On Translating ‘The Cinderellas of Muscat’

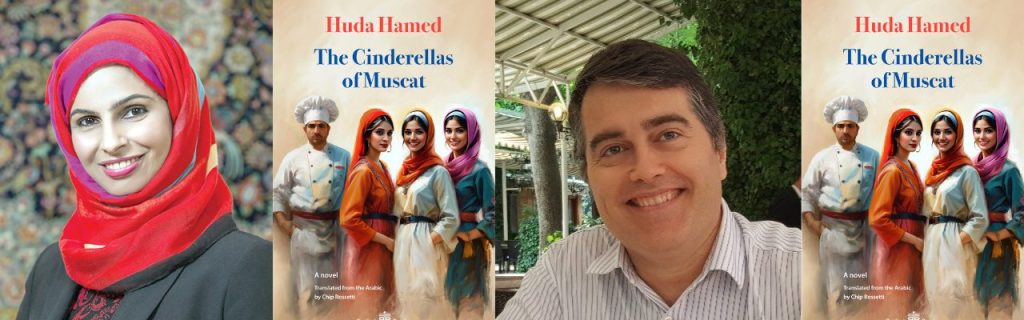

Tugrul Mende in Conversation with Huda Hamed and Chip Rossetti

This summer, Banipal Books published Huda Hamed’s The Cinderellas of Muscat, translated by Chip Rossetti. Here, Tugrul, Huda, and Chip talk through the Cinderella figure, the translation process, and the relationship between the author and translator. Huda Hamed’s answers were translated by Chip Rossetti.

Chip, you’ve done such a wide range of translations: from Sonallah Ibrahim to your work with the Library of Arabic Literature; from Diaa Jubaili’s telegraphic and evocative short-short stories to Reem Alkamali’s layered portrait of life in the 1960s Dubai. What drew you to Huda Hamed’s work, in particular The Cinderellas of Muscat? How do you decide “yes, this is a Chip Rossetti project”?

Chip Rossetti: For some books I’ve translated, I have happened upon the book myself—either by coming across it in a bookstore or reading a review of it, and been intrigued. In the case of The Cinderellas of Muscat, I got an email out of the blue from Samuel Shimon of Banipal, who asked if I’d be willing to translate an excerpt from a “beautiful novel” (his words) he had just read and loved. He sent me the opening chapter, set in Chef Ramon’s restaurant, and I was immediately taken with it. It’s the frame story that sets up all the tales that follow, but it made me want to read the rest.

I particularly loved the way the book opened, beginning not with the Cinderellas themselves, but with the jinn of Muscat, and how they fled the city once people began putting air conditioning and televisions their homes—noisy electrical devices that drown out the jinns’ voices. It was such an ingenious metaphor for the way modern technology overwhelms older, quieter traditions. When Banipal asked me if I would be interested in translating the entire book, it was an easy decision.

I think every translator—myself included—asks themselves generally the same questions before taking on the commitment of a new project. First, is this a work I love reading, and one I want to live with for a while as I translate it? And second: am I up to the task of translating this book? That is, do I think I can produce a translation that conveys at least some of the appeal of the original? For The Cinderellas of Muscat, my answer to the first question was definitely “Yes,” and I hope the answer to the second is “Yes” as well.

Cinderella is such a flexible character. Recently, she has appeared in the stories of Mustafa Taj Aldeen Almosa, and in the novels of Shahla Ujayli, and now in your novel. Huda, what do you think makes the story of Cinderella so instructive?

Huda Hamed: Reusing themes from global tales in contemporary novels doesn’t mean wholesale repetition. It generally requires a conscious creative act, where we delve into our shared human heritage. Incidentally, in our local Omani tradition, there is a story similar to that of Cinderella, although it differs in some respects and is quite closely tied to our customs and traditions. I should add that, as authors, we are generally not faithful to the original story, but instead, we turn it over or reinterpret it. With Cinderella, I was greatly interested in two important topics: first, the idea of transformation, since the women, exhausted by life, want to transform into princesses. They want to get rid of flabby stomachs, blotchy cheeks, cracked nails, split ends. They want this transformation, even if only for a day, either for real or by means of the jinn. Secondly, the idea of time—the hour of midnight that the female jinn appoints for them to go back to what they were, meaning that their transformation is limited and pre-determined. And they quickly return to their very normal lives.

But from another angle, the novel seems to contradict the story of Cinderella, because the eight women here aren’t looking for a prince to change their lives, as in the original story, which pictures a prince as the last resort for an overwhelming situation. Instead, these Cinderellas need storytelling and support in order to surmount their difficulties in life. A contemporary novel doesn’t necessarily have to follow the original story, but rather puts it into the form of a question: What if we could redirect it elsewhere?”

And for you, Chip—what aspects of The Cinderellas of Muscat were you most working to capture in your translation? Are there other books you likened it to, or wanted to put it in conversation with, as you worked?

CR: I’ve been wrestling with how to answer this question, and it occurred to me that my issue was with the word “capture,” which seems like the wrong metaphor for what a translator does. With my translation, I certainly hoped to convey the “livedness” of these characters, particularly the frustrations and aggravations that Huda recounts so well in the original, that contrasts with, and grounds, the magical elements of the frame story. Obviously, all these characters are women—wives, daughters, mothers, and in Zubayda’s case, a niece—so there is inevitably a challenge as a male translator to render them believably in English.

As to your second question, as I was translating, I kept thinking about Naguib Mahfouz’s Miramar as a novel that shares a common structure: both novels have multiple narrators, each one telling her story. In Miramar, the (male) narrators embody the different ways that Egyptians of various social classes and ages responded to the political and social changes of 1960s Egypt. Similarly, The Cinderellas of Muscat offers a kaleidoscope of the lives of contemporary Omani women—their experiences of marriage, motherhood, urban life, and infidelity, as well their rejection of cultural expectations about much of the above. Another novel it called to mind for me was Gharamiyyat Shari’a al-A’sha (Love Affairs of al-A’sha Street), by Saudi novelist Badriyyah al-Bishr, which includes multiple women protagonists, offering a cross-section of life in 1970s Riyadh.

If you had to picture the reader that this book was designed for, who would it be?

HH: I usually write for one reader: an imaginary one. One who is quite sensitive and is interested in psychological realism that is rooted in the novel’s characters. However mundane and normal the plot seems, she very much understands there is agitation deep beneath the surface. That is exactly what happens in the space of “show, don’t tell.” But once the book leaves my hands, the “death of the author” occurs, and readers sprout up from all over the place. And that’s why I can’t fall back on my gut sense about the text, since readers throw themselves into the task of giving it a dynamism that exceeds the fragile expectations I had when writing it.

How did you work on—well, we won’t say capturing, but evoking the different characters’ voices?

CR: Given the range of voices involved, it helped me to approach these various characters’ accounts as though they were individual short stories. The biggest challenge for me was in translating some of the younger voices, such as Sara, the narrator of the “Death Was Disgusted with the Old Woman,” and Alya, the youngest of all the Cinderellas, who is the eager audience for (and co-conspirator in) a schoolmate’s elaborate fantasies in “Alejandro and Ana Cristina.” Like much else about translation, consistency was key in conveying a character’s voice. To take Alya again as an example, part of the challenge for me was to maintain her child’s perspective even while her chapter offers us glimpses of the adult world through her eyes, whether the elevated romantic world of Alejandro and Ana Cristina or the lonely life her mother leads.

How much did you work together on this translation? Chip, what do you expect of a (living) author? Huda, what do you expect from the translator?

CR: I have been very fortunate to have ended up working with responsive, helpful authors when I write to them with a list of questions. Huda was very patient in answering my questions. I try to group my queries for an author into a few longish emails. Many times, a sentence or image that I can’t wrap my head around gets answered later on in the text. So by holding off on sending them, I can be sure I’m only asking questions that I am genuinely stuck on. Every author I’ve worked with has appreciated the work that goes into translation, and, in any case, I always convey that my questions for them are always with the aim of making sure I am grasping the finer points of their text, even if it’s not always possible to render them with the same level of nuance in English.

HH: Translation isn’t just a casual transfer of words, but a complex act, especially for those works emerging from deep within their local context. As they say, “Translation is a text reborn into a new life,” outside the borders of language and geography. A good translator goes beyond simply a transfer of meaning in order to give the text a different sensibility in the new language and culture. It’s like transferring a branch from its mother tree and grafting it into a new spatial and temporal milieu. And that’s why this book has deepened my connection with Chip Rossetti.

Huda, as the managing editor of a journal—and someone with a degree in Arabic literature—how would you describe the Omani literary landscape, and how does it differ from other places like Beirut, Baghdad or Cairo?

HH: Dealings with the Gulf in general, and with Oman in particular, have generally been at the margins of the main narrative. (And by “the main narrative,” I mean the major centers of the Arab world.) Yes, the cultural scene in Oman is different from its counterparts in Beirut, Baghdad, and Cairo, in terms of the circumstances that contributed to shaping its general outlook. The speed of the transformation—from life before oil to life after it—necessitated a good deal of balancing for Gulf societies, as they absorbed the changes that pumped fresh blood into the veins of their economies.

The rhythm of Omani culture is characterized by tranquility, far from noise, argument, and competitive activity, as opposed to those cities with their accelerated pace, which are generally the product of their political climates, social and economic changes, and a prolonged struggle over identities and freedoms. So we should not view things detached from the wider background that has shaped the characters of those cities, but rather study them in context.

Cultural activity in Oman is organized in an individualistic and often elitist way. It isn’t a public movement in which experiments jostle and fight each other. Nevertheless, a number of experimental works have been able to express themselves boldly and powerfully.

What are your favorite Omani novels? What are the Omani novels or short stories that you wish to see translated?

HH: I love the works of Jokha Alharthi, Bushra Khalfan, and Zahran Alqasmi. I consider them worthy of translation. There are also some new young names on the Omani scene that have begun the journey of having their talent blossom.

This book was also translated into Farsi. What has been the reaction of readers to it in Iran?

HH: I visited the Tehran Book Fair in 2024, and, to tell the truth, I was surprised by the crowd that had been curious enough to read an Omani writer like me. A large number of people attended the session that brought me together with my Farsi translator, Ma’ani Sha’bani. Most of them had read the novel and had questions about it, which was a thrill for me. Iranian women found, in The Cinderellas of Muscat, a mirror reflecting their own hidden pains.

A question for both of you: What are you working on now?

CR: I have just finished translating the Tuḥfat al-albāb wa-nukhbat al-aʿjāb, a text on marvels (ʿajāʾib) by a 12th-century Andalusi author, Abū Ḥāmid al-Gharnāṭī, with the English title Marvels and Wonders. I’m currently translating the 2021 novel, al-Bitriq al-Aswad (The Black Penguin), by the Iraqi author Diaa Jubaili, the protagonist of which is a member of Basra’s Afro-Iraqi population.

HH: I am writing a novel about a woman born in the 1930s, who at age nine contracts leprosy, which was contagious at the time. She is kept away from her family, to face an unexpected and extremely miserable life. She is burdened with grief, thinking that her family has abandoned her. The novel tells the story of the health situation in Oman in that era of intense poverty, and the changes that made their mark on every historical period, down to the woman’s deathin her eighties.