A time-honored tradition of malting grain, floor-malting isn’t something we typically see here in the States. But a select few craft maltsters have dedicated themselves to preserving what they see as a most sustainable, handcrafted method that delivers a more flavorful, high-quality product. Those like Blue Ox Malthouse in Lisbon Falls, ME, which, after a recent renovation, became the largest floor-malting facility of its kind outside of Europe.

In a sea of conventionally malted grains, Blue Ox has taken the proverbial bull by the horns, standing out with award-winning, consistent malts that range from a basic pale to a seaweed-smoked stunner. Amongst its many accolades, the malthouse recently picked up two gold medals for its Light Munich and Caramel 60 malts and Best of Show at the 2025 MaltCup awards, a premiere international malt quality competition hosted by the Craft Maltsters Guild.

The malthouse’s humble beginnings in Maine’s backyard have risen to expansive new heights. Dare we say they started from the floor…and now they’re here.

From Far-Away Madagascar to His Backyard in Maine

Photography courtesy of Blue Ox Malthouse

As an environmental policy graduate from Colby College, Blue Ox Co-Founder Joel Alex didn’t have the words to understand what he wanted to do with his life while in college.

Four months abroad studying environmental conservation and sustainable development in Madagascar, in contrast, showed Alex that he wanted to examine the needs of his community closer to home.

“It just didn’t feel authentic,” he shares, “going abroad to these developing countries and showing them how to use solar ovens or [telling them] not to cut down their forest floor.”

Alex wanted to come back and understand what he could bring to his own backyard in Maine.

After college, Alex became an environmental educator who taught ecology. He powerfully believed that if we applied ecological principles—reduced waste, more local decentralization of services, etc.—we could create more robust, resilient networks and services in society.

While doing a little homebrewing on the side, Alex started to get excited about the power of food to help create sustainable ecosystems. “We all have a deeply personal and immediate relationship to food,” he says.

But to come from preaching to practice would take a little longer.

While at a friend’s potluck, he started talking to Adam Chandler from Oak Pond Brewing.

Chandler mentioned a lack of local Maine-grown grain. While local hops were easy to access, anyone using a “Maine-grown” grain actually bought a blend that was first shipped to Montreal for malting before being sent back through a distributor in New York.

A light went off in Alex’s brain; he started researching.

“I realized that we were exporting millions, tens of millions of pounds, hundreds of millions of pounds, and then importing hundreds of millions of pounds of malted grain,” he shares.

Alex had found a missing piece: No one in his neck of the woods grew or malted local grain.

Could he?

The Mystery of Malting: I Can Do It Too

Without prior knowledge of malting or even the beer industry beyond homebrewing, Alex wondered if he could even start a company dedicated to craft malting.

While applying to grad school for food systems development, he started researching other craft maltsters across the country.

In the early 2010s, there weren’t too many—Valley Malt, Riverbend Malt House, and only a few others.

He realized something.

The backgrounds of those who started these companies varied—some were homebrewers, some environmental consultants, others social workers, and a few engineers.

Largely, no one came to malting from a strictly malting background or even professional brewing.

“If these people can do it,” Alex thought, “I can, too.”

By the time a graduate school accepted Alex, he realized he was way more excited about actually making an impact in the community than studying to do the same thing.

On April 23rd, 2013, with $2,500 in his bank account, Alex registered Blue Ox as an official company and Maine’s first malthouse.

We Started From the Floor, Now We’re Here

Photography courtesy of Blue Ox Malthouse

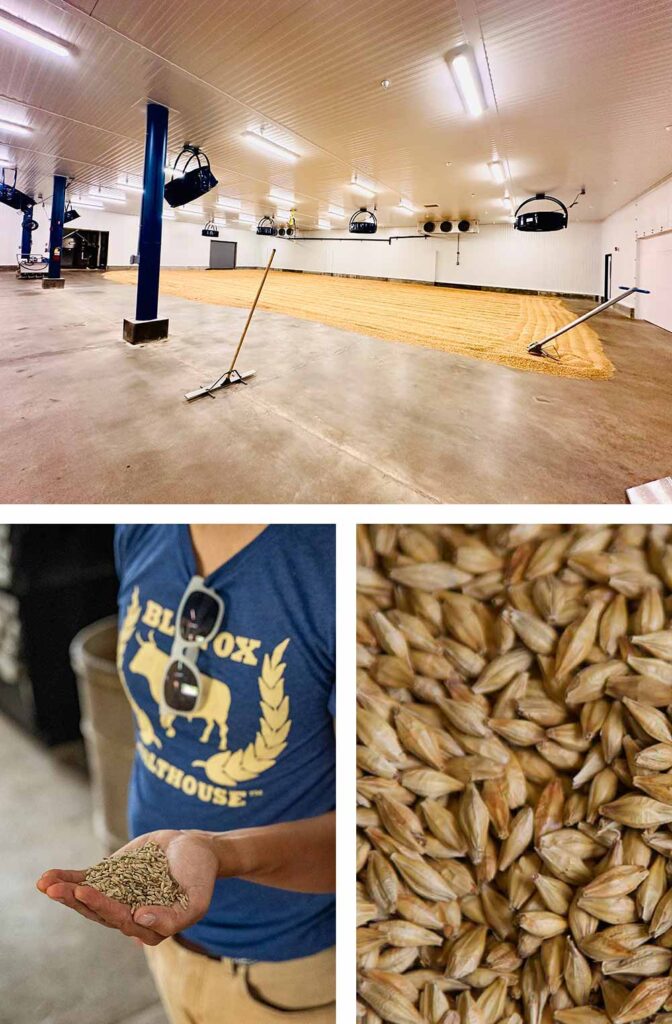

This past October, Blue Ox announced a completed expansion, making the Maine malthouse the largest floor-malting facility in the world outside of Europe.

The 20,000-sq-ft expansion quadrupled Blue Ox’s floor-malting capabilities.

From the very beginning, Alex chose to floor malt.

An old-school malting method, floor-malting involves spreading the grain or barley over large floor beds to steep and germinate.

During that time, people physically turn the grain to keep it cool and to keep the rootlets from matting together.

Floor malting is a hands-on, tactile, labor-intensive process.

So why would anyone do it this traditional way when a machine could achieve arguably the same thing without the additional human labor?

“I thought it made sense,” says Alex, for several reasons.

First and foremost, Alex always wanted Blue Ox to be an economic development tool, bringing jobs and revenue to the community.

One of the biggest reasons people don’t floor-malt is because it requires more labor than other malting methods. People need to rake the grain, scoop it, tend to it. “But part of my mission was to provide jobs for these rural communities,” explains Alex. “In some ways, that inefficiency actually leads to one of my goals for the business!”

Named after the legend of Paul Bunyan and his own cobalt bovine, Blue Ox is a “tip of the hat to Maine’s agricultural traditions, our culture, and our big dreams of making agriculture in Maine sustainable,” Blue Ox Director of Operations Ian A. Goering wrote to Hop Culture in an email.

Floor malting just made sense at Blue Ox.

Alex adds that it also differentiates Maine’s first malthouse, which would never win the price game with big commodity malt houses. “It would be silly to do that,” laughs Alex. “We needed ways to distinguish ourselves.”

The engaging, visual, hands-on method stood out in a sea of mega-mechanized malt companies.

“Every step of the way, people hold the grain, smell the grain, check on its conditions, and report to me,” says Blue Ox Malthouse Director Benji Knorr, who believes that care and quality sets Blue Ox apart. “Everyone is in tune with what’s going on with the grain in a way that I don’t think you get in an industrial setting.”

Alex never got into craft malting to make money. Before he started Blue Ox, the environmentalists’ Americorp salary paid him $12,000 annually. Instead, he wanted a company to bolster economic development, create good jobs, and develop a more sustainable loop for local breweries.

Plus, Alex fully believes that a hand-crafted, floor-malted grain just delivers more flavor and character.

If you’re floor-malting, during germination, people will turn the grain by hand three or four times a day.

Alex argues that the moist air circulating naturally through the grain develops a greater depth of flavor and character when compared with the conditioned air in a pneumatic, automated system.

Think about it like cooking a pizza in a conventional oven versus a handmade Neapolitan pizza oven. Effectively, the two vessels do the same thing—heat up and cook pizza. But one runs on gas or electricity while the other uses wood as fuel. With the former, you can set the temperature, pop a pie in, and essentially forget about it until it’s cooked. The latter, someone has to stand there constantly placing the pizza in a new spot to make sure that it cooks properly. It’s a more hands-on method that creates a different type of char and character.

With floor malting, you change how the product interacts with heat or moisture. According to Alex, those subtle shifts develop a unique flavor and quality.

What’s in the DNA of a Floor-Malted Blue Ox Malt?

Photography courtesy of Blue Ox Malthouse

With over ten years of floor-malting under his belt, Alex says the success of Blue Ox really boils down to one word: consistency.

Knowing he couldn’t compete on price, Alex says he needed to take local ingredients and create the highest-quality product possible…every single time.

“Consistency is key,” he reiterates.

To hit the highest quality with the lowest variance, Alex has invested most of his money into designing the malthouse to control variables like moisture and temperature.

Every step of malting has been carefully considered.

To start, Knorr and his team load the steep tanks with barley.

Knorr says the grain typically comes to Blue Ox with a twelve to fourteen percent moisture content, and, depending on the style of malt they’re creating, they aim to get up to a forty-three to forty-five percent moisture content. For instance, Knorr says they’re shooting for a forty-three percent moisture content for a pale malt.

Knorr does a series of steeps to hit those metrics, soaking the grain in tempered water—a set temperature—to induce germination.

“It’s not unique, but it is unusual,” says Alex. The tempered water brings “enormous consistency” to Blue Ox’s process right from the beginning, adding reliability downstream, too.

Knorr adds, “Making sure we have the same temperature water over and over again just increases the repeatability and consistency.”

After a certain amount of time, Knorr drains the water to let the grain air-rest—just cool air pulled naturally through the grain bed.

Knorr says they’ll do at least two steeps and rests until they reach the desired moisture content.

From there, the Blue Ox team takes the wet grain to a climate-controlled germination room, dumps it onto floors five to six inches deep, and rakes it to the same depth.

“We usually start at about three inches and grow to six after the grain has done its germination process,” Knorr explains.

Called casting, this manual step is unique to floor-malting.

While germinating, Blue Ox turns the grain four times a day, and employees measure the grain’s temperature at the start and end of each turn.

Most importantly, Knorr says his team physically feels the grain to help determine if it’s ready.

“You peel back the hull and rub the kernel between your fingers to assess how well modified the grain is,” he explains.

Once they determine the grain is ready, they load it onto an electric cart that delivers it through a conveyor system to the kiln, where it’s evenly distributed for drying.

Through drying, the grain achieves its variation in color and flavor, often the last step in creating the right style. “The lower-temperature curing results in lower-color malt, and higher temperatures results in those deep, darker-colored malts,” says Knorr.

The Rainbow of Malts at Blue Ox

Photography courtesy of Blue Ox Malthouse

Take a peek at Blue Ox’s products, and you’ll find a cornucopia. Everything from a brewer’s basic building blocks—floor-malted pale malt—to playing outside the sandbox—floor-malted smoked malts. And everything in between.

Knorr says he’s most proud of Blue Ox’s Floor-Malted Yankee Pils, which won two awards during MaltCon2024.

“It’s something people see as special,” he explains.

Likewise, Alex deems Blue Ox’s best-selling Floor-Malted Pale malt as one of his favorites.

It’s the backbone, the workhorse at Blue Ox.

With all of Blue Ox’s lighter malts, which Alex says tend to run a little lighter than normal, “there’s nothing to hide [behind],” he points out. “The fact that we can produce that really clean, well-performing grain with a strong background and depth of character in all the right ways is great.”

We tend to lean on hops far too much in this industry as the flavor-packed knockouts. And they are. But the importance of malt tends to get lost in that white (or should we say green) noise.

Tree House ran a series of beers last year—all American IPAs made with the same hops, yeast, mash temperature, condition process, and dry-hop volumes, but a different craft malt.

One version included Blue Ox’s Floor-Malted Pale.

After trying a few different beers in the series, Alex noticed that Blue Ox’s pale malt supported the beer’s hop character, giving more depth and extending the hop flavors longer.

“It was almost like the perfect IPA,” says Alex, admitting he’s not an IPA person per se. “That’s all to say I’m very proud of our pale and pilsner malts. I think they’re outstanding.”

And others in the industry agree.

Maine Beer Company’s Woods & Waters American IPA includes sixty percent of just Blue Ox Floor-Malted Pale; Blue Ox Floor-Malted Wheat, a pale, lightly-kilned wheat malt; and Floor-Malted Vyenna.

“It’s probably the cleanest beer we make,” admits Maine Beer Company Assistant Brewing Manager and Logistics Specialist Ben Cichanowicz, noting how wonderfully fresh this IPA tastes. “Their wheat is an exceptional product and makes super clean beers visually and taste-wise.”

Cichanowicz says Maine Beer Company started testing Blue Ox malt exclusively on its pilot system in 2015/2016.

Impressed with the initial trials, Maine Beer Company wanted to make a beer almost exclusively with Blue Ox malt.

Woods & Water debuted in 2017 and remains a full-time part of Maine Beer Company’s portfolio eight years later.

Cichanowicz sees many benefits of partnering with Blue Ox that extend beyond the bonds of the pint glass or can.

Local, Sustainable, Community

Photography courtesy of Maine Beer Company

“Right away, we’re injecting money into the local economy,” Cichanowicz says without hesitation. At Maine Beer Company, the brewery’s values include doing what’s right for the community, the environment, and the people. “Working with someone creating malt right in our backyard seemed like a great idea,” says Cichanowicz, who notes, “We’ve definitely proved that over many, many years!”

Before working with Blue Ox, Cichanowicz says Maine Beer Company ordered all its malts from all over the nation. In a month, truckloads of malt went across the country to the very tippy-top of the Eastern seaboard.

Blue Ox’s malthouse is just a twenty-three-minute drive from the Freeport-based brewery.

“Throughout the year, we’re saving thousands of miles just in shipping,” explains Cichanowicz, who estimates Maine Beer Company reduced delivery mileage from 15,000 to 6,500 miles yearly. “Being less than forty miles from our warehouse compared to 1,500 miles one way from another distributor is pretty drastic in cutting down on that carbon footprint.”

In a true testament to how much Maine Beer Company loves Blue Ox malt, they even replaced some of the grist in their flagship beer, Lunch, with Blue Ox’s Floor-Malted Light Munich, which recently won a gold medal at the MaltCup.

Cichanowicz says Lunch is eighty percent of what Maine Beer Company makes, so substituting a new malt wasn’t something they took lightly.

“We weren’t looking to make Lunch better,” he explains. “For us, if the substitution didn’t change the flavor profile and we could get it in our backyard, cut down on our carbon footprint, and make the beer more sustainable, local, and everything we preach, at that point, it seemed like a no-brainer.”

Then it goes back to that human element, that there are actual hands and humans behind Blue Ox’s malts.

“They care,” says Cichanowicz. “They’re brewers making good, quality malts for brewers.”

It’s impossible to put a price on having someone right in Maine Beer Company’s backyard who has the same values—sustainability, locality, and community—and also makes a high-quality, innovative product.

Or, as Cichanowicz says, “It’s really a blessing!”

The Smoking Malt/Gun?

Photography courtesy of Blue Ox Malthouse

While Blue Ox’s standard pale malt moves the most, Alex argues that their smoked products are their fastest growing.

“The market is hungry for innovation in beer outside of hops,” explains Alex.

As a part of the expansion, Blue Ox added a custom cold-smoker and a roaster to start fully flushing out its full smoked-malt lineup.

For instance, Blue Ox has a seaweed-smoked malt that has lived in Alex’s mind for years. The expansion finally freed up resources to make it happen.

The advantage is two-fold: a unique yet also sustainable product.

Alex wanted to find an alternative to smoking with peat, an incredibly well-known but environmentally irresponsible fuel source, according to Alex, who notes peat takes thousands and thousands of years to develop.

Blue Ox primarily uses wood for its smoked malt but also experimented with seaweed in “a quest for other sustainable fast-growing fuel possibilities,” explains Alex. Blue Ox sources its seaweed from Maine’s coast, making it sustainable, local, and tied to the maltster’s place in the community.

While Maine Beer Company doesn’t currently use these products, Cichanowicz finds the customizable option intriguing.

“I could go into my backyard, cut down an apple tree, chop it up, take it to Blue Ox, and they’d make an apple-wood-smoked something,” he laughs. “They always tell us that if we want a specialty smoked something, we just have to let them know!”

More Floors, Higher Ceiling

Photography courtesy of Blue Ox Malthouse

After over a decade in the floor-malting business, Alex says Blue Ox had reached its ceiling.

“We knew how to floor-malt; we knew how to do that really well,” he explains. “But we had been capacity-constrained on our old system for three or four years.”

The market demand for Blue Ox’s craft malt was high, but the old facility had reached capacity.

Having completed its expansion in 2024, Blue Ox’s new malthouse has two new floors twice as large as the previous ones, which are still available for use.

“That floor produced between five and six tons at a time,” explains Alex. “The new ones process about ten tons!”

Directed by Knorr, who also worked with a company called Maltster’s Advantage, Blue Ox’s expansion looked at every step of the malting process, exploring where they could improve. “I took the grain from the truck all the way through the facility,” he says.

For example, Blue Ox went from receiving 2,000-pound grain increments to truckloads of 5,000-6,000 pounds at a time.

Blue Ox designed everything with quality control in mind.

Malted grain bins are insulated and straight-walled, unlike raw grain bins, because different considerations are needed for each product at that stage.

Knorr and a small team basically built a new kiln themselves, assembling the pieces over three or four months.

And when it comes to packaging the grain right out of the kiln, Blue Ox upgraded from putting the malt in 50-pound bags to 2,000-pound ones.

To address the economy of scale and efficiency, Blue Ox installed power-assisted carts to help move the grain throughout the facility.

“We can pass those price savings onto our customers and help us stay competitive,” notes Alex, “and also, we can make our malts more easily accessible to our customers.”

When it comes down to choosing between a grain floor-malted from across the ocean in Europe versus one right in your own backyard, Alex hopes “it’s just obvious to work with us.”

Whether it’s award-winning floor-malted grain, innovative, new, sustainable seaweed-smoked malts, or something custom they haven’t even thought of yet, for the largest floor-malted facility outside of Europe, it seems like there just isn’t any ceiling.