Unsurprisingly, József Gémes’ The Princess and the Goblin (1991), an animated co-production between Hungary, Wales, and Japan, appears to be a forgotten film. Produced and circulated during the Disney renaissance of the late 1980s and early 1990s, its comparative obscurity can be (speculatively) attributed to its release during a time when western animation, especially in the United States, was characterized by polished animation, celebrity voice actors, and elaborate multimedia marketing strategies. While The Princess and the Goblin followed the trend at the time of major animated films adapting notable fairy tales (in this case, George MacDonald’s 1872 novel The Princess and the Goblin), the obvious lack of those three aforementioned characteristics strikes me as a potential reason why the film never gained much traction. Indeed, film critics in the US were largely unimpressed with the quality of the animation (Beck, 213). The film did, however, achieve support from family-oriented entertainment advocacy groups in the US. Given the lack of written work on the production, circulation, and reception of The Princess and the Goblin, I will attempt a brief, speculative discussion of the film’s reception, specifically focusing on its US reception and its approval by some of these Christian and US conservative groups (notably the Dove Foundation and the Film Advisory Board)

The few scholarly interventions into The Princess and the Goblin, in addition to some primary sources, describe the film’s transnational status as a co-production primarily between Hungary and Wales. The film, directed by the Hungarian animator Gémes, was produced in Wales “with a substantial $10 million budget” and was subsequently picked up for theatrical distribution in the US by the Hemdale Film Corporation in 1994 (LaPlue, 74). The film was poorly received critically and financially. Caroline LaPlue writes that film critics eviscerated the film over its poor animation and “uninvolving story” (75). Audiences also did not care for the film; it was a box office failure, grossing only $2.1 million at the US box office (for historical purposes, it is worth noting that Disney’s The Lion King, was also released in 1994). LaPlue’s argument suggests that a combination of negative reviews, poor animation and sound design contributed to the film’s financial failure in the US. I would add a few additional reasons for the failure of The Princess and the Goblin to broadly connect with American audiences: its circulation via an independent film company not known for animated films and the lack of notable celebrity names in the cast. The voice cast of the film consists primarily of notable English and Welsh actors: Rik Mayall, Claire Bloom, Joss Ackland, and Roy Kinnear; none of whom would as recognizable to American audiences as Robin Williams’ performance as Genie in Disney’s Aladdin (1992) or James Stewart’s presence in Universal’s An American Tale: Fievel Goes West (1991).

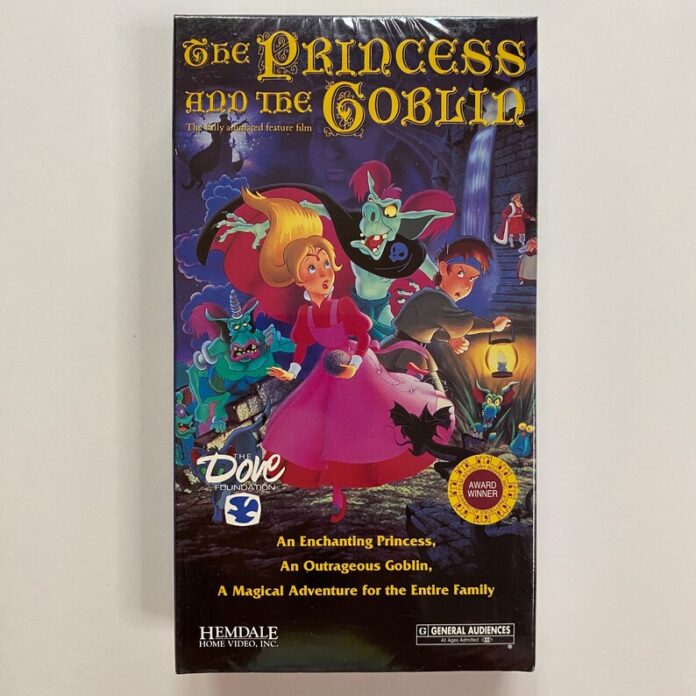

While film critics and popular audiences were clearly not interested, The Princess and the Goblin piqued the interest of some family-focused entertainment advocacy groups in the United States. Jerry Beck’s Animated Movie Guide, one of the few primary sources to touch (albeit briefly) on this reception summarizes: “This motion picture was the winner of the Film Advisory Board’s Award of Excellence [and] the Dove Seal of Approval from the Dove Foundation Review Board” (214). For the film’s home video distribution, both the Dove Seal of Approval and the FAB’s Award of Excellence are featured prominently on the VHS cover. Dove is a Christian non-profit advocacy group focusing on children’s entertainment that reviews films through an evangelical lens. Founded in 1991, the organization has published numerous reports, including on the profitability of G-rated films (Candeub, 911) and, according to its website, has had notable partnerships with McDonalds’ Ronald McDonald Children’s Charities and Twentieth Century Fox Home Entertainment. Despite receiving the organization’s “All Ages Dove Approved” stamp, Dove reviewers suggested that some of the darker imagery may be unsuitable for younger children. The Film Advisory Board’s mission is less clear, though it is similarly concerned with family-oriented entertainment. No review of The Princess and the Goblin currently exists on the FAB’s website, making it difficult to ascertain how precisely it achieved the organization’s Award of Excellence.

Fig. 1. A VHS copy of The Princess and the Goblin featuring the Dove Foundation’s Seal of Approval and the Film Advisory Board’s Award of Excellence. OddOwlMedia.

These two “awards” are not especially interesting or insightful towards understanding The Princess and the Goblin as a film. Rather, it seems that these acknowledgements of ‘family friendliness’ constitute a marketing strategy towards US audiences seeking alternative family entertainment to Disney. Jerry Beck notes that, in the aftermath of its less-than-stellar critical evaluation and box office totals, “The U.S. distributor, Hemdale, so desperate for some good reviews, used quotes in its newspaper ads from the children of noted movie critics” (Beck, 213). Coinciding with this strategy, the prominent display of these two seals of approval on the film’s VHS cover and other promotional material was likely targeted towards conservative Evangelical families. Indeed, since major studios such as Disney or Universal would not have to rely on such marketing strategies, I propose that explorations of underacknowledged animated films–especially those not produced within the US–during this era may find these particular “seals of approval” as novel starting points.

References

Beck, Jerry. The Animated Movie Guide. A Capella Books, 2005.

Candeub, Adam. “Creating a More Child-Friendly Broadcast Media,” Michigan State Law Review, 2005, 911-929.

LaPlue, Caroline. “Seldom Like Yesterday: Situating the Novel and Film Adaptation of The Princess and the Goblin,” Scientia et Humanitas: A Journal of Student Research, 2023, 70-84.

Filmography

Aladdin. Directed by John Musker and Ron Clements, Walt Disney Pictures. 1992.

American Tail, An: Fievel Goes West. Directed by Phil Nibbelink and Simon Wells, Universal Pictures, 1991.

Lion King, The. Directed by Roger Allers and Rob Minkoff, Walt Disney Pictures, 1994.

Princess and the Goblin, The. Directed by József Gémes, Hemdale Film Distributors, 1991.

Mark Barber is a Toronto-based teacher and scholar. He is a PhD candidate in Film and Moving Image Studies at Concordia University, Montreal. His work specializes in cultural policy analysis, cultural institutions, queer studies, and North American right-wing media cultures.