When Tomie dePaola died, he left behind a world of loss.

When Tomie dePaola’s dog, Brontë, died, Brontë left behind a grieving Tomie.

And, so, when Tomie died, he also left behind a manuscript, spare and simple, about loss–but also about memories.

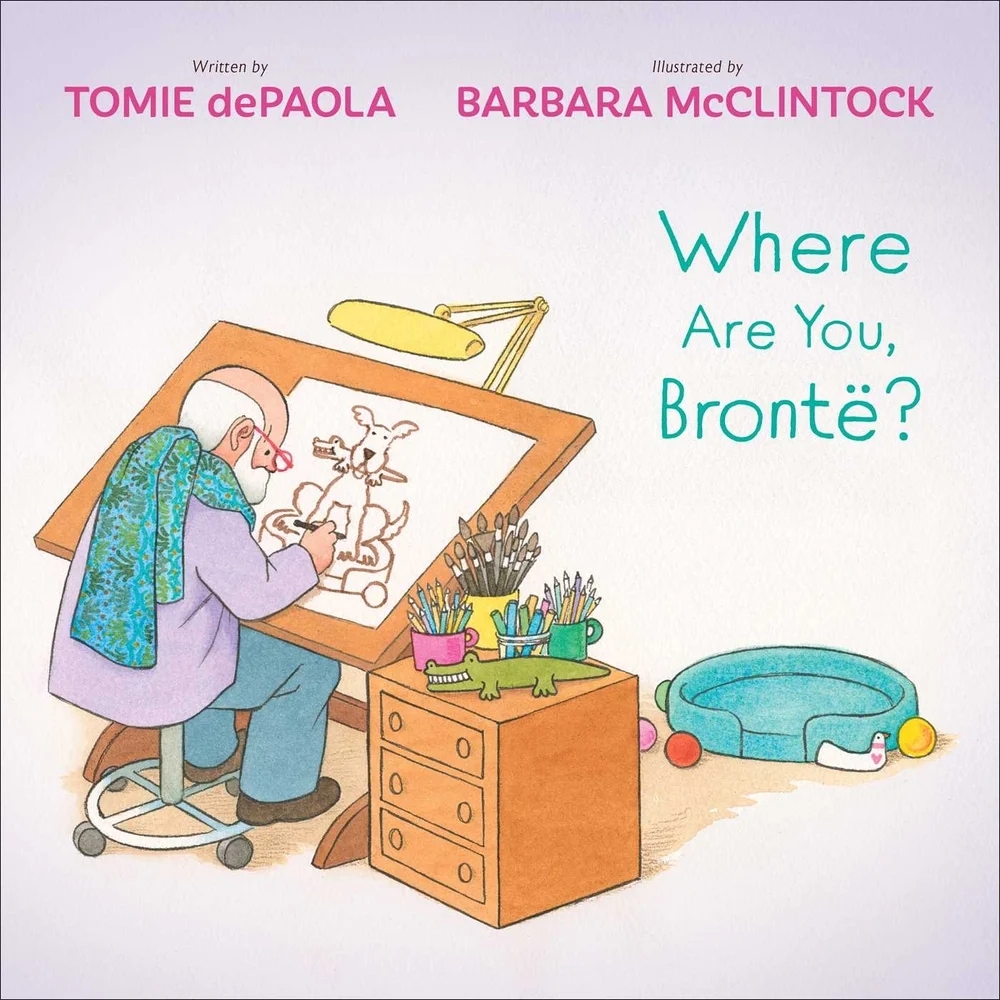

That manuscript was sent to Barbara McClintock, one of the finest artists of our days, to be illustrated and released posthumously: Where Are You, Brontë? by Tomie dePaola and Barbara McClintock (pre-order at that link and you can get a copy signed by Barbara). Given that it deals with Tomie’s death and bereavement, losing his beloved dog, the manuscript naturally carries a lot of extra feeling in our own bereavement– the loss of a beloved author, illustrator, and human being. (Frankly, I’m struck with a panoply of feelings that have nothing to do with the beautiful outcome: I’m relieved here. The book had the potential to be turned into a soppy, tear-jerky mess of fluff that would probably have made Tomie dePaola gag. In Barbara’s hands, we are safe: we have every nuance of honest sentiment and no false sentimentality.)

Loss is a funny beast. It feels physical, like a real yank of something integral away from you. No matter how intact your body may be, it feels less. A family friend recently died, and with it came a wash of memories: some about other friends lost, others about visits with my friend and his family, others about times that may have been technically unrelated but felt emotionally linked. I found myself making crème caramel for a reason that was not exactly related, as such, but kind of was. Anyway, it resulted in crème caramel, so it’s not like I’m going to complain about that. Memories go with loss. Jews sit shiva after a death, a seven day period of gathering around the bereaved and listening and sharing stories. Many cultures and faiths have memorials, funerals, and other customs involving sharing memories and stories– consider vigils and wakes, for example.

These memories feel tangible. They are an evocation of a person’s presence. It’s almost like the gap of physical loss is filled, something like a phantom limb in our spirits, until our minds are reconciled to the absence.

On every page of Where Are You, Brontë?, Tomie dePaola is present, and usually Brontë is, too. The book is incredibly simple. The repeated question, “Where are you, Brontë?” is asked, section by section, with a few lines of text building up to an overall answer. The early spreads show Brontë’s arrival, and how he settles in, sleeping with Tomie, playing with toys but never destroying them, and working his way into Tomie’s books. As time goes on, Brontë becomes an adult, and then an old, blind dog, but maintains his joyful spirit until the end, when he has lived every day of his life and is now gone; and, of course, Tomie is sad. We see him looking at the dog bed with only a toy and no Brontë. The food and water bowls, empty, with no Brontë. Having breakfast at the kitchen table, and no Brontë around, only an empty collar. Those two spreads are the only ones with no Brontë, but they sting, keenly. There’s a page turn, then, and we see Tomie on a solo walk, his face lighting up as he sees a rainbow and his eyes catch Brontë in the clouds, and all those memories from all the way through the book flood back to the reader’s mind (or at least they did to my mind) in that moment: “But then I knew you were right here.” Another page turn: Tomie draws beautiful Brontë, whose memory endures. As, of course, each adult and aware reader knows, Tomie’s memory endures in his own books, from the earliest to this one.

And that’s when the children’s librarian I showed my review copy to rushed out of her office with puffy eyes and said, “Oh my goodness this book needs to come with a YOU WILL CRY warning!” (Sorry!!! I really thought you knew the backstory of this book, or I would have warned you!)

Now, here’s the hard part: Barbara’s job wasn’t to reflect that rich layering of death, memory, and endurance, of both the dog and Tomie himself. It was to illustrate a very, very simply written book for children left by an author whose style was well known to be deceptively simple. The effect of how she did this was layered, rich, and covered a gamut from the beautifully simple picture book all the way to provoking tears in children’s book lovers in their library offices. But the actual, real task was to do a good job of illustrating a simple manuscript, and that must have been absolutely agonizingly difficult. And Barbara aced it.

I can tell you how I know she aced it. I read the book to my very convenient 4-year-old on hand, my Spriggan, and he loved the book (and kindly comforted his sniffly mother at the end). He wasn’t in the least distraught because it was such a nice book! We enjoyed it together very much, as every book to be read aloud should be enjoyed, of course. That is the goal, for the adult and child reader to enjoy the book together, but each in their own ways. In this case, that job was a really tall order because of the demands presented: a) illustrate a simple book with simple art, b) for a child, and the child will only have the context of the book itself, c) for the adult reader, who will have a lot more context about the author, and expectations to go with it.

You see, Tomie dePaola’s illustration style was described as folksy and simple. What that means, from everything I’ve read, and I recall a particularly colourful anecdote from Trina Schart Hyman describing an attempt she once made and certain colourful language she deployed along with crumpled pieces of paper being tossed around, is that it’s torturously difficult to replicate. When I close my eyes and call to mind Barbara McClintock’s art, I always see delicate flowing lines (think of another “where” book she illustrated, Adèle & Simon) that are more closely akin to Trina Schart Hyman’s than to the simple, broad lines of Tomie’s Strega Nona.

Simon’s drawing of a cat is very good. I think Brontë would like it, and Tomie would, too.

So, choosing Barbara with her lovely lines and keen eye for children for this job was absolutely genius. She would take the job seriously, reverently, even. Her respect for Tomie dePaola is total, and that means that her respect for the picture book (also demonstrated over a long career of brilliant books) is also total. She would have her own expectations, but ignore the expectations of adult readers when they competed with the all-important child; by doing so, she would take that manuscript and make a beautiful book. And so her art brings the words to the book to life not as Tomie dePaola would have done it, but as Tomie as a character in his own book of life, illustrated by Barbara McClintock. Barbara as illustrator and artist, who loves picture books by people like Tomie, knows when art is active and when art is illustrative. She imbibes elements of his style in grateful and graceful homage, but does it in her own way, with the breath of life only an artist doing her own work can do. There’s a little mouse I’ll let you find who appears in her wispy fine lines, simple but perfect, popping up in the broad folksy grasses, evoking a curious Barbara exploring a world of Tomie’s making. I can tell, on every page, that she worked with love, awe, and enjoyment.

And I read it, snuggled in bed with my own tiny boy, and we read it with love, awe, and enormous enjoyment– and, in my case, with damp eyes and a sniffly nose. I got patted on the head and given a hug and a kiss. It was fine– better than fine. I hope you’ll enjoy it, too.

It’s a bit like falling into a picture book world, thinking about all we’ve gained from all of these creators over all of these decades.