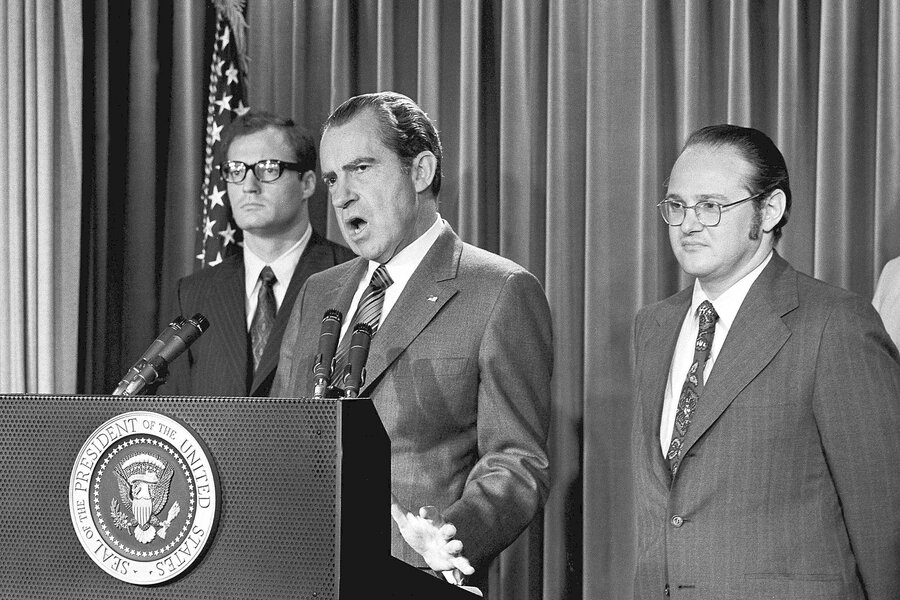

On a June day in 1971, President Richard Nixon stood behind a podium by an American flag and declared drug abuse to be the United States’ “public enemy No. 1.”

“In order to fight and defeat this enemy, it is necessary to wage a new all-out offensive,” Mr. Nixon announced. “This will be a worldwide offensive dealing with the problems of sources of supply.”

The U.S. war on drugs, launched during that speech, has endured through Republican and Democratic administrations for more than five decades.

Why We Wrote This

Richard Nixon’s “war on drugs” has always entailed a degree of U.S. pressure on foreign allies. But the Trump administration’s strikes on suspected drug-smuggling boats off Venezuela charts a new course of noncooperation.

President Donald Trump has opened the most recent chapter in that war, ordering military strikes against boats suspected of smuggling drugs from South America, and dispatching the USS Gerald R. Ford aircraft carrier to a position near the Venezuelan coast.

But one traditional element of U.S. drug policy has been missing from Mr. Trump’s actions: international cooperation.

Historically, Washington has carried out almost all its drug-war operations in Latin America with buy-in from regional governments. Whether they involved Colombian or Mexican forces tracking down a kingpin with an assist from U.S. intelligence and training, or U.S. aid packages to pay for local government action, a long line of American officials have considered this war possible only with foreign governments’ involvement.

“Most of the time, throughout the history of the drug war, the U.S. has sought to cooperate with Latin American governments to get them to reduce production or reduce trafficking through their national territories,” says Renata Keller, an expert on drug and security policies in Latin America at the University of Nevada, Reno.

“Some of it has been somewhat coercive,” she adds, “but it always has been under the guise of a cooperative effort.”

This month, both Britain, which has a handful of territories in the Caribbean, and Colombia announced that they had suspended some intelligence-sharing with Washington because of U.S. strikes against small boats thought to be smuggling drugs.

If the U.S. were to resort to military action within Venezuela’s borders, Dr. Keller says it would be clear that “we’re not seeking to cooperate anymore in the war on drugs, and it would almost certainly provoke a backlash” in the region.

A new rupture

In Colombia, cooperation is already unraveling. For the first time since 1997, the U.S. administration declared in September that Colombia was falling short in the war on drugs, and started the process to decertify Bogotá as a drug-control partner. That move, finalized last month, will deny Colombia more than $100 million per year in funds used to fight drug trafficking and insecurity, according to calculations by Michael Weintraub, director of the Center for the Study of Security and Drugs at the Universidad de los Andes in Bogotá.

“If you’re the United States, you definitely want Colombian cooperation” in fighting drug trafficking, says Dr. Weintraub, because Colombia produces about 70% of the world’s cocaine.

Successive Colombian governments have been in “lockstep” with U.S. administrations for the past 40 years, says Dr. Weintraub. Now, the Trump administration has changed the rulebook. “The uncertainty over international cooperation has increased dramatically,” he says.

One of the few examples of the U.S. going it alone in the drug war was its 1989 operation in Panama to remove then-President Manuel Noriega, a known drug trafficker. But, despite his surrender to U.S. forces, dozens of people were killed and it made little difference in drug-trafficking operations into the United States. It also served as something of a turning point for direct U.S. meddling in the region.

For decades, U.S. officials have intercepted suspected drug-trafficking boats in Latin American and Caribbean waters, seizing drugs, detaining suspects, and frequently prosecuting them. But never before have they blown them out of the water as military targets.

Since Sept. 2, U.S. forces have conducted an estimated 21 boat strikes in international waters, killing more than 80 people. Officials in Washington said the boats were carrying drugs and posed a direct threat to national security, but they have provided no evidence to support these claims.

Latin American views of the Trump administration’s actions are mixed.

In Ecuador, voters in a referendum on Sunday turned down a government proposal to base foreign troops in the country – troops who could help combat the rise of transnational organized crime there. The referendum result was seen as a sign of public mistrust for U.S. intentions in the region.

Others have backed the Trump administration’s boat strikes and its hostile statements seemingly aimed at weakening Venezuela’s authoritarian leader, Nicolás Maduro. The Venezuelan opposition leader and recent Nobel Peace Prize winner, María Corina Machado, told Bloomberg last month that any deaths from boat strikes should be blamed on Mr. Maduro.

The U.S. and Venezuela have been at odds for decades, says Dr. Keller. “But, I think a respect for nonintervention and self-determination has restrained other recent U.S. leaders from directly attacking Venezuela or its people.”

The State Department is expected to soon designate a Venezuelan drug operation, the “Cartel de los Soles,” which Washington claims is led by Mr. Maduro, as a foreign terrorist organization. That would mark the 12th Latin American drug cartel so designated since Mr. Trump took office; some analysts believe it could pave the way for direct U.S. strikes against illegal organizations outside U.S. territory.

Closer to home

So far, more than half of the cartels categorized as terrorist groups in the region are based in Mexico.

“A lot of people are extremely worried that direct, armed attacks against cartels inside Mexico could be the next step after Venezuela,” says David Saucedo, a Mexican security analyst.

Between 2008 and 2021, the U.S. funneled some $3 billion through the Mérida Initiative into Mexico and Central America, to fund cooperative counternarcotics and border security programs. The plan did not reduce drug trafficking from Mexico or arms trafficking from the U.S., but, as former U.S. ambassador to Mexico Roberta Jacobson said in 2021, it created “a culture of security cooperation between Mexico and the United States.”

Washington has threatened economic sanctions in a bid to encourage the Mexican government to adopt a stricter approach to fentanyl production and trafficking. Sanctions are just one form of U.S. economic pressure: Last December, one week after Mr. Trump threatened 25% tariffs on the country’s exports, Mexican soldiers and marines discovered more than a ton of fentanyl pills, a record seizure.

Mr. Saucedo does not expect U.S. military action on Mexican territory, in large part because “Mr. Trump’s strategy in Mexico is working for him.”