Article begins

“I mean, why should I have to want to kill myself in order to transition?”

I had known Max for almost an hour before this blunt statement hit me in the chest.

We were attending a conference session discussing the diagnosis of ‘gender dysphoria,’ led by a local nonbinary psychotherapist. The presentation offered a largely quantitative analysis: incidence rates of the gender dysphoria diagnosis in the general population, co-occurrent diagnoses like anxiety and depression, and the percentage of patients with a gender dysphoria diagnosis who receive interventions like hormone-replacement therapy (HRT) and surgeries. After being bombarded with statistics and best practices, Max asked the speaker, “Do you believe that the diagnosis of gender dysphoria can be harmful?” The speaker described a wide array of possible experiences, finally concluding: it depends.

Mental health diagnoses can relay the depth of struggles that individuals undergo while also providing people with hope that this state of distress shall pass. Yet, many people describe how receiving a diagnosis of gender dysphoria often involves contorting oneself into a legible form of personhood that the provider can diagnose: that of a suffering patient. In my research, I use the term “trans service users” to describe transgender people seeking gender affirming care who enter mental health clinics and confront the decision of whether to inhabit the role of “patient.” What Max articulated so succinctly in their question was the way the data presented seems disjointed from the real-world harms and dynamic experiences of being trans. Existing as trans in the current political climate causes many trans people to experience anxiety or depression, as they anticipate potential violence in day-to-day encounters. Yet, Max and I both agreed that while diagnostic processes are deeply complicated, the social script of gender dysphoria as a diagnosis can also manifest as a seeming fixity of the category “trans.” In order to be trans enough for further services, one must be actively and regularly dysphoric, along with all of the connotations of the diagnosis.

In this space, fixity and fluidity collide in two major forms. First, a fluid portrayal of one’s gender identity and personhood conflicts with the rigidity of criteria for the diagnosis, creating a struggle for agency in the therapeutic process. Second, trans users deploy methods of semiotic fluidity to contest this restriction in the diagnostic process, using indexical signs to portray themselves to providers as the legible figure of the “trans patient.” Max’s statements demand consideration of deeper questions: What are the risks of creating a mental health diagnosis like gender dysphoria, with all the local meanings that accompany that diagnosis, for trans people receiving mental health services? What work does the association between transness and mental health diagnosis do in the discursive portrayal of what it means to be transgender? Fluidity, both in experiences of gender identity and personhood as well as in semiotic practices, presents a useful analytical framework to explore these questions.

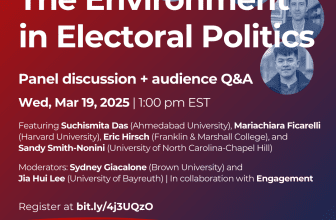

A logo used to note a “safe space”, a space where individuals can feel free to perform their identity in any way they would like, for any and all LGBTQ+ identified people. Originally developed for use at a rural school, many have used images like the above to mark spaces and people who are LGBTQ+ identified or allied.

Credit:

Annie Lanning

The 2018 Progress Pride Flag in a heart, surrounded by the words “Safe space, all are welcome here.”

Historically, transness and gender nonconformity have been intensely scrutinized by the state and its proxies, and trans individuals themselves have long faced the threat of institutionalization. Service providers have attempted to separate themselves from this carceral history, as mental health care has evolved through the slow elimination of pathologizing diagnoses—namely “transsexualism” and “gender identity disorder” in the DSM-III and DSM-IV respectively. Yet, this history persists in the minds of many American trans service users—and, crucially, service providers. In my research, trans service users report mental health care serves as a prerequisite for other services, as many gender-affirming care providers still require a letter of testimony from a mental health provider, despite the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) guidelines that advocate against doing so. Many trans service users, including Max, approach mental health care from a place of deep ambivalence, concerned for the ways that their words, bodies, and actions might be interpolated into a diagnostic framework.

The concept of the “listening subject,” originally coined by Miyako Inoue, offers a lens to explore such interpolation. Linguists and linguistic anthropologists have long documented how meaning in speech is not solely the possession of the speaker. Literature on the listening subject articulates how the identities of speakers impact how their speech is interpreted, which illustrates how beliefs and stereotypes about speakers can overdetermine interpretations of the content of their speech. Importantly for my context, the diagnostic categories seem to color the words that service users speak, the connotations of which can either enable or preclude their access to services.

I have been thinking about the contentious dynamic between mental health service users and providers as predicated on addressing a “psychotherapeutic listening subject.” If the DSM-5 diagnosis of gender dysphoria is, to paraphrase Hil Malatino, an individualized and institutionalized experience of “being trans and feeling bad,” psychiatrists and psychotherapists function as the arbiters of both what “feeling bad” can mean and what constitutes “bad enough” for diagnosis. In describing how providers make these decisions, scholars document the importance of a provider’s “feel” or “spidey-sense” for particular diagnoses. Clinicians must compile the various evidence of distress and feelings of transness presented in the session—through bodily comportment, linguistic tendencies, descriptions of life events, anything that induces a sort of “feel”—to make their diagnosis, which enables further services. However, the need to align with previous conceptions of the diagnosis can cause the process to feel baseless and unjust for service users.

This transformation of fluid and dynamic personhood to a seemingly fixed diagnosis is the subject of ire among many trans and gender-nonconforming service users. Many people desire swift access to services but are oftentimes met with providers who seem unwilling to provide access to the services they seek. If these users present a truthful account of their complex relation to gender, they may not be seen as “dysphoric enough” to access urgent intervention. These service users, through various online forums like Reddit, Discord, and Tumblr, often discuss their clinic experiences with other trans people. What becomes distilled in these online spaces is a simple tactic: portray yourself in a way that creates a sense of urgency without creating a dire scenario. Just enough, but not too much.

This script has become commonly embraced by many of my research collaborators, as service users cite small acts of signification to portray themselves as an ideal type of trans patient, acts that I describe as producing semiotic fluidity. Some service users intentionally raise their scores on depression and anxiety screeners from mild to moderate levels, so they consistently get flagged during appointments; others stretch depressive episodes longer when disclosing symptoms to providers. This fluidity also produces forms of erasure, limiting what service users believe they can discuss with providers. Discussions of active thoughts of suicide risk hospitalization and further delay of services, which means that service users often portray urgency through less risky means. Others sequester various questions and concerns about complex gender presentation, portraying their transition within the medical framework of MTF (male-to-female) or FTM (female-to-male). These strategies are not acts of deception, but rather legibility. Many of the service users regularly feel distress and dismay, and the providers who view their services as gender-affirming understand the feelings of distrust that run rife through medical institutions. Most important for this discussion is the notion that on a session-to-session, moment-to-moment basis, these strategies both push and hedge severity and urgency, to create a legible clinical persona that will be eligible for intervention sooner rather than later.

It is not necessarily novel to argue that service users may withhold specific information from their providers to conform to a preexisting script of care. Importantly, this process is vital to many trans service users as they navigate mental health systems and health systems more broadly. I view this use of semiotic fluidity of social persona through what Barrett and Hall call “indexical misrecognition.” Deployed by a speaker, especially of a marginalized status, misrecognition can become a specific discursive strategy for preserving a speaker’s safety. In a clinical context, misrecognition may become vital for trans service users as they attempt to portray a legible social persona, one with latent thoughts of suicide that are never acted upon, a type who believes binary transition would be the answer to their embodied experiences of dysphoria and malaise.

The trade-off for many trans service users is whether to be legible as treatable with further procedures that could be expedited, while also misrecognized; or to offer a nuanced depiction of their gender, enabling themselves to be recognized more transparently but be illegible as a trans person requiring services. To be misrecognized enables access to care, which many trans people view as a small price to pay.

For trans service users, the script of the ideal trans patient with gender dysphoria exists as a semiotic resource to be used when expedient. However, not all service users are willing or able to concede to this self-representation. In their discussion of transition, Max told me that they didn’t experience many depressive, anxious, or dysphoric thoughts around their gender identity. Rather, they felt that their gender performance was an exploration, and, as a result, they could not inhabit the legibly trans patient script. The potential conflation between pathologized mental health diagnoses and transness creates deep discomfort for many service users and, further, can have ramifications for which types of people count as “being trans,” with or without HRT or other forms of gender-affirming care. These scripts are semiotic modalities of gate-keeping, determining what it might mean to be “trans enough.” For Max, it took time to arrive at their current comfort with a gender-in-flux. Yet the script of trans precarity continues to profoundly impact both service users and providers, coloring access and lack of access for service users.

Both mental health providers and users are currently stuck in a hostile situation, as state and federal governments further curtail access to services in the United States. For many trans people, mental health care is the only realistic form of gender-affirming care to which they have access. Providers, who increasingly identify as trans, queer, nonbinary, or queer-allied, are navigating that same system alongside their service users. Increasingly, many of the service providers I spoke with are engaging in clinical practice and advocacy work through petitions or protest. Though the future remains uncertain for nationwide access to HRT and further surgeries, many service users and providers still manage to forge meaningful therapeutic relationships in the face of systemic distrust and violence. These providers-turned-advocates may be able to create an experience of care that enables the recognition of fluid multiplicity while avoiding the pitfalls of diagnostic fixity—care that trans people may finally experience as caring.

Sarah Muir and Courtney Handman are the section contributing editors for the Society for Linguistic Anthropology.

For articles on related topics from the Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, see:

Signs in Conflict: Contrastive Indexical Meanings of the Star of David in a Queer Ban of the Jewish Pride Flag by Katherine Arnold-Murray

From Sissy to Sickening: The Indexical Landscape of /s/ in SoMa, San Francisco by Jeremy Calder

“And It Just Becomes Queer Slang”: Race, Linguistic Innovation, and Appropriation within Trans Communities in the U.S. South” by Archie Crowley

Understanding Movement and Meaning in Janana Communities by Ila Nagar

Becoming Muslims with a “Queer Voice”: Indexical Disjuncture in the Talk of LGBT Members of the Progressive Muslim Community by Katrina Daly Thompson

Besides Tongzhi: Tactics for Constructing and Communicating Sexual Identities in China by Zhiqiu Benson Zhou