Travel through the teardrop island to take an inside look at traditional arts and crafts in Sri Lanka.

Uncovering Traditional Arts and Crafts in Sri Lanka

Tucked between jungles and jade-coloured seas, Sri Lanka’s treasures aren’t always found in museums and palaces. Sometimes, they emerge from the flick of a chisel against wood or the slow glide of a stylus across a dried leaf of ola.

Traditional arts and crafts in Sri Lanka, or indeed anywhere, offer a slightly sneaky window to the past and how it brought us to the present. Less explicit than the history books but more in touch with how events and processes affect people and what they hope the future will bring.

Sri Lanka, the tear drop island south of India, has plenty. I love exploring them and trying to decode the influences from Buddhist devotion, South Indian migration, the European colonial powers, ancient trade routes and nature’s own art supplies.

If I’m feeling fancy, I’d say it’s watching history be worn, woven, carved, cooked, and sung.

And wonky. Or at least my efforts were.

So, travel with me as we explore not only the traditions of Sri Lanka’s arts and crafts but the ways in which you can join in too.

Disclosure: Abigail King travelled to Sri Lanka as part of a project with Sri Lanka Tourism. As ever, as always, she kept the right to write what she likes.

A Crash Course in the History of Sri Lanka’s Traditional Crafts

It’s always hard to know where exactly to begin but in the case of Sri Lanka’s, it’s good to start around two thousand years ago, with its role as a node along ancient trade routes and the long-standing presence of Theravada Buddhism.

When Buddhism arrived from India through King Aśoka’s son, the Arahant Mahinda, in the 3rd century BCE, it brought not only religious teachings but also architectural styles, ritual objects, and visual symbolism that required skilled craftsmanship. Temples and monasteries became the crucibles of creativity, commissioning murals, carvings, manuscripts, and ceremonial tools, many of which remain today.

The Kingdoms

Over time, different eras and rulers added their own imprint. The Kingdom of Anuradhapura (4th – 11th century BCE) saw the flourishing of stone carving and stupa construction. Polonnaruwa, the medieval capital, fostered bronze casting and the refinement of religious sculpture. Later, the Kandyan Kingdom, shielded by central highland terrain, preserved many indigenous crafts even as the coasts came under European colonial control.

The Europeans

The Portuguese, Dutch, and British didn’t just bring soldiers; they brought their own artistic forms. Lace-making from Portugal, batik and tile patterns via the Dutch, and printing presses and Victorian aesthetics under British rule. These were absorbed, adapted and reimagined, woven into local traditions with ingenuity and skill.

What about the future?

Crucially, many crafts were (and still are) passed down orally or through apprenticeship within families and guilds. How to gauge the softness of sandalwood, how to balance a chisel, or how to judge the readiness of a dye bath by smell rather than sight.

Today, the survival of these traditions is both fragile and remarkable. As in the rest of the world, Sri Lanka’s younger generations are migrating towards office jobs and digital work, although many rural communities still rely on craft as their livelihoods at local markets.

How many of Sri Lanka’s arts and crafts traditions will survive? As ever, it’s hard to say.

But what we can talk about today is what you can still find and take part in. As well as how you can bring a piece of Sri Lanka – and her cultural heritage home with you – in a non-exploitative way.

Traditional Handicrafts & Creative Arts

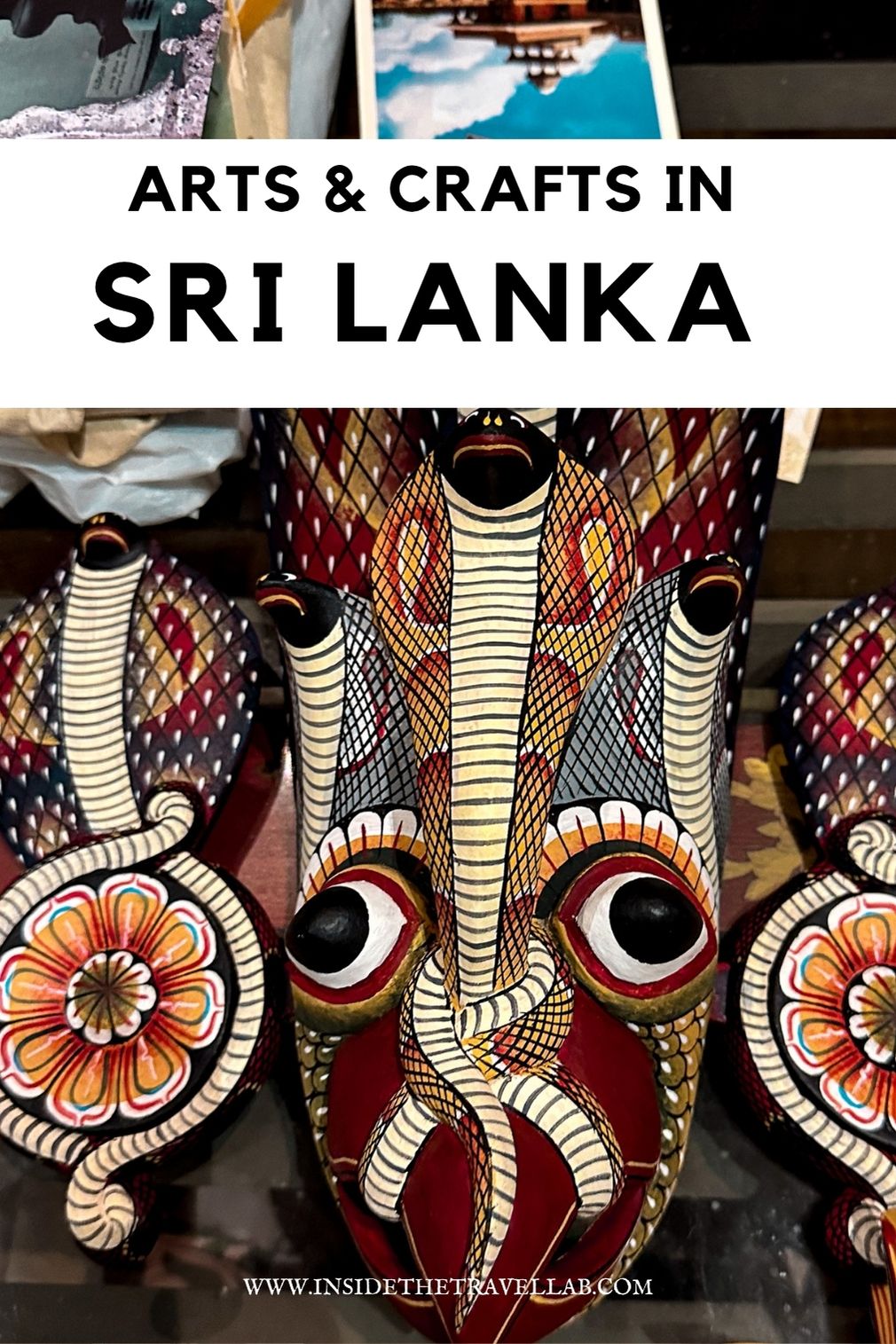

Wood Carving: Demon Masks

Here’s where I had the greatest chance to join in, carving my own demon mask from raw materials using traditional methods near the Galle Fort.

I met Janaka De Silva, an artist who runs workshops, at the Galle Fort Art Gallery. There, his two assistants, Chaminda and Harin, guided my chisel along the balsa to create my own handmade souvenir.

If that catches your attention, then in Ambalangoda, along the southern coast, the tradition of mask carving is particularly strong, with a museum and workshops open to visitors. The wooden masks with their theatrical designs are rooted in local folklore and used in exorcism rituals and devil dances. You’ll also find wooden carvings in temples across the island, where floral motifs and mythical beasts stretch across columns and ceilings, hand-carved by skilled artisans.

Calligraphy on Leaves: Writing with Light

In the serene shadows of Ridi Viharaya, a secluded temple north of Kurunegala, a magic trick takes place :calligraphy on ola leaves.

Using a metal stylus, scribes etch letters into the leaf’s surface, then rub soot or charcoal across the page to make the letters appear. The result is quietly beautiful but astonishingly durable. These scrolls can last for more than one thousand years, preserving religious texts, medicinal recipes and astrological charts.

As the monks told me, “Buddha was born in India but his scripts were written in Sri Lanka.”

Of course, it doesn’t quite work if you just grab a leaf and start scratching. They need to be boiled and fermented with herbs and baby pineapple, apparently, before being polished on a piece of wood with a bead.

The final trick is that you cannot use a table. To write a text, you must hold the leaf in your hand and remember what you have written. The words won’t become visible until the next stage of the process.

Batik Textiles

While scholars claim the wax-resist dyeing technique has roots in Indonesia, Sri Lankan artisans have made it their own. You’ll find plenty of traditional patterns that reflect nature: stylised peacocks, lotus flowers, and swirling waves.

In workshops around Kandy and Galle, you can watch the process unfold or even try your hand at it: painting wax onto cloth, dyeing in stages, and finally peeling back the layers to reveal a rich display of colour and form (or a shapeless smudge, depending on your skill level.)

We visited the batik cooperative linked to Malabar Hill near Galle which uses traditional techniques to make wall hangings, cushion covers and other decorative items. It is, quite literally, an immersive experience.

Today’s artisans build on the patterns of the past with new designs of their own. Check them out here:

Lace-Making

Introduced by Portuguese colonists in the 16th century, making lace has found a lasting home along the southern coast, especially in Galle. Here, women sit in shaded courtyards, twisting fine threads around bobbins to form delicate floral patterns.

Creating beeralu lace is a labour-intensive process, taking hours of work for just a few centimetres of lace, albeit with a distinctive design. But in a world of fast fashion and synthetic art forms, perhaps that’s no bad thing.

You can find out more about the lace making workshop at Moi Galle Fort here.

Pottery and Ceramics: Earth and Fire

Sri Lankan pottery is often practical: cooking vessels, water pots, urns. Yet practical doesn’t mean ugly.

Clay is shaped with respect, often in line with Ayurvedic beliefs, and used in rituals from weddings to almsgiving.

In the central village of Molagoda, the air smells of wet clay and woodsmoke. Here, families have shaped pots for generations, using the same hand-thrown wheels and open kilns.

You can observe potters at work or take part in a workshop, letting your fingers, if you’ll indulge me, dance through the ancient dialogue between earth and fire. And you’ll have some clay pottery to take home at the end of it.

Jewellery and Gem Cutting: Beauty Below the Surface

Sri Lanka’s name has long been synonymous with precious and semi-precious stones, especially sapphires. For centuries, gem traders travelled to Ratnapura, the “City of Gems,” to buy stones pulled from the earth and polished by hand.

Traditional gem cutting itself requires careful patience and fabulous eyesight.

Today, you can visit gem museums in Kandy or small-scale workshops near Ratnapura, where artisans continue to practise their craft. Look for sellers who prioritise ethical sourcing, avoiding the environmental and labour concerns linked to mass mining.

Sampath Gems comes recommended.

Feel the Beat

Various types of drums feature throughout the island’s history and in folk dances.

Traditional drums like the Geta Beraya (used in Kandyan dance) and the Yak Beraya (used in healing rituals) are crafted by hand from jackfruit wood and animal hide.

Near Matale, you can meet families who have passed down the skill of drum-making for generations. Not only are drums tuned to perfection but they are also spiritually “awakened” before use in temples and performances.

Just don’t blame me if they turn out not to be a popular gift for parents of young children, that’s all…

Food as a Traditional Art

To understand Sri Lankan culture, you need to taste it – and just as importantly, watch it being made. The island’s cuisine is an artform in itself, drawing on Ayurvedic principles, regional influences, and a long history of spice cultivation.

And it looks so beautiful, a perfectly matched palette for nearly every meal.

From delicate hoppers (bowl-shaped fermented pancakes) to slow-simmered curries ground with a mortar and pestle, traditional cooking techniques work just as well today as they ever have.

I absolutely loved the cooking class we took as part of the Hiriwadunna traditional village experience so expect to hear more about that soon.

Consider yourself a foodie? Don’t miss our guide to the dishes you cannot miss in southern India.

The Workshop Question: Who Really Benefits?

Arts and crafts workshops have become a staple of cultural tourism across Sri Lanka. On paper, they sound brilliant. They are great places to catch a glimpse into traditional life, a chance to “meet the maker,” and to take home a more meaningful souvenir than mass-produced fridge magnets. But as with many things in travel, the reality is more complex.

At their best, these workshops can be empowering. They provide artisans, often from rural or historically marginalised communities, with direct access to income, independence, education and recognition, as well as preserving the skill itself.

But at their worst, these same workshops can veer into performance, designed more to satisfy the expectations of tourists than to reflect the actual work or lives of the craftspeople. In some places, workshops have been set up not by artisans themselves but by outsiders who employ artists at low wages while marketing the experience at a premium. The result: an uncomfortable blend of cultural extraction and exploitation.

There’s also the smaller risk of freezing living traditions into something static, where crafts must appear “authentic” to outside eyes, even if those forms have naturally evolved. An artist using a new tool or exploring a different motif might be penalised for straying from what the tourist expects. And does anyone benefit when this happens?

So how can we, as responsible travellers, navigate this minefield? In truth, I wish I had a simple answer for you but it can be extremely difficult to untangle, especially when you are supposed to be on holiday.

In general:

- Ask who owns the workshop. Is it run by the artisan or a collective that fairly distributes profits?

- Look for transparency. Good places will openly discuss pricing, process, and the people involved.

- Observe how the experience is structured. Does it feel participatory and respectful, or more like a conveyor belt or zoo?

- Support long-term initiatives. Programmes led by NGOs or women’s cooperatives often prioritise community over profit. Although, not always…

Above all, remember that your presence makes an impact, whether you want it to or not.

The crafts of Sri Lanka can be livelihoods, expressions of identity, and acts of memory – and the best hands-on workshops respect that. Ideally, we’re looking for places that value the creator as much as the creation.

For more on sustainable tourism, see this article on the benefits of sustainable travel and our round-up of the ultimate ethical travel destinations.

More on South Asia