by Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp

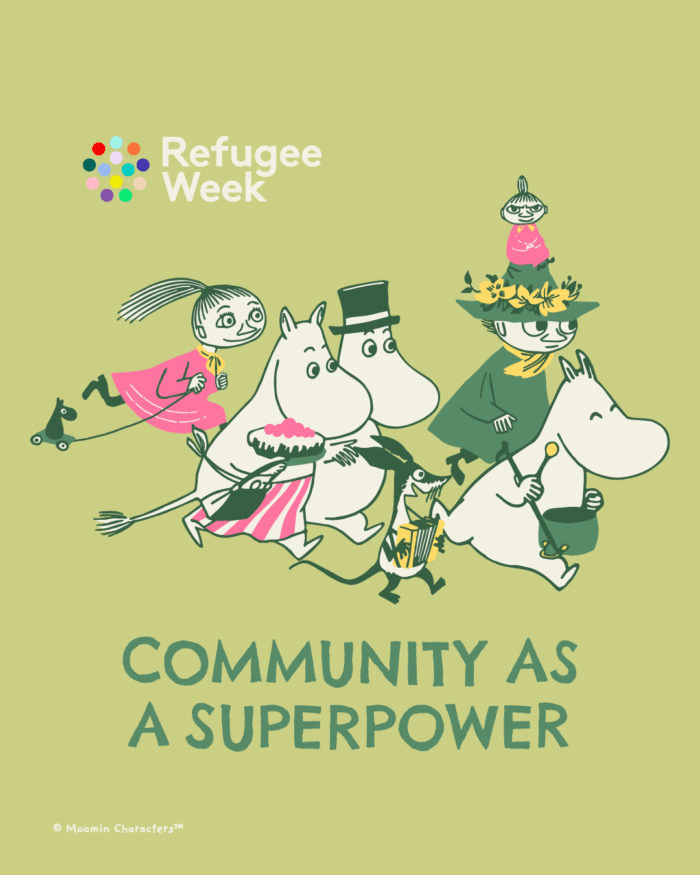

This year is the 80th anniversary of The Moomins and the Great Flood, originally published in Swedish in 1945 by Finnish artist, illustrator, and writer Tove Jansson. And this June the Moomins are the mascot of Refugee Week: a community-powered festival from 16-22nd June where everyone is invited to take part.

We asked five literary translators – some life-long Moominophiles and some who first set foot in the Moominvalley as adults – about that magic spark that has made the Moomins such a global, cultural phenomenon.

World Kid Lit: So, what is it about the Moomins that makes the characters so iconic and the stories so enduring?

Sarah Death: I think it’s to do with the interplay of the familiar and the unfamiliar. The wider Moomin family, including all its hangers-on, is the product of a unique imagination: free-ranging, wacky, even absurd; whereas the way they behave and interact is just like people we all know, so well-observed in terms of individual traits, family dynamics and social hierarchies. Psychologist, philosopher, educator, and artist – Tove Jansson manages to be all these things. The world she creates for her cast of characters is an appealing mixture of the alluring unknown and the comforting everyday.

Lola Rogers: The beauty of Jansson’s illustrations are an important part of what makes the Moomins special. Other artists’ renderings of the characters and settings can’t capture the vivid energy of Jansson’s own lines.

Eva Apelqvist: There is a sense of wonder in the Moomin Books that you rarely see in children’s books, or any books, that makes the stories magical. And the characters, oh, the characters. Not only do they put up with each other’s idiosyncrasies, they embrace them. The quirkier, the better.

Josephine Murray: I love the sense of the unexpected and absurd. At the beginning of David McDuff’s translation of The Moomins and the Great Flood, there’s this line “Here and there giant flowers grew, glowing with a peculiar light like flickering lamps.” Tove Jansson doesn’t labour the point when she introduces magical things, she just expects the reader to take them in their stride. The juxtaposition of the ordinary and the extraordinary is one of the things that makes you keep reading, and it provides humour too: in Moominsummer Madness when the Moomins’ house is flooded, there’s a great scene where they’re diving into the kitchen from the upper floor to retrieve the things they need for breakfast.

I also like Moominmamma’s homely wisdom: “Everything looks worse in the dark, you know.” She’s pretty unflappable and practical, and always has just what’s needed for any situation stowed in her handbag, from dry socks to medicine for tummy aches.

Trista Selous: The stories involve difficult emotions embodied in certain characters: the Hobgoblin is despairing, the Groke is terribly sad but still questing, the muskrat is grumpy and reads a book about “the uselessness of everything”, and while Snufkin’s free spiritedness may be great for Snufkin, it’s not so great for Moomintroll, who gets left behind when Snufkin leaves and misses him. There’s something very true and also accepting about all of this, allowing difficult feelings their space without their having to be healed, treated, denied or buried.

I think overall what is so great about the stories is that they allow things and characters to be partly unexplained, which leaves space that we can fill with our imaginations and feelings. At the same time, they tell us that everyone has their reasons, everyone is intrinsically interesting, and everyone is worthy of respect.

For Refugee Week 2025 in the UK, the theme is “Community as a Superpower” and the focus text is Jansson’s debut Moomin story, The Moomins and the Great Flood. But it’s not the only story that features disasters and peril, where the Moomin family welcomes incomers and refugees with open arms. What is it that gives the Moomins stories such a sense of hospitality, tolerance and community spirit?

Lola: I think there is something quintessentially Finnish about the way Moomin characters relate to each other and to newcomers. It’s not that they aren’t judgmental – they may strongly disapprove of someone, even disdain them. But before they judge, they first allow a person to show who they are and who they can be.

Sarah: Having immersed myself in Tove Jansson’s letters and therefore her life, I know that although not infrequently prey to self-doubt, she was fun-loving, gregarious and generous, with an approach to possessions and money that can best be described as ‘easy come, easy go’. It must have felt only natural to her to cast the Moomins – though not their whole intermittently maddening circle – in the same mould. As a family the Moomins experience their own share of uprooting and external threats, and perhaps it is this that makes them so ready to take in, or team up with, others suffering misfortunes or arriving as outsiders.

Which other Moomins stories work particularly well for modern times?

Lola: Thinking about The Fillyjonk Who Believed in Disasters has given me some consolation at this time when so many disasters have happened and so many more seem to impend.

Sarah: I’ve recently been translating a reworked version of Comet in Moominland undertaken by Tove Jansson in the 1960s. It has not appeared in English before and has some distinct differences from the edition that we currently know. This new edition will be published by Sort Of Books in late 2025 or early 2026. I don’t want to give too many spoilers but, as in various other of the Moomin books, looming disaster in the natural world can feel urgently relevant in the environmental crisis of today. One can’t help being touched by Tove’s illustration of a crowd of creatures escaping from their seemingly doomed homes, a raggle-taggle band of refugees struggling along with their children and belongings.

Lola, you translate from Finnish and know Finland well. What is the lasting impact of the Moomins at home in Finland?

Lola: The Moomins are ubiquitous in Finland. They are beloved in their own right, and are also a source of Finnish pride because of their international popularity. Moomin series and movies are aired regularly on television and streamed online in Finland. Moomin plays, puppet shows, and even a ballet and opera, have been performed at theatres around the country. There are frequent exhibits of Tove Jansson’s Moomin illustrations in galleries and museums. I’ve seen Moomins on the street in Helsinki. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if there wasn’t a single household in Finland that didn’t have something Moomin in it – a book, a mug, a pencil, a reflector to clip to a backpack, a pair of pyjamas… The Moomins are everywhere. They are members of the family.

Jansson wrote the Moomins stories in Swedish in a country where Finnish and Swedish are the two official languages, and Sami is one of several officially recognized minority languages. Is there a Sami translation?

Surprisingly, there seems to be only one published Moomin book translated into Sami, the picture book Hur gick set sen? (in English as The Book About Moomin, Mymble, and Little My). I assume that’s because virtually all Sami children are fluent in Finnish or other Scandinavian languages. Sami children are entitled to be taught in Sami in the traditional Sami homeland in Finland, but the number who choose this option is very small, and most Sami children live outside the Sami homeland.

Which is your favourite Moomins story and why?

Eva: I think The Moominsummer Madness is probably my favorite, if I must choose. The scene where they discover the theater and all the props is so humorous and loving, not to mention magical. And again, it speaks to the constant state of wonder.

Lola: The Fillyjonk Who Believed in Disasters is one of the first Moomin stories I’ve ever read, and still a favourite. Like many of Jansson’s stories, it is about facing our worst fears. The Fillyjonk is living in a house that is more gloomy and less cozy than she expected it to be. She tries to alter that by filling it with her beloved knickknacks and heirlooms, but she has a foreboding that all her efforts will be destroyed by some impending disaster. Then the disaster comes in an enormous storm that does indeed blow out all the windows, breaking her precious belongings and eventually demolishing the house. But instead of desolation, the storm gives the fillyjonk a feeling of liberation and joy.

I love the story’s title. It implies that the possibility of disaster, of an event than will truly destroy everything and make life empty, is something a person can choose to believe in or not believe in. You can choose whether or not to worry about things beyond your control. And if drastic change does come, it rarely destroys you and never destroys the universe itself, which is a strange and profound consolation.

Sarah: I like the oddness of Moominsummer Madness, with its fiction-within-a-fiction aboard a washed-away floating theatre, and the bracing change of location experienced by the family when Pappa gets itchy feet in Moominpappa at Sea. I’m also fond of the opening scenes of Moominland Midwinter, in which Moomintroll unexpectedly wakes up and ventures out into a scary snowbound world while the rest of the household is still deep in hibernation.

Comet in Moominland spends a little too much time outside Moominmamma’s reassuring orbit for my personal taste, but having recently translated it, I now feel very close to it, of course. And I admire Snufkin’s philosophy of travelling light, enjoying beauty wherever you find it, and not weighing yourself down with possessions.

Trista: My favourite book is undoubtedly Finn Family Moomintroll, which was the one I first encountered as a child, and with which we introduced our own children to the Moomins. It presents most of the main characters along with a world that contains the marvellously magical Hobgoblin’s hat, which transforms anything that is put or casually dropped into it. When it completely transforms Moomintroll, the others don’t know it’s him – until his Mamma recognises him, of course! It’s surprising, amusing, slightly alarming, but still somehow reassuring, all at once.

Sarah, you’ve completed a new translation of Comet in Moominland as well as translating Jansson’s collected correspondence. Were there any surprises, delights or challenges in translating her writing for English readers?

Sarah: It’s been great fun but also slightly daunting to tackle a modern children’s classic and renew it for the twenty-first century while also trying to retain its elusive magic. I approached the project with some trepidation, because as we know, in adult life and as gatekeepers for a new set of younger readers, people remain very attached to the versions of classics that they grow up with.

Tove is a great inventor of new words and I have tried to emulate that, but like any translator stepping into an existing major franchise, I have had my instructions about elements and names I’m not supposed to change.

Overall, I’ve tried to find a balance between making things accessible to young readers and leaving them mildly mysterious. As a fan of Maggie O’Farrell’s moving novel Hamnet, I enjoyed the recent episode of the BBC Radio series This Cultural Life in which she spoke about her literary influences. She has been a Moomin devotee since a tough time in hospital as a child, and still rereads the books whenever she feels the need. I felt strengthened in my resolve not to spoon-feed the reader when she listed the primary writing lessons that she has drawn from Jansson as follows: it’s fine to start by leaping straight into the middle of something – even dialogue – with little or no explanation; and you should never underestimate your readers.

About the contributors

Eva Apelqvist is an author of children’s and young adult books, and a Swedish to English translator. Sarah Death is a prize-winning translator from Swedish to English with thirty-five years’ experience, and part of the unpaid management team at Norvik Press. Josephine Murray is a writer, journalist, French to English literary translator and Secretary to the PETRA-E Network of institutions which teaches literary translation. Lola Rogers is a literary translator from Finnish to English, and a founding member of the Finnish-English Literary Translation Cooperative. Trista Selous is a literary translator from French to English and teaches literary translation at City Lit. Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp is a language teacher, translator, publishing consultant, and the managing director of World Kid Lit CIC.

Explore the Moomin-themed Refugee Week Resources

Support World Kid Lit!

World Kid Lit CIC is a non-profit company that aims to bring diverse, inclusive, global literature into the hands and onto the bookshelves of young people. We rely on grants and donations to support our work. If you can, please support us at Ko-fi. Thanks!

![It’s Monday! What Are You Reading? #imwayr [2.21.22] – Books. Iced Lattes. Blessed.](https://som2nynetwork.com/wp-content/plugins/phastpress/phast.php/c2VydmljZT1pbWFnZXMmc3JjPWh0dHBzJTNBJTJGJTJGc29tMm55bmV0d29yay5jb20lMkZ3cC1jb250ZW50JTJGdXBsb2FkcyUyRjIwMjUlMkYwNyUyRmltZ183MzY0LTMzNngyMjAuanBnJmNhY2hlTWFya2VyPTE3NTM5NzIyNTgtNzQ2MCZ0b2tlbj0xODY4MmFmMTVmMjAwYTFi.q.jpg)