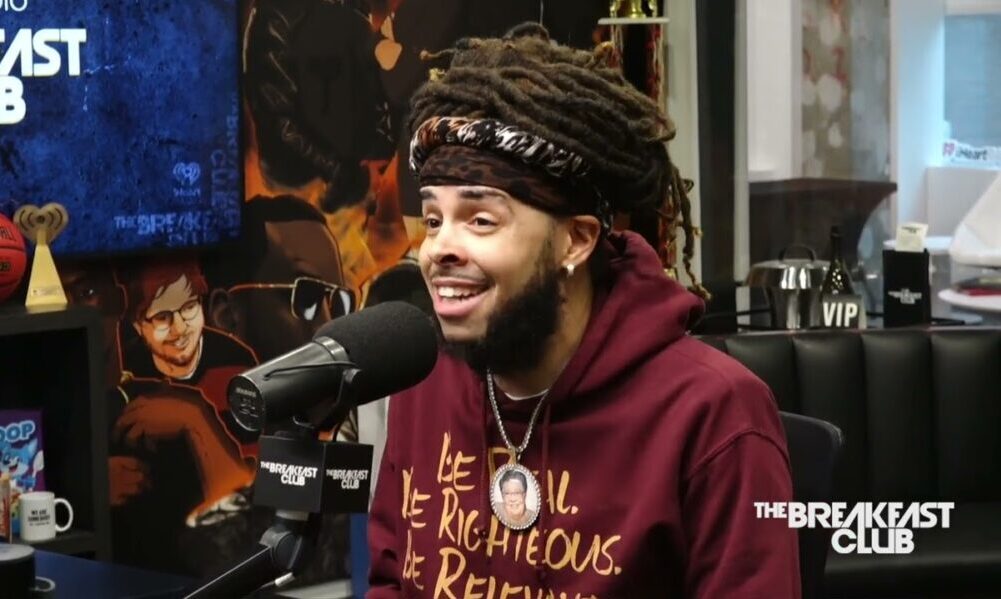

Destructive, or as rapper Dee-1 calls it, “poison music,” is music that is littered with profanity, degradation, and blasphemy.

Rarely is music itself the root cause behind bad behavior. Instead, music may reflect what a person is already feeling inside.

Marilyn Manson’s music was famously blamed for the killings caused by the Columbine shooters. His music may be known for its dark imagery and Satanic undertones, but Manson never said, “Go shoot people in your school.”

Caparrelli acknowledges that some music contains disturbing content. From violent lyrics to hypersexualized themes, today’s top charts can feel like a moral minefield. But instead of assuming that music causes bad behavior, he suggests a different framework.

“It’s a cathartic release,” Caparrelli explains. “If one has suppressed anger or emotion, that wants out. It’s not easy to release emotion as necessary. We rely on a variety of resources.”

Music, in other words, is often the outlet, not the instigator. A song might give language to pain or frustration that a teen doesn’t know how to express otherwise.

Caparrelli warns that this release can go in different directions. While some music helps people cope and reflect, others may reinforce harmful patterns of thought.

He references a cycle deeply rooted in cognitive behavioral theory:

“Thoughts affect feelings, and feelings induce behaviors. Positive content, positive thoughts, and feelings, which create positive action.”

This psychological loop is powerful. A hopeful song can lift someone out of a dark place, just as a song filled with rage or despair might nudge them deeper into emotional unrest. Caparrelli recounts a moment when a song profoundly impacted his own mindset.

“The song by Andra Day, ‘Rise Up’, comes to mind,” he says. “I was on the treadmill, and now my thoughts are centered on this idea of rising up.”

That emotional shift is not random—it’s biochemical. The music we listen to triggers neurotransmitters like adrenaline, cortisol, or oxytocin. These chemicals influence how we feel and, in turn, how we act.

Not Just to Feel Good—But Not to Feel Bad

For Caparrelli, one of the most misunderstood aspects of music is its emotional complexity. Yes, people listen to music to feel good, but also, sometimes, just not to feel bad.

“People are not just listening to music just to feel good, they are also listening to not feel bad,” he notes.

Young people will often say that a certain band or musician “saved my life.” The music they find during middle and high school may come to represent important moments in time that they want to remember. As teens grow into adulthood, they may get tattoos of their favorite lyrics, revisit the same album older and older, and one day drop a lot of money on tickets to an anniversary tour. But what is it about teens and their music that has the two so deeply attached?

In most cases, the message of the music brings the child or any person through a rough moment in life. Those songs or albums have music that conveys how the person is feeling and resonates with the listener. The audience then knows they are not alone in how they feel, and that feeling is something they never forget.

This dual function of music makes it both powerful and tricky. It’s escapism and therapy. It’s a distraction and processing. For teens navigating emotional turbulence, music may offer the only “safe space” they feel they have.

Brain imaging studies have found that music with sad themes is often experienced as pleasurable. Musicologists wonder if that’s because sad music tends to have a slower cadence and a rhythm that calms the body. Sadder songs often offer the listener an opportunity to reflect, which can be soothing.

Caparrelli is especially critical of adults who diminish the emotional intensity of adolescence.

“Any adult that tells a teenager, ‘You think it’s bad now, wait until you get older,’ is not really being honest. There’s no more difficult time hormonally, emotionally, [or] self-consciously…”

This statement is more than just a reality check. It’s a call for empathy. Parents need to recognize that, to a teenager, everything feels high stakes. That makes music more than just background noise; it’s often a lifeline.

The Takeaway: Ask, Don’t Assume

In the end, Caparrelli believes the best way to guide teens through their musical journey is by walking beside them, not ahead of them.

That means being aware of what’s trending, even if you don’t like it. It means being willing to explain, not just enforce. And it means trusting that asking the right questions can do far more good than delivering the right answers.

Music is emotional. It’s personal, and for your teen, it may be the soundtrack of their most formative years. As Caparrelli reminds us, the goal isn’t to control their playlist, it’s to help them build one with purpose.

This concludes the final part of the Music Culture and Impact series. Part one of this story focuses on the origins of music and how it relates to culture. Read it here. Part two focused on the conversations parents can have with their children surrounding music. It features insight from KJ-52. Read it here. The overall story was part of a shorter article that got published elsewhere. Shout out to Common Good Magazine for keeping my story alive and publishing part of it. Read it here.